It’s felt a pretty bruising time in the UK person-centred community of late. Recent articles in the journal Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies have critiqued our pluralistic work for being ‘erroneous and logically fallacious’ (Murphy et al., 2025); for attempting to ‘control the narrative’ (Moore, 2025); and the pluralistic framework for person-centred therapy as ‘reductionist’, ‘unnecessary and incompatible’ with the person-centred approach (Ong et al., 2019). Meanwhile, the relational depth-informed approach to therapy that we’ve tried to articulate has been described as ‘authoritarian, inconsiderate, and inconsistent’ (Sommerbeck et al., 2025); and ‘repetitive and incompatible’ with the person-centred approach (Jain & Joseph, 2024).

It hasn’t felt good, and the temptation to hit back with carefully curated academic argument has felt intense. What I keep coming back to, however, is a yearning to find a different way of responding, one which doesn’t feel like a toxically male locking of antlers: ego, ‘winning’, and the avoidance of shame. I know, for myself, how compelling that is, and how ultimately destructive it ends up being (even if it feels relieving at the time). So how do we, I, find genuinely constructive ways forward, ones that acknowledge and prize both sides? After all, if we can’t do that, if we can’t—within a person-centred, empathic, relationally-oriented community—find ways of talking to others and respecting differences across positions and perspectives, what does that say about the potential for peace, and our potential to contribute towards it in a conflict-riven world?

Is there a way, then, that we can all be right: where we’re all intelligent individuals doing our best, where all our perspectives can be of value? For me, one way into that is to try and understand more deeply the differences between the perspectives: to dig into the nuances, complexities, and actualities of what others—and, indeed, ourselves—are trying to say. It’s so easy to mischaracterise the other, oversimplify, and to project. I’m sure that’s something that I’ve done at times and I can see how unhelpful it’s been.

So I want to suggest that, perhaps, one way of understanding some differences between pluralistic and more classical takes on the person-centred approach is by contrasting, respectively, a process-oriented understanding of what it means to be person-centred with an outcome-oriented one. Of course, these distinctions aren’t either/or, and people’s understandings can have elements of both. But I think they represent two somewhat different readings of Rogers and the meaning of his work for therapy.

An outcome-oriented understanding says, ‘This is what a person-centred approach to therapy is…’ It’s Rogers’s work as product, as a formal theory of how to do therapy. For instance, it’s therapy as based on the six conditions that Rogers hypothesised as necessary and sufficient for therapeutic personality change—the most popular definition that emerged in a recent online poll of the PCA community. So, here, being person-centred is about engaging with the client in an empathic, accepting, and genuine way: it’s about listening, receiving, engaging—relating at depth with the client in a nuanced and reflective manner; it’s about going up to particular levels of ‘interventiveness’, but not beyond. This outcome-based understanding doesn’t mean that the therapist, themselves, is fixed or rigid or not adapting to the client, or not growing and evolving as a human being, but it’s about person-centred therapy being a particular thing. There’s an emphasis here on boundaries and their policing: on ensuring a non-dilution or non-contamination of the approach. And it’s a way of thinking about the PCA which can be really important to ensure the coherence of PCA as a practice—particularly, for instance, when trainees are developing as practitioners. There has to be some boundaries to the approach, some clarity about the thing itself: what PCA actually is.

Note, although an outcome-oriented approach strive to define and police the boundaries of person-centred practice, there is not one unified definition of what PCA is. In fact, there are probably numerous—and, at times, conflicting—definition of what PCA practice means. As with Wittgenstein’s ‘language games’, PCA, as outcome, is probably best considered a ‘family’ of related and overlapping understandings, with homogeneity more assumed than actually achieved.

A process-oriented understanding takes something different from Rogers. Here, the emphasis in on the PCA and the PCA community as something that is growing, evolving, and developing—in line with Rogers’s view of what it means to be fully functioning. Rogers writes, for instance, that in the fully-functioning person:

defensiveness or rigidity, tends to be replaced by an increasing openness to experience. The individual becomes more openly aware of his own feelings and attitudes as they exist in him at an organic level…. He is able to take in the evidence in a new situation, as it is, rather than distorting it to fit a pattern which he already holds…. It means that his beliefs are not rigid, that he can tolerate ambiguity. He can receive much conflicting evidence without forcing closure upon the situation. (Rogers, 1961, pp.115-6)

