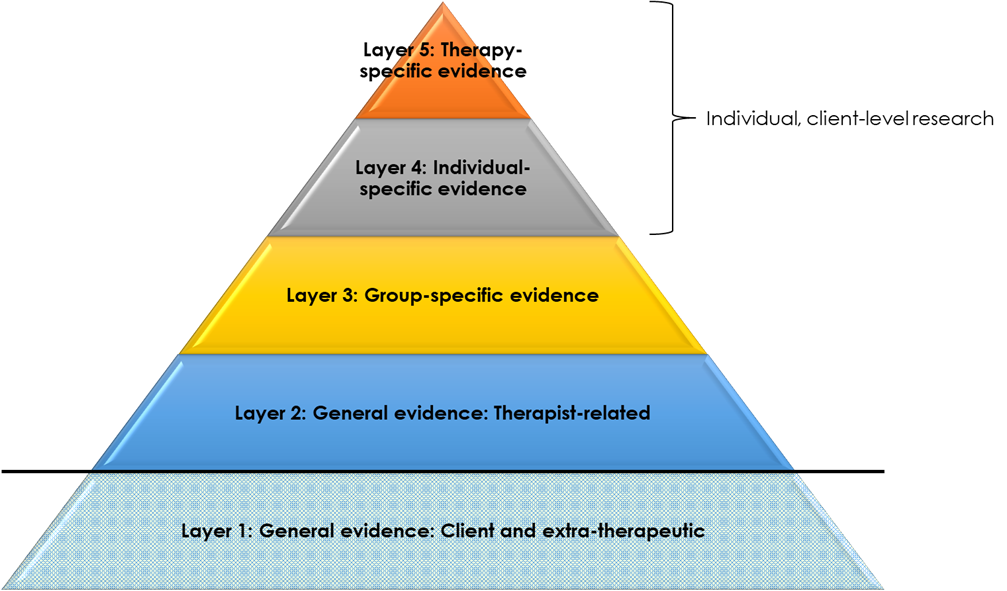

How can we use research data to inform and improve therapeutic practice? When I wrote my book Essential research findings in counselling and psychotherapy (Sage, 2008), I did what most writers in the field had done: I tried to organise and make sense the evidence by different ‘factors’. I used the usual suspects: client factors (e.g., the client’s motivation); therapist factors (e.g., the therapist’s gender); relationship factors (e.g., the amount of goal agreement); technique and practice factors (e.g., using two-chair work); and orientation factors (e.g., working in a person-centred way). That gave a fairly simple and clear taxonomy and meant that it was possible to describe the relative contribution of different factors to therapeutic outcomes. For instance, one might estimate, based on the most recent evidence, that approximately 40% of variance in outcomes is due to client factors; 30% due to the relationship; 15% to therapist factors; and 15% due to the particular techniques, practices, or orientation used. This can then be neatly depicted in a pie chart, like Figure 1.

Figure 1. Illustrating the Contribution of Different Factors to Therapeutic Change

Despite its clarity, organising research evidence in this way has its limitations. One very obvious one is that it implies that each of these factors is discrete when, of course, they are likely to inter-relate to others in complex, mutually reinforcing ways. Another problem, more directly related to the framework developed in this article, is that they tend to infer that each client is influenced by each of these factors in the same way and to the same extent: that relationship factors such as empathy, for instance, lead to 30% of outcomes for Client A, and also for Clients B, C, and D. The reality, however, is that Client A may do very well with empathy while Client B may not; and while relationship factors may be essential to Client C’s recovery, Client D may do very well without them. Indeed, much of the cutting edge research in the psychotherapy field—by leading figures such as Zachary Cohen and Jaime Delgadillo—is on the particular factors that lead particular clients to do particularly well in particular therapies; and the algorithms that can then be developed, based on such evidence, to optimise benefit. Organising the evidence by factors may also limit its utility for therapists. As practitioners, we do not tend to think about our work, systematically, in terms of these different factors (e.g., ‘What can I do to improve myself as a therapist?’ ‘What can I do to improve my relationship?’); and it is also important to note that different factors may have very different implications for practice. Knowing, for instance, that clients with secure attachments do better in therapy than those with insecure attachments (a client factor) does not really tell us anything about how to work; while knowing that clients tend do better when their therapists are warm and genuine can have important implications for practice. So although these factors, in Wittgenstein-ian terms, have a ‘family resemblance’, they are actually quite distinctive things.

