Research shows that accommodating clients’ preferences in therapy can lead to better therapeutic alliances, lower dropout, and improved outcomes. But how can you go about finding out what clients actually want?

‘Just ask’? It seems the obvious answer and often it is. Asking clients what they want from therapy can be the most relational, respectful, and nuanced way of finding out about their preferences. Therapists can ask clients about their preferences in lots of different areas:

The methods that they would like to use: for instance, would they find it helpful to do a short relaxation exercise at the start of each session?

The topics that they would like to talk about: for instance, do they want to focus on their past experiences, their current circumstances, or both?

The aims for the therapeutic work: for instance, do they want to change their behaviours, or come to a greater acceptance of their life?

The therapist’s style of engagement: for instance, do they want more or less challenge from the therapist?

Contracting and format issues: for instance, would they like sessions weekly or fortnightly?

Often, first sessions are the best time to start talking about these issues, and generally research show that clients do like to be involved in these kinds of decisions. However, for some clients—particularly those who have not had therapy before—it can feel overwhelming to be asked too many questions about what they want, so sensitivity and timing are essential in helping clients articulate how they would like therapy to be.

There are, however, also downsides to relying on verbal dialogue, alone, to assess clients’ preferences. First, face-to-face, clients may find it hard to be fully open about what they want from therapy, particularly if they think that the therapist may disapprove of their preferences. Second, therapists may neglect to ask questions about the preferences that are of most importance to clients.

One way of addressing this second problem is by using a relatively structured, and comprehensive, schedule for asking clients about their preferences. Barbara Vollmer and colleagues, for instance, have developed the ‘Treatment Preference Interview’, which is a semi-structure, discussion based tool that assesses clients’ preferences about the therapist, their activities, and the type of therapy to be offered (Vollmer, B. et al. [2009]. A therapy preferences interview: Empowering clients by offering choices. Psychotherapy Bulletin, 44[2], 33-37).

This kind of schedule is a great idea; but it can be pretty time consuming, and it still does not get around the problem that clients may find it difficult to say, on a face-to-face basis, what they want from therapy.