So, from a process-based standpoint, this is an openness to the PCA as something that is learning, changing, and evolving; that it is always striving to develop its edges and go beyond black-and-white thinking; that is ultimately unknown, plural, and heterogenous. And, from this standpoint, there’s also an emphasis on members of the PCA community relating to each other with care, valuing, and respect—to not demonise either those inside of, or out of, the person-centred field. There’s also a drawing on Rogers’s emphasis on evidence—along with experience and self-reflection. A process-oriented understanding strives to draw on research findings even if that’s emotionally hard to do and challenging our own beliefs and wants. Rogers talks about this in his own research journey: ‘in our early investigations I can well remember the anxiety of waiting to see how the findings came out. Suppose our hypotheses were dis-proved! Suppose we were mistaken in our views! Suppose our opinions were not justified!’ However, he goes on to write:

At such times, as I look back, it seems to me that I disregarded the facts as potential enemies, as possible bearers of disaster. I have perhaps been slow in coming to realize that the facts are always friendly. Every bit of evidence one can acquire, in any area, leads one that much closer to what is true. And being closer to the truth can never be a harmful or dangerous or unsatisfying thing. So while I still hate to readjust my thinking, still hate to give up old ways of perceiving and conceptualizing, yet at some deeper level I have, to a considerable degree, come to realize that these painful reorganizations are what is known as learning, and that though painful they always lead to a more satisfying because somewhat more accurate way of seeing life. (1961, p. 24)

