My mum was born on the 17th December 1932 in east Berlin as ‘Kitty Furstenberg’. She was the first child of poor Jewish parents: their unhappiness compounded by constant quarrelling. Walter, her father, had come out of the French foreign legion, and was struggling as a door-to-door salesman—Jews were barred from most occupations. Her mother, Betty, met her father in a Jewish youth organisation—Betty like all the girls, had been in love with the leader of the youth group: Walter’s handsome older brother, Solly.

Kitty was named after her paternal grandmother, Kreindla (or Katie) Wixon. However, there were so many ‘Katies’ already in the family—including my mother’s favourite cousin ‘Little Katie’, and ‘Big Katie’—that they chose the name ‘Kitty’ instead. Apparently, Kitty’s mother took the name from a Tolstoy novel she had been reading.

Kitty described her childhood in Berlin as a time of terror, abandonment, and isolation. One of her most frightening experiences—that she told me several times as a child and again when Ruby and Maya (my eldest daughters) and I interviewed her in 2010—was of a day when she and her mother had gone to the Gestapo offices. This was something that Jews were forced to do: to show that they were still living in Berlin, and that they were making every attempt—as all my mum’s family were—to leave. One visit, in early 1939, my mother overheard an elderly Jewish woman being told by the Gestapo officer that she had to leave Germany in two or three weeks. The elderly woman said that she had nowhere to go—she couldn’t get out. The officer replied that that wasn’t his problem, and that if she didn’t leave, she would be taken away. I think that was the point that my mother, just a young child, realised that her and her family’s life was in mortal danger.

My mother lived through Kristallnacht, the 9th November 1938, when so many Jewish properties were destroyed and Jews were taken away. She remembered that her father hid in a cousin’s flat: the cousin had already been taken, so my mother’s parents thought that the Nazis would not search there. My mother remembers being told that, if the Nazis did come and asked where her father is, she should say that she didn’t know.

Unlike many of my mother’s extended family who died in the holocaust—including ‘Little Katie’—Kitty and her mother were able to leave Berlin and travel to England to join her father. This was in August 1939, just three weeks before the war broke out. Kitty and her parents were guaranteed to come to England by an uncle, Bernard, who was already living here. There is a haunting photo of my mum’s extended family—all dressed in their finest clothes—saying ‘goodbye’ to Kitty and her mother on the platform in Berlin, my mum sitting on her suitcase. Kitty would never see these family members again. My mum also told the story of how, when she and her mother got to immigration at Dover, it was realised that my mum had not been put on the visa. She should have been refused entry and sent back to Germany. But the immigration officer took pity on her and waived them through. My mum always said that, if it hadn’t been for that kindly English officer, ‘it would have been the end’. She was right.

Kitty and Family at the station platform, Berlin 1939

More abandonment was to come. Three weeks after Kitty arrived in England, she and her classmates were evacuated to Norfolk. Kitty’s mum—who was afraid to tell her that she was going away for some time—had told Kitty that she was just going on a day trip. ‘It was a terrible, terrible shock to me,’ said my mum, ‘I was there for 18 months and cried every day.’ The family she went to were stern, though kindly, and to make matters worse my mother hardly spoke English. In fact, she said, she initially refused to learn English—she told others that they should learn German instead!

Eventually Kitty returned to live with her mother, moving across different rental apartments and primary schools in London. Kitty’s father, who had worked as a welder on the undersea pipeline that supplied the Normandy landings with oil, came home after the war. But that was not easy for Kitty, who was by now 12 years old. She had had relative freedom with her mother, who she described as ‘easy going’, and when her father returned to ‘lay down the law’—bringing home all of his military discipline—Kitty, as well as her mother, were not happy. ‘I was quite a rebellious teenager,’ said my mum, ‘I didn’t want to do anything my parents wanted me to do, I had my own mind of what I wanted to do.’ As a consequence, homelife was often fraught with tension and argument.

Kitty, centre, with friends

Kitty was delighted, however, when her younger sister, Sandra (who Kitty had named ‘Alexsandra’) was born in March 1945. Kitty adored her sister: a close friend, confidant, and companion throughout her life.

The two girls lived with their parents in a prefab on Gayhurst Road, Hackney. Around 1956, they moved to a house in Wood Green. Kitty’s mother worked as a seamstress, and her father set up a small metal welding business.

Kitty went to John Howard Secondary School in Hackney, leaving at the age of 15. She then attended commercial college to learn shorthand typing, which she described as ‘absolutely hating’, and subsequently took up secretarial work. When I was a child, she would tell us about some of the jobs she had, like working for Psychic News. She also worked in the El Al offices, and was there at the time of Eichman’s capture and transportation to Israel.