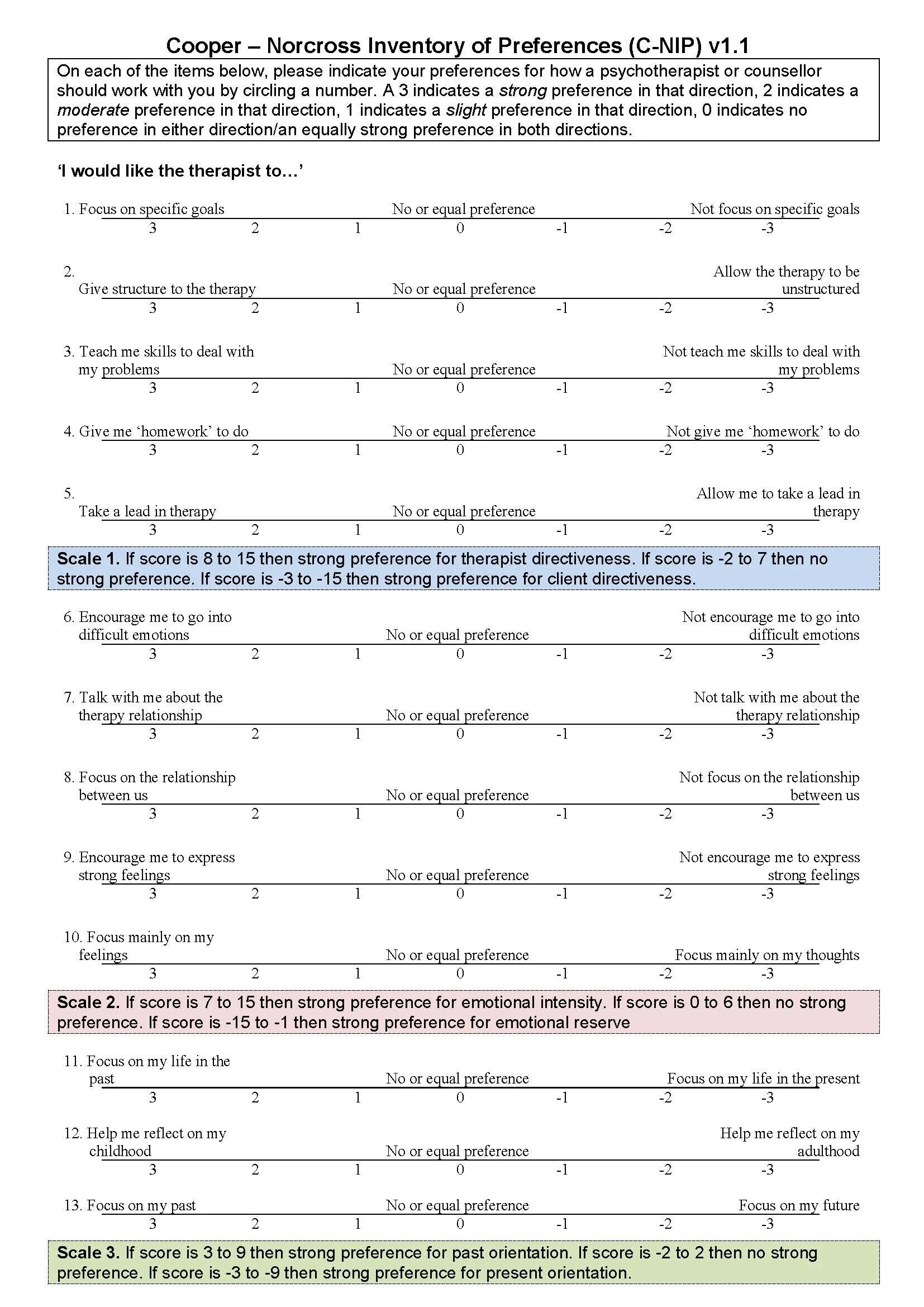

It’s for this reason that we developed a freely-available questionnaire to help stimulate discussion about what clients want from therapy: the Cooper-Norcross Inventory of Preferences (with validated translations available in German, Italian, and Serbian). The form consists of 18 items, which ask clients about the particular style of therapy that they want (see below). There are then a series of open questions asking clients about strong preferences in other areas of therapy, such as format and use of self-help materials. The 18 items are grouped into four over-arching dimensions:

Whether the client wants the therapy to be more therapist-led, or more client-led

Whether the client wants encouragement to go into strong emotions or not

Whether the client wants to focus on their past, or their present and future

Whether the client wants warm support or more focused challenge.

Clients’ responses for each dimension can be added together, so that it’s possible to see where they might have strong preferences. For instance, it may emerge that a client wants a more client-led therapy and to focus on their past, but does not have strong preferences on the other dimensions.

If you’re interested in how we developed the C-NIP, and evidence of its reliability, our original paper is here. We also conducted a very interesting comparison of therapy preferences for therapists (as clients), and laypeople, which can be found here.

Of course, it’s not a case of just giving the form to the client and then doing whatever they want. The aim of the C-NIP is to act as the basis for a dialogue, so that therapist and client can discuss in more detail the ways of working that are most suited to that individual. And, of course, the client may have preferences that the therapist cannot accommodate. For instance, a person-centred therapist may not be trained, or willing, to practice in a highly goal-oriented, directive way. But, probably, it’s better that such strong preferences are brought to the fore at the start of therapy, rather than emerging several months down the line. That way, any incompatibilities between therapist and client can be talked about and, if necessary, onward referrals can be made.

Our research shows that clients, in general, like to complete the C-NIP. They find it refreshing to be asked what they want from therapy, and appreciate the offer of different ways of engaging. A few clients, though, do find it less helpful: particularly those that are new to therapy and have no idea what it is or what they want. So, again, sensitivity and timing are needed in the use of the questionnaire. For instance, it might make more sense to introduce the C-NIP a few sessions in to therapy and, in fact, we recommend that therapists use it at review points (for instance, Session 4 and Session 10) to check how the client is experiencing therapy and whether there is anything they would like to change.

A paper version of the C-NIP measure can be accessed here, and guidelines for its use are here. We also have a website where the questionnaire can be completed online, with automatic calculations of scores on the four different dimensions. We’re currently doing further research into the C-NIP, and our online site asks if we can, anonymously, hold on to data; so if you and your client were willing to complete the questionnaire online that would be really helpful for us.

In conclusion, research into assessing, and accommodating, client preferences shows that it is a complex and nuanced area. One thing that is clear is that it’s not as simple as just asking clients what they want and doing it. Often clients don’t know, and sometimes what they want at the start of therapy is not what’s ultimately most helpful to them. Nevertheless, that doesn’t mean that asking clients about their preferences is a waste of time: clients do sometimes have strong preferences, and not talking about—or adjusting to—these can sometimes lead to poor therapeutic outcomes and dropout. So developing skills in assessing client preferences is an important area for ongoing training and development: helping us to provide each client with the particular therapy that is best suited to them.