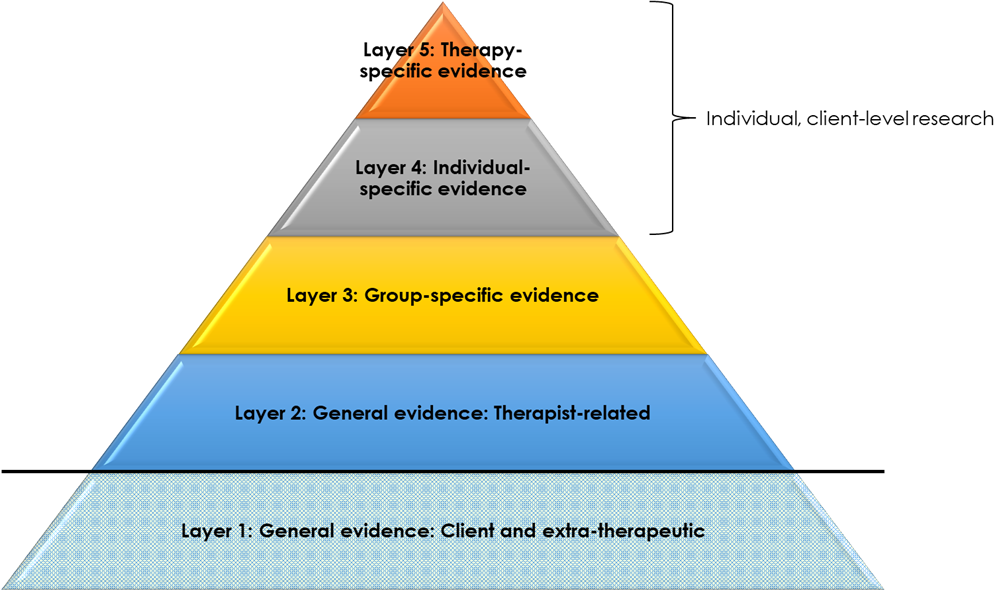

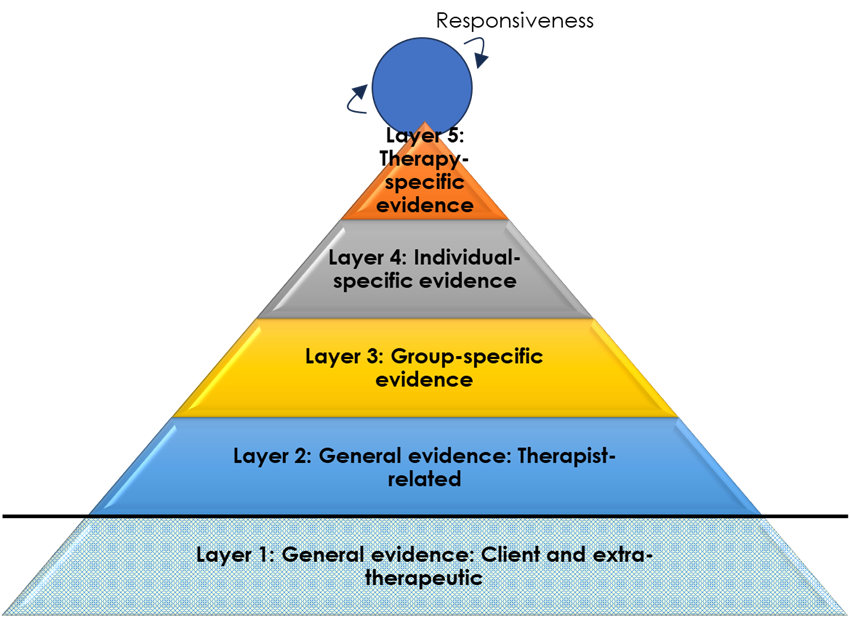

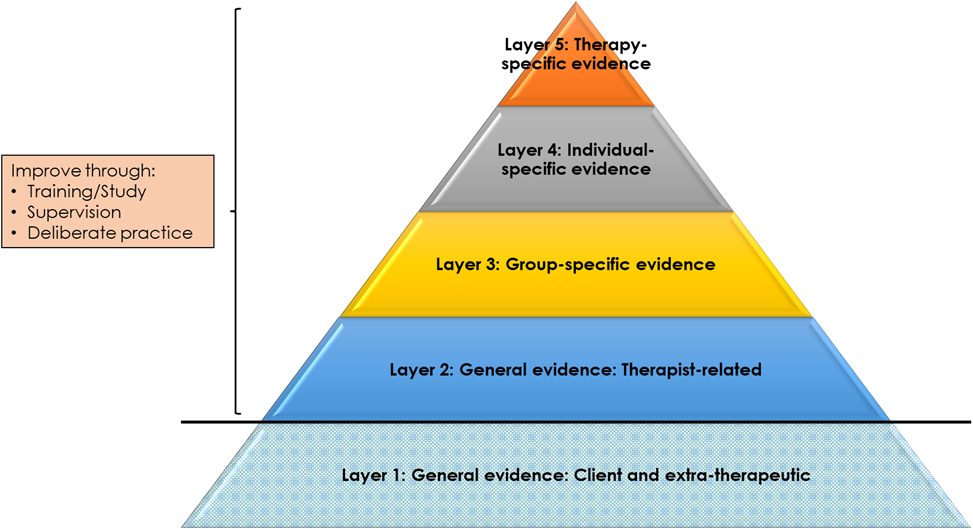

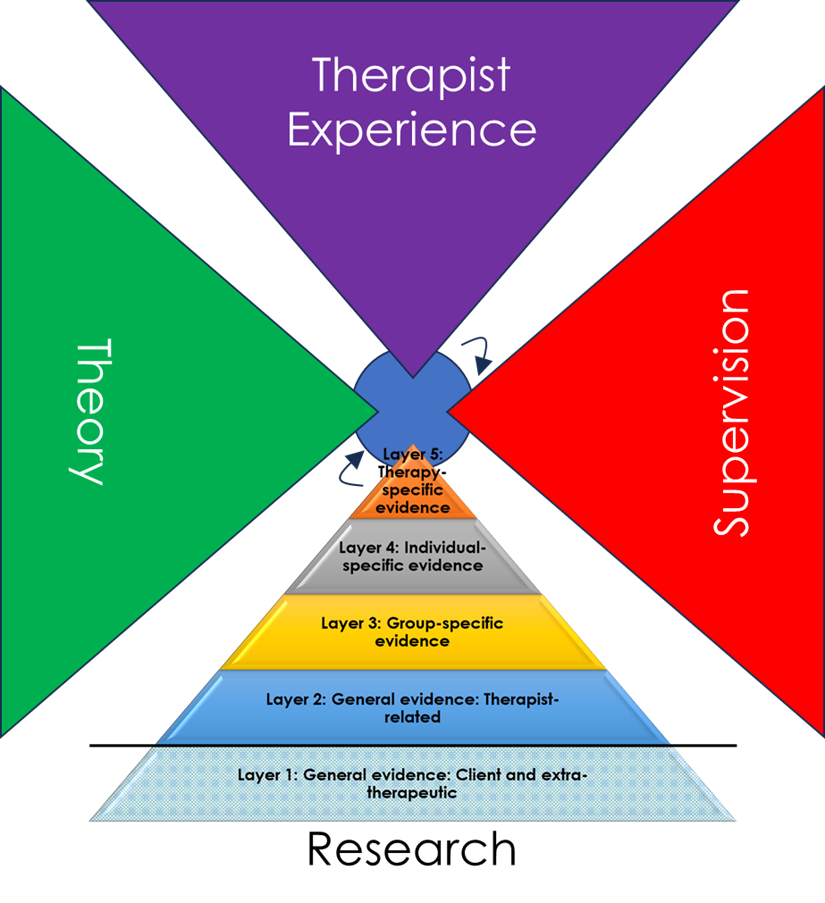

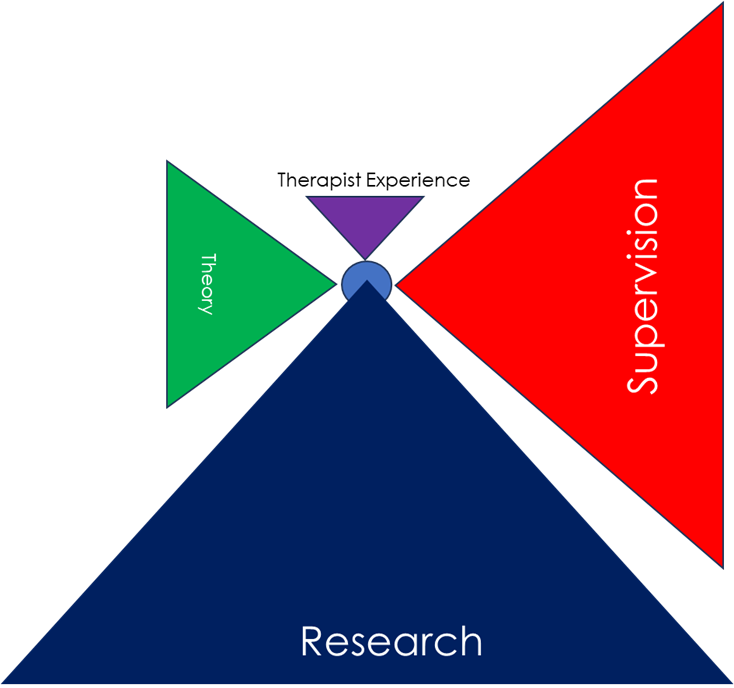

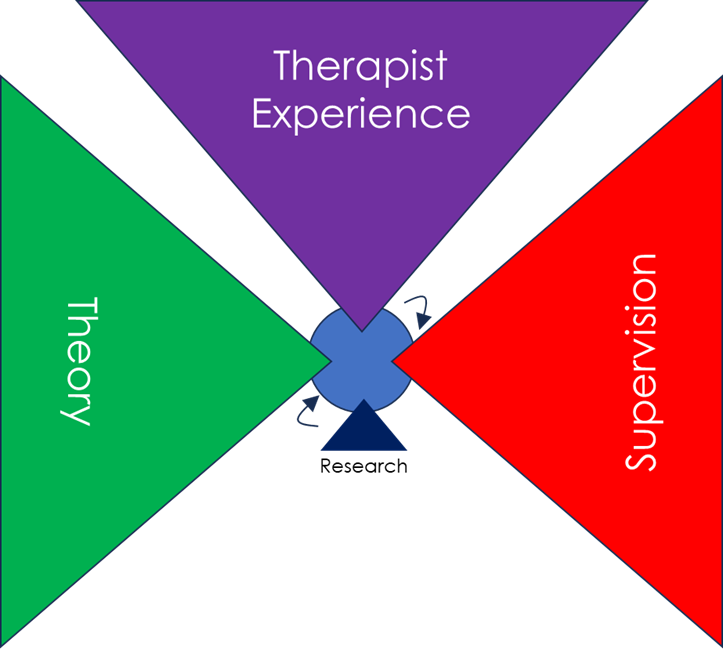

Graphics by https://xabierlopez.co.uk

Great. But what happens when those adjustments and reconceptualizations mean moving beyond the original stipulation of PCA practice? What happens when, for instance, the evidence no longer supports the theory that six core conditions are necessary and sufficient for therapeutic personality change (see blog here). From an outcome-oriented standpoint, the emphasis needs to be on the coherence of the PCA, so if the research says there’s a problem, it’s the research that must be wrong. Evidence can be discounted, minimised, ignored: there’s a multitude of ways in which any research finding can be explained away so that coherence of the approach can be maintained. From a process-oriented standpoint, on the other hand, the evidence comes first, even if it means updating and revising one’s approach. But the question is, what then remains, and is it still ‘person-centred’? From an outcome-oriented perspective, there has to be clear boundaries, and if you’re starting to reject the central tenets, then it’s time to call what you do something else.