I didn’t know this, but when we interviewed my mum in 2010 she said that her favourite hobby as a girl had been stamp collecting—like Davina. And she ‘just loved reading books’—as anyone who spent time with her would know. Mum described going to the Hackney Library as a child and finding books that looked interesting: she loved novels, and authors such as Aldous Huxley and John Steinbeck. When my young kids looked at her bewildered, she explained, ‘because there was no television’. Kitty, throughout her life, was a woman of culture: not just literature but also art, photography, and theatre. As a young woman she also loved dancing and would go, either with friends or on her own, to ballroom dancing in Knightsbridge.

When my mum said to Maya and Ruby, in our 2010 interview, ‘What would you like to ask me?’ the first thing my girls said was, ‘Can you tell us about your past boyfriends?’ My mum said that her first great love was an Ethiopian man, then her boyfriend Silvio. Then she met Charles when she was 25 and Charles was 47. ‘Once I met Charles and once I fell in love with him, that was it,’ Kitty said.

Charles and Kitty had met at philosophy evening classes in the late 1950s. After classes, they would go for coffees with friends, and my dad—who was establishing himself as a leading UK film distributor—would tell everyone the latest news from the film industry.

Tragically, as my mum was to find out, Charles’s first wife, Cecilia, had recently died. She was just 44 years old, and together Charles and Cecilia had had two young twins—Adi and Sue—and an elder daughter, Florence.

My mum said that her first date with Charles was at the Curzon Cinema, seeing a Brigitte Bardot film. Kitty was quite shocked that my dad had taken her to something so ‘low brow’, but she discovered later that Charles had had complimentary tickets to the showing.

Kitty and Charles in later life

Kitty and Charles dated for several years. ‘He was very handsome, very presentable, and had all these women who wanted to marry him,’ said my mum. A few times, reported Kitty, she was so upset with Charles for not making things more permanent that she would ‘pack him in’—even moving up to Edinburgh to study at the University—but then they would always get back together because they both loved each other so much.

In 1964, my parents married. Davina was born in January 1965. Sadly, at the same time as Kitty was pregnant, her father Walter had died.

I was born in April 1966. As a young child, I remember my mother as a warm, loving, youthful presence. I always wanted to spend time with her: she was fun. We would play chess together, cards, watch TV. I remember sitting on the top of the bus with my mum as she took me to my speech therapy appointments. My happiest times—my ‘safe space’—was lying between my mum and dad in their bed in the mornings, cuddling them; jumping up and down, then cuddling more. Charles, as well as Kitty, had come from a family background with lots of highly expressed emotions, and so they both wanted to forge a family life that was calm and conflict-free. I never saw them argue. Kitty described her time with Charles as the happiest in her life. The home that they created together in Highgate from 1973—and which my mother stayed in until the end of her life—was a happy and welcoming environment for us and for so many children, grandchildren, family, and friends: a place of stability, vitality, and love.

My mum was a fiercely intelligent woman: she was a demon at Scrabble into her 80s, and she often told us how her name was on a plaque at the University of Edinburgh for getting the highest economics mark for her first year of study. After marrying my father, she went on to work at their company, Contemporary Films, running the International Department. She was a successful businesswoman in her own right, dealing with many of the leading figures in the cinema world, including Agnes Varda, Werner Herzog, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Jean Renoir.

Kitty was deeply political: committed to making the world a fairer and more compassionate place. She joined the Communist Party, alongside Charles, and actively engaged in party meetings and demonstrations.

Friendships, too, were an essential part of her life. She loved, and was loved by, many. Her oldest friend was Ruth Gilbert, who sadly died several years ago; and there was Anita, Pam, Kate, Lilian, Dorothy, Maggie Bowden, Michael Israel, and many, many others. My mum was a wonderful listener and always interested in others—she never put her ego first. She always had time and space for others: a calm, compassionate presence.

Charles died in 2001, after being cared for by Kitty for several years. It was a terrible loss for my mum, and she never really recovered. She missed him enormously and would sometimes see him walking around their Highgate home. Yet, as well as her children and friends, she had a growing brood of grandchildren that she spent time with and loved: Daniel, Jesse, Hannah, Emma, Frania, Rivka, Shane, Maya, Ruby, Shula, and Zac—and then nine great-grandchildren. It was amazing to see, in the hospital before she died, how many people had come to say their goodbyes: from her two-year old great-grandson Ollie to decade-long friends like Lilian.