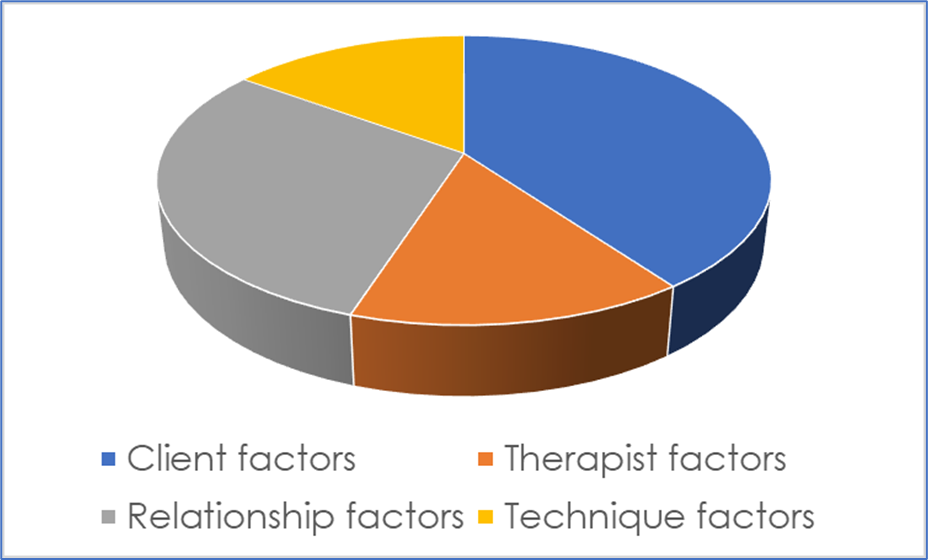

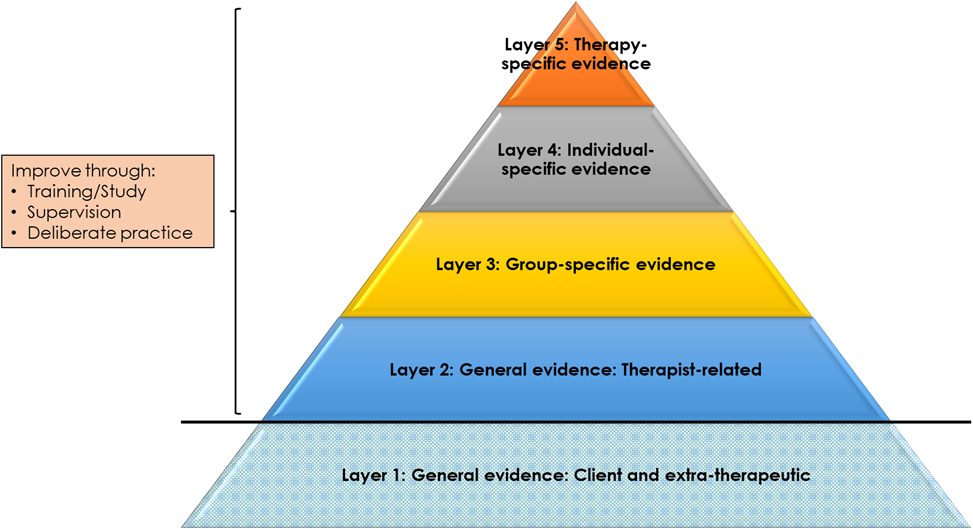

The aim of this article, then, is to describe a way of organising and conceptualising therapy research evidence that addresses some of these problems: allowing for a more nuanced, comprehensive, and personalised conceptualisation of data; and potentially more useable by therapists. The essence of this framework is a pyramid (or funnel, see Figure 2), with different layers of evidence at increasing degrees of specificity and proximity to the client. Each layer builds on the previous ones: from research evidence that is relevant to all clients to research evidence that is specific to a particular client in a particular session. As this pyramidal form suggests, as we move upwards, evidence may become more sparse. However, because of its greater specificity, and because it is most proximal to clients’ actual experiences—such evidence may be of greatest value. For instance, research suggests that clients generally do better when therapists are empathic (Layer 2), but if evidence exists that the opposite is true for highly paranoid clients (Layer 3), then the latter finding would tend to take precedence to guide practice with a highly paranoid client. However, if it was then established that, for a particular highly paranoid client, they had a strong preference for an empathic therapist (Layer 4), then this higher-layer evidence would take precedence over the group-specific (Layer 3) finding.