I imagine that where we stand on these dimensions has a lot to do with how we came into the PCA and Rogers’s work. For myself, for instance, it was through reading Rogers’s On Becoming a Person as a student, and I think I have always seen this description of the fluidity and openness of being as the essence of what it means to be person-centred. By contrast, I had just a one year certificate training in person-centred therapy before four years training as an existential psychotherapist, and only after that came back to the person-centred community. So, in contrast to many others, I had much less formal induction into person-centred therapy as trained and practiced in the UK.

So I have that alliance to a more process-oriented understanding of Rogers, as I’m calling it, but I really want to argue (and push myself to argue) that both perspectives are of value. An outcome-oriented understanding keeps a coherence at points in time. A process-oriented understanding evolves and moves through time. Both grow from Rogers’s own thinking, but they are not always aligned. Chris Molyneux, in his comments on this blog (see below), uses the metaphor of a Victorian house to describe the PCA. For me, that’s a perfect description of how the PCA is seen from an outcome-oriented standpoint: something solid, constant, relatively unchanging. And, as he puts it, if you renovate that into something different, then you can’t still claim that it’s the PCA. But from a process-oriented standpoint, a more appropriate metaphor for the PCA might be a tree, or some other kind of organism, that grows, develops, evolves. Here, multiple branches can evolve from the same roots, with none more determinedly the original tree than the others. Is the PCA more like a house or a tree? Again, at least from a process-oriented standpoint, there is no right or wrong here: both perspectives can be true; both have their strengths and their limitations.

From an outcome-oriented standpoint, there’s something that can be deeply undermining about a process-oriented approach. ‘I’m trying to do therapy here… and you’re questioning and challenging and undermining and constantly threatening to shake up the foundations on which our approach is based on. You’re confusing things in unhelpful ways.’ I think that’s how, from a more classical standpoint, a pluralistic PCA can be seen: that it’s moved beyond the fundamental principles of person-centredness and it’s now threatening to drag others with it. It needs to be expunged.

And from a process-oriented understanding, there’s something that can be seen as rigid and inflexible in a more outcome-oriented understanding of PCA. There’s a frustration, a fixidity… ‘Why aren’t you open to learning and developing and growing in an infinite, unpredictable variety of ways?’ And that calling can be very frustrating to those who are just trying to get on with their practice: who want something solid on which to define their work, and who don’t want to be redefining and reorganising their sense of therapist identity. Moreover, perhaps that urgency to grow and evolve can lead to a tendency to over-perceive, or over-emphasise, rigidity in those with a more settled PCA-ness. Settled doesn’t mean rigid—but from a labile, process-oriented standpoint, it can seem that way. Paradoxically, then, an approach which strives to overcome polarisation and over-characterisations can end up recreating it—something I know that I have been accused of. And, indeed, dichotomising, as here, between ‘process-’ and ‘outcome-oriented’ understandings of PCA can be seen as one further instance of that mischaracterisation. But then, without trying to articulate differences—even if they are only initial approximations—how does one grow and develop and reconceptualise new thinking? From a process-oriented standpoint, that’s the prime person-centred directive.

From a process-oriented standpoint—where how we relate and engage with each other is part of what it means to be person-centred—there’s a striving (albeit, inevitably, also a failing) to try and engage with difference in respectful and valuing ways: A starting point of seeing the other as an actualising, prosocial being, doing their best; and respecting that there may be multiple truths. I guess that is what I am trying to do here. As we move away from a process-oriented understanding, however, that emphasis becomes less important. So, for instance, at times when I’ve challenged by what’s felt like very critical, judgmental language on person-centred social media sites, the response has been that empathy and acceptance is what we do with clients—it’s not relevant outside of that context. Similarly, for me, referring to other members of the community as ‘illogical’ or ‘fallacious’ just doesn’t seem the spirit of PCA, but that’s because I’m reading PCA as a process and a way of relating, rather than as a territory that needs protection. From a process-oriented standpoint, then, dialogue within the person-centred community should, itself, be person-centred, meaning:

Self-reflexivity: Recognising that one speaks from a situated perspective rather than absolute truth, and taking ownership of that position.

Contextual awareness: Acknowledging the cultural, social, and political contexts shaping one’s views, including associated power, privilege, and disadvantage.

Openness to strengths and limits: Appreciating both the value and the limitations of one’s own standpoint.

Emotional and relational awareness: Being willing to explore the emotional, interpersonal, and group dynamics connected to one’s views, alongside logical and empirical considerations.

Empathic acceptance of others: Striving to understand and value the other’s perspective as a meaningful expression of their experience and actualising tendency, while remaining able to sensitively challenge limitations.

Respect for experiential authority: Recognising the other as the expert on their own experience and avoiding assumptions about their motives, especially negative ones.