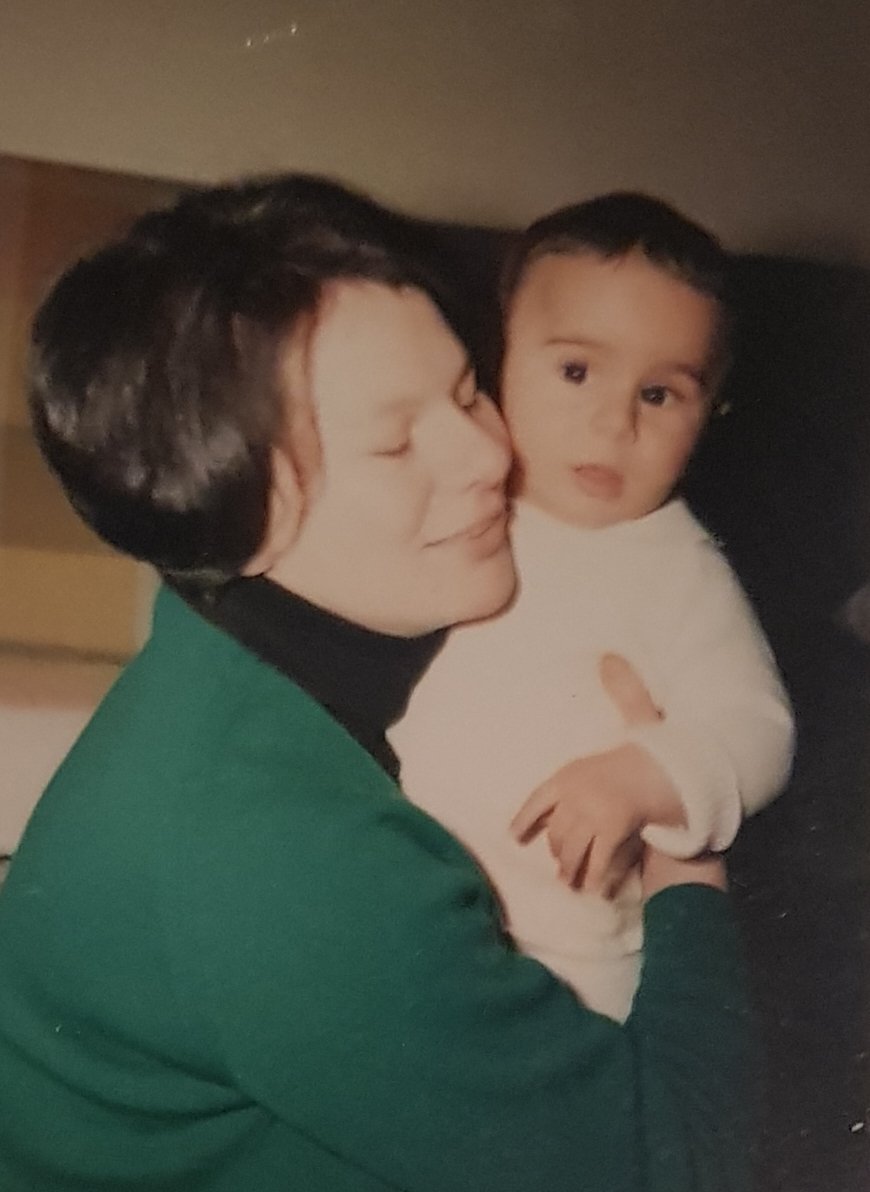

Shula, Kitty, Zac, and Maya

The last thing my mum said to me, about a week before she died, was that she loved me. And I really felt that from my mum. We had our moments, but I always felt a deep, enduring, and unshakeable love from her. And I know that she felt that towards so many others: her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren; her sister and wider family; and all her friends—so many of whom are here today. Trauma, as we know, can do terrible damage to a person’s capacity to attach and relate. Yet my mum, despite all the terror, isolation, and abandonment that she experienced as a child, had a tremendous ability to love and be loved. She connected, cared, drew others in and held them with so much warmth and affection. That capacity to love so deeply and so consistently—despite what she had endured—can only be testament to her remarkable resilience, intelligence, and strength of character. That is truly something, and someone, to celebrate.

Links

The Guardian ‘Other Lives’ obituary, Kitty Cooper, written by Davina

Jewish Chronicle obituary, Kitty Cooper

Blog post: my reflection and memories of visiting my parents’ in their Soho office

Correspondence on my grandmother, Betty Wixon, created by my mother, regarding my grandmother’s estate and German pension