Figure 2. A Pyramidal Framework for Organising Therapy Research Evidence

The foundation of the pyramid, Layer 1, is general evidence on client and extra-therapeutic factors that tend to determine good outcomes. For instance, clients who are psychologically-minded tend to do better in therapy, as do clients with more social support. These factors are separated off from other factors (depicted in Figure 2 by a dividing line), because they are less relevant to what therapists do. Rather, they are the grounding—to a great extent outside of the therapist’s control—as to how therapy is likely to proceed. In this respect, these general factors have an important role in predicting outcomes—and, indeed, may explain by far the largest proportion of variance—but do not have much role, per se, in informing or shaping how therapists work.

Note, the term ‘tend to’ indicates that, while these findings are drawn from generally representative samples (or samples assumed to be generally representative), this is not to suggest that these factors will be true for each and every client. Rather, this is evidence, across all clients, of averaged tendencies, around which there will always be considerable group-, individual-, and session-layer variance.

Building on these general client and extra-therapeutic factors are general factors that are related to the therapist and their therapy (Layer 2). This includes therapist factors (for instance, therapist gender), relationship factors (for instance, the alliance), and technique factors (for instance, use of cognitive restructuring). These are findings that reach across all clients and, although still averaged trends, can be very useful for therapists to know. In the absence of any other information, they provide a useful starting point for work: for instance, be empathic, listen, or self-disclose to a moderate extent.

At a greater layer of specificity (Layer 3) is evidence of particular factors that tend to be associated with helpfulness for particular groups of clients. By far the greatest amount of evidence here focuses on clients grouped by particular mental health diagnoses—for instance moderate depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder—as reviewed and operationalised, for instance, in National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines. Considerable research is also now available on clients with particular cultural identities (e.g., people of colour, lesbian clients), and what tends to be most effective for them. There is also a wide range of research on other ‘aptitude–treatment interactions’ which identifies the factors that tend to be most effective with particular groups of clients. For instance, clients who are more reactive tend to do better in less directive therapies, while the reverse is true for clients who are more compliant. Of course, clients may be members of multiple groups—‘intersectionality’—such that practices indicated may be complex or, potentially, contradictory. Tailoring therapies to particular client characteristics is what Barkham terms ‘precision therapy’, linked to the wider development of ‘precision medicine’: ‘predicting which treatment and prevention strategies will work best for a particular patient’ (NHS England).