Openness to revision: Willingness to reconsider and adapt one’s views when limitations or errors become apparent.

Client-centred: Oriented to what may be best for clients (drawing on, for instance, research evidence, personal experience, and a recognition of client diversity) rather than oriented to the needs and wants (conscious or unconscious) of therapists.

Authenticity and transparency: Seeking to communicate honestly and congruently while acknowledging the subjectivity of one’s perceptions.

Collaborative engagement: Seeking both common ground and respectful exploration of differences.

Valuing diversity and minority perspectives: Respecting difference and recognising that validity is not determined by majority agreement.

Plurality of ways of knowing: Remaining open to insight from personal experience, theory, logic, and empirical evidence.

Commitment to ongoing dialogue: Understanding dialogue as an open-ended, evolving process that embraces nuance, complexity, and growth.

Just to reiterate, I know, on the basis of such principles, I have frequently failed. These are also by no means definitive. From a process-oriented standpoint, though, it makes sense to sketch out some principles by which we can maintain person-centredness with each other in our intra-community dialogues.

From an outcome-oriented PCA, there’s a right and a wrong and, I’m sure, those from such a perspective will see the blog here as illogical, unnecessary, and counterproductive—just one more attempt to undermine the truth of PCA. From a process-oriented standpoint, however, there has to be an attempt to hold both sides of the argument: to strive to empathise with disagreement and difference and try to come to a place that synthesises knowledge and wisdom from across the person-centred field. I know, for myself, I often fail at that, but for a process-oriented understanding of PCA to have any meaning, it has to be open to something other than what it is.

In some ways, I guess one could say that a process-oriented understanding is about being person-centred as a person-centred therapist, it’s a meta- perspective, while an outcome-oriented understanding is about doing person-centred therapy as a specific form of practice. And both of these are necessary, just as there is an essential dialectic between Buber’s I-Thou and I-It stances, respectively.

Both process- and outcome-oriented perspectives strive to put the client at the heart of their approach, and both emphasise the importance of tailoring the therapy to the particular client. A process-oriented approach, however, probably allows for a broader possible range of methods and styles of therapy, emphasising flexibility and openness of what it means to be PCA. However, in-the-room, many of those who frame PCA in an outcome-oriented sense would also emphasise the pluralistic nature of the approach. Where PCA, however, is defined, outcome-wise, more in terms of an empathic unfolding response process, so the range of methods is likely to become narrower.

Is there the possibility, then, of finding some kind of meeting or synergy between these two positions? Can we develop a coherent approach that also has the potential to grow and embody its own principles of openness and respect to difference?

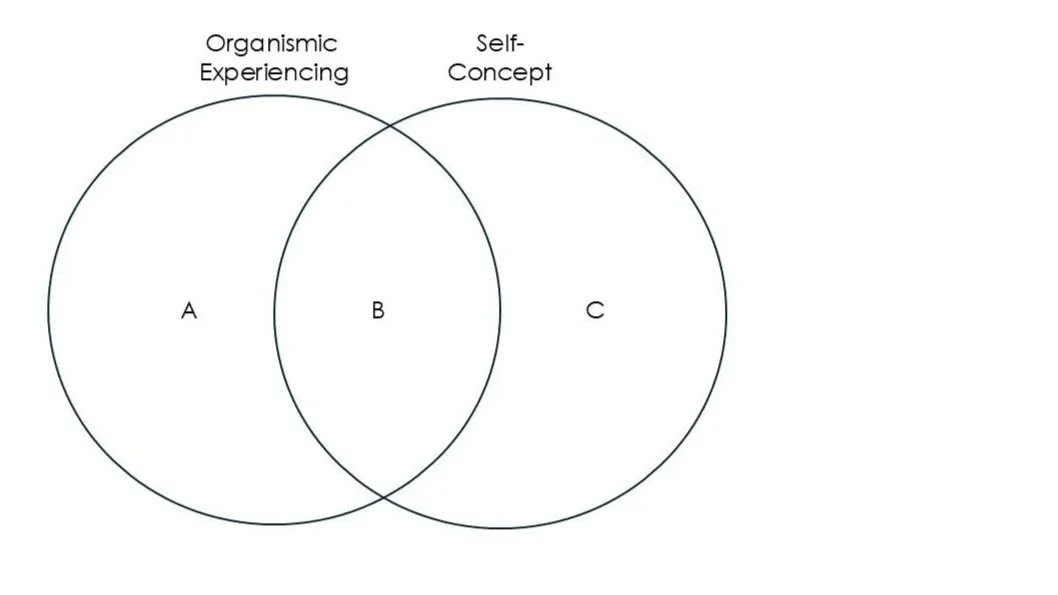

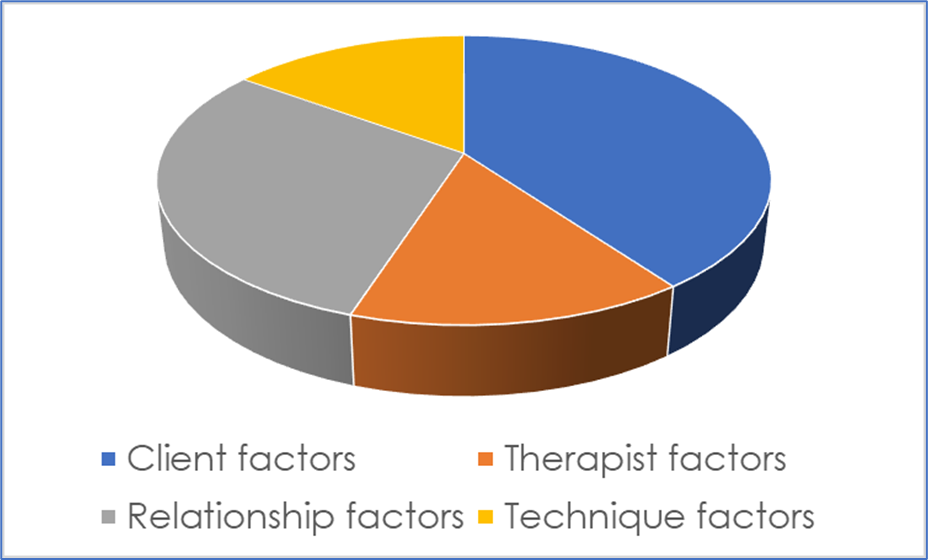

For me, personally, I think one big thing is letting go of Rogers’s six conditions are the core of PCA. These are a brilliant set of conjectures, and they give a compelling, often very accurate narrative of how change happens; but as a universal truism, they feel to me just so outdated, so far behind the latest therapy evidence: about relationship factors, therapist factors, technique factors, and personalisation. Yes, we can redefine the core conditions, to the point where empathy means bringing in to the therapeutic work any kind of intervention that we deem helpful at that time (in a non-authoritarian way), but then the principles of person-centred practice become so diffuse, so unspecified, that it is hard to tell any more what person-centred therapy is. For me, putting ‘nondirectivity’ at the heart of person-centred practice—defined, for instance, by Susan Stephen as, ‘an attitude held by the therapist from which they trust and relate to their client as a person with agency, autonomy and the capacity to grow in response to their own unique experience in the world’—would allow the person-centred approach so much more space to grow. Or, for instance, orienting it around Margaret Warner’s levels of interventiveness and the limits to that, as Murphy et al. (2025) suggest.

For me, emotion-focused therapy and motivational interviewing are also great examples of expressions of person-centred therapy which have both form and trajectory. Based on person-centred principles of empathy and prizing, they’ve grown in steady and measured ways through clinical experience, expertise, and robust research. They are, perhaps, two of the most clearly specified of person-centred practices, with clear guidelines on what is both prescribed and proscribed, but they are also constantly evolving organisms: learning, extending, striving to move steadily closer to what is of most help to clients.

Of course I’m going to say this, but I also think that a pluralistic approach to person-centred therapy is a good synergy. What does that actually mean? Nicola Blunden has described it very well in the latest Tribes book and, for me, it’s about basing a practice around the ‘core conditions’—with empathic reflections, prizing, and relational depth—but also being open to, and accommodative of, other skills and competences (that the therapist is qualified in), as identified and developed in collaboration with the client. Sometimes, then, that means the therapist leading, and bringing in new methods and techniques, with a real tailoring around the individual needs and wants of the particular client. It’s an open, adaptable, integrative practice of PCA: fluidly moving with the client in a collaborative and transparent way.

Here, one of the most common criticisms is, ‘Yes, exactly, but that’s what person-centred therapists already do’, and I am sure that is true to some extent. In that, then, we all seem to be on the same page, and whether you call it ‘pluralistic person-centred therapy’ or just ‘person-centred therapy’ it really doesn’t matter. But I also would challenge the assertion that such flexibility and personalisation is inherent to all person-centred practice. Empirically, for instance, we found that around one-third of young people wanted more input from person-centred therapy, with a similar proportion finding the silences awkward. Clearly here, it seems to me, some clients are experiencing person-centred therapy as inadequately active. Or take the finding that experienced supervisors, themselves, rated person-centred therapy as having lower levels of therapist directiveness than Gestalt, integrative, or transactional analysis approaches (see here). If the person-centred approach is, inherently, as active and as integrative as other orientations, this really needs some empirical demonstration.