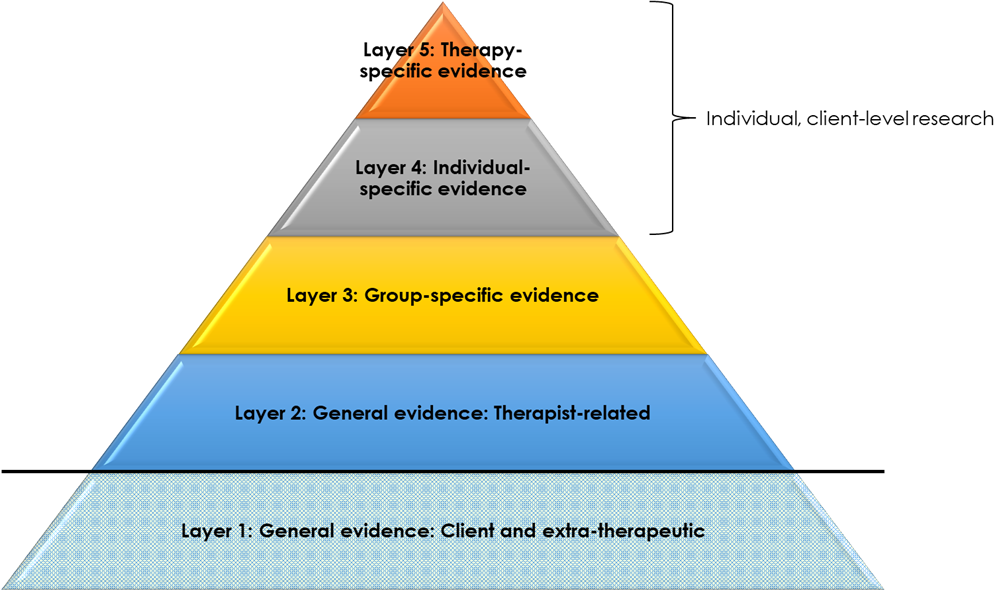

Moving up in specificity, to Layers 4 and 5, entails a shift towards individual-level research and data gathering (Figure 3). This is, perhaps, the most important and novel part of the framework being suggested here, because a continuum is being proposed from (a) general- and group-level research to (b) contemporary, individual-level monitoring: one segues into the other. In other words, the framework suggests that what researchers do ‘in the field’ is not so different from what therapists do when they are working with individual clients using routine outcome monitoring (ROM): it is all part of one broad spectrum of using data to help inform practice. This may be helpful for practice because it de-mystifies ‘research’ and puts it on a equal footing with things that a practitioner would typically do. Now, research about populations or groups is not something that researchers do far away on some other planet, but is an extension (broader, but less specific and proximal) of what therapists are, actually, doing all the time. That does not mean it can be waived away, but it does mean that it can be considered a friend rather than enemy (‘the facts are friendly’, as Carl Rogers said).

Describing individual-level data gathering as ‘research’ is a somewhat unusual extension of the term. Almost by definition, ‘research’ is seen as involving generalising from specific individuals to the wider group or population. However, if research is defined as ‘a detailed study of a subject, especially in order to discover (new) information or reach a (new) understanding’ (Cambridge Dictionary), then generalisations can also be at the individual client layer: from, for instance, one session to another, or from assessment to across the course of therapy as a whole. Individual-layer research like this is not something you would see published in a journal, nor could it be summarised in a book like Essential research findings. Even with individual-focused research methods like autoethnography or heuristic research, the aim is to reach new understandings that are of relevance across clients or contexts. But with the individual client-layer research described here, the aim is solely to use data to reach new understandings about this individual client. It is a form of systematic enquiry which the therapist, themselves, does, to help optimise their therapeutic work with the client by drawing on data.

Figure 3. Individual Level Research

Layer 4, like Layer 3, entails the use of data, prior to the commencement of therapy, to estimate what is most likely to be helpful for a client. While Layer 3, however, makes such assumptions on the basis of group characteristics, Layer 4 focuses exclusively on that client’s individual uniqueness. This is the complex, rich mixture of characteristics and experiences that make the person who they are: irreducible to any particular set, or combination, of group characteristics. In terms of system theory, this is their ‘emergent properties’; in terms of the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, their ‘otherness’. Understanding how data at this layer may be captured and integrated into therapy is, perhaps, the least well-developed element of this framework. However, one notable and well-researched element here is the client’s preferences: recorded, for instance, on our Cooper–Norcross Inventory of Preferences (C-NIP) at assessment. The focus of such individual layer research, then, is on what this specific client needs and wants from therapy; and the incorporation of such findings into the therapeutic process.

Finally, at the highest layer of specificity (Layer 5), is the use of data to guide the ongoing process of therapy, as in the well-researched and -developed practice of routine outcome monitoring (ROM). In ROM, the therapists uses data from ‘outcome forms’ (like the CORE-10 or PHQ-9), and potentially also ‘process forms’ (like the Session Rating Scale), to track how the client is doing, and to try and adjust the therapy accordingly. For instance, if the client’s layers of symptoms are worsening, the therapist may draw on pre-specified ‘clinical support tools’, such as a protocol for reviewing the therapeutic alliance with the client. In this way, ROM can be considered research at the highest layer of specificity: generalising from data captured at particular points in therapy (for instance, at the start of each session), to the therapeutic work as a whole. Barkham terms this in-therapy, iterative uses of data as ‘personalisation’—distinct from the ‘precision’ tailoring of Layers 3 and 4.