Furthermore, if such active collaboration really is what the PCA is already about, then let’s explain it, and describe it, and elaborate on what we’re talking about. Let’s put it in our competences and adherence measures, where it’s currently almost entirely absent (see, for instance, here). And, research-wise, there are so many questions to answer. For instance, what is the place of psychoeducation in person-centred therapy, and what are the subtleties, the nuances, the border conditions where, perhaps, a certain introduction of psychoeducation isn’t person-centred but another way of introducing it is? If it’s person-centred, for instance, to ‘bring ideas, interpretations, suggestions or the like’ from the therapist’s frame of reference, ‘in a way that the client could easily use them in the therapy process or let them go,’ that sounds great, but how do we know that, do that, judge that? How can we develop those skills and practices, that ability to ensure clients really do feel able to let them go (bearing in mind, for instance, deference effects)? Is it mis-characterising the PCA to say that this isn’t all, already, sorted? From a process-oriented standpoint, there is always more to learn and improve on. Empirically, for instance, we found that around one-third of young people wanted more input from their person-centred practising school counsellor, with a similar proportion finding the silences awkward. And then there’s the findings of the PRaCTICED trial—that’s the kind of thing that keeps me up at night, feeling that we have to evolve. From an outcome-oriented perspective, citing such research is further attempts to undermine the coherence of the PCA. From a process-oriented perspective, they’re challenges that we need to open ourselves up to.

And also, what are then the boundaries between PCA and other approaches? For instance, if we take Susan Stephen’s definition of nondirectivity, then are we saying that other approaches don’t ‘trust and relate to their client as a person with agency, autonomy and the capacity to grow in response to their own unique experience in the world’? Is that where other approaches end and PCA begins? For me, while I like the potential in that definition, I think it needs much more nuancing, reflection, and research to really be able to bring out the unique potential of PCA. My suspicion is, with the emergence of the pluralistic approach as well as, I am sure, many other factors, the definition of PCA has been really thrown into flux in recent years. Those from an outcome-oriented standpoint defend its coherence, but what is it, specifically, they are defending (above and beyond their own, intuitive ‘knowing’ of what the PCA is)? With an outcome oriented approach there is a risk that a lot of the intrinsic process, the growth and flux and change, gets covered over.

One of the comments I’ve had from colleagues in the person-centred community, like Chris Molyneux, is, ‘I don’t have a problem with pluralism, just don’t try and pass it off as person-centred—go do your own thing.’ On the one hand, I can see what Chris is trying to say: from a classical, UK outcome-oriented PCA, the prospect of pluralism can seem very alien (although, as above, there is also the somewhat contradictory critique that pluralism is unnecessary as it’s what PCA therapists do already). But I guess, in my heart, I fear that an exclusively outcome-oriented reading of Rogers, without any of the process-oriented understanding, loses so much of what Rogers was saying (as I understand it). And I really worry for the future of the PCA if it doesn’t engage with the critiques or the research and evolving in a process-oriented way. Yes, Victorian houses are beautiful, but they can also have leaky plumbing, creaking walls, and terrible insulation: some renovation and updating isn’t the end of the world. And, perhaps to stretch the metaphor further, not everyone can afford a Victorian house: if we want PCA to be available to all, we maybe need to think about how it might be tailored, adapted, and promoted to optimise accessibility. Again, I guess my concern is that colleagues like Chris, with the best of intentions, will take the PCA into a cul-de-sac from which it will never re-emerge.

Many of us love the person-centred approach, we love Rogers’s work, and we love it and identify with it in different ways. Of course, from a process-oriented person-centred standpoint I am going to say, ‘let’s embrace that difference’, but I also want to fight (with myself) to recognise that clearly circumscribed, well-boundaried practices are important too. Stability and change, definition and porousness, openness and firmness, doing and being, ‘it’ and ‘Thou’, all have their place. The challenge is finding a way of bringing them together, and bringing them together when that very act, itself, reflects only one half of the dialectic. It’s a conundrum, but one I hope we can find ways forward on over the coming years.

Acknowledgement

Photo by Ahmad Odeh on Unsplash. Thanks to Xabi at https://xabierlopez.co.uk/about-me/ for the graphic image.