Note, even at these highest layers of specificity, data still only ever gives indications of what might be of benefit to a client at a particular time, not what is. Client preferences, for instance, tell us what a particular client thinks will be helpful, but there are no guarantees that such practices are of benefit; ROM predicts when clients may most be ‘off track’, but there are still numerous sources of ‘error variance’ meaning that, in fact, some of these clients may be doing very well (what has been termed ‘paradoxical outcomes’). As we move up the layers, then, we may move from distal to proximal forms of evidence, less to more trustworthy, but even at the highest layer, we are only ever dealing with approximations. Hence, while higher layer data, where present, may deserve prioritisation, best practice may ultimately come through informing clinical work with data from across multiple layers.

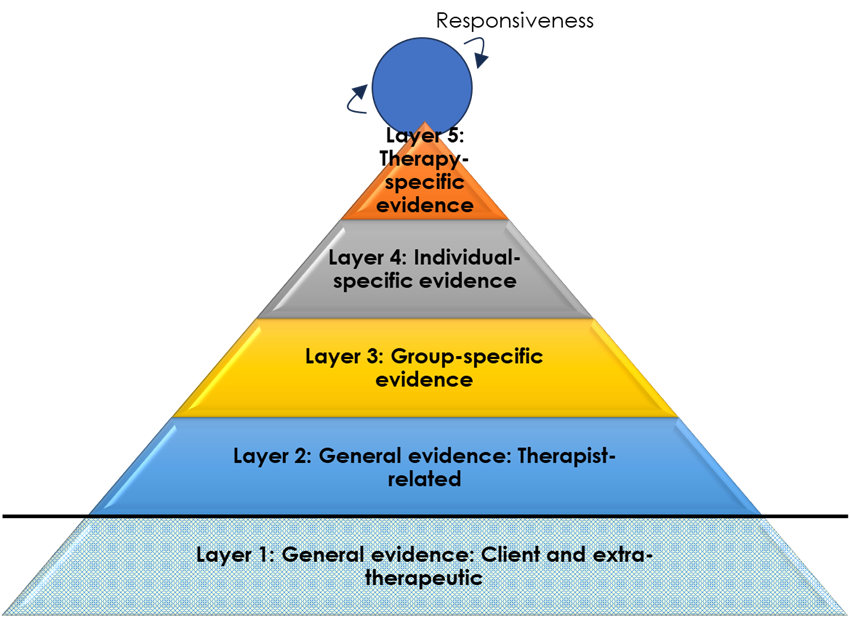

In fact, Layer 5 is probably not the highest and most specific layer of data usage to optimise benefits in therapy. At every moment of the therapeutic work, therapists will be striving to attune therapeutic practices to what they perceive—consciously or unconsciously—as beneficial or hindering to clients. A client seems to become animated, for instance, by being asked about their brother, and the therapist enquires further; a client glances away when the therapist asks about the psychotherapy relationship and the therapist seeks another way of addressing the here-and-now relationship. Stiles refers to this as therapist ‘responsiveness’, and this is represented as a spinning circle right at the top of the pyramid (Figure 4). Bill Stiles, in a personal communication, has written:

Representing responsiveness research as a (spinning?) circle (wheel? ball?) at the top seems to me to convey both the recursive feedback idea (circle, spinning) and the potentially high specificity (possibly millisecond-scale, e.g., responsive adjustments in mid-sentence due to facial expressions).

These five layers of evidence, then, segue into the moment-by-moment, ‘evidence based’ adjustments that therapists are constantly making throughout their work. And, as the highest layer, such responsiveness may be most proximal and attuned to what clients will find most helpful. Nevertheless, in the absence of such proximal information, each of the preceding layers will give valuable information about where best to start with clients. Moreover, as suggested in the previous paragraph, given the vagaries and potential errors inherent in each layer of data (including responsiveness: for instance, the therapist may misread the client’s reaction, or the client may be hiding it through deference), it is probably a combination of evidence from across the layers that is likely to be most beneficial in successfully guiding therapy.

Figure 4. Layers of Evidence Segueing into In-Session Responsiveness

Although each of these layers of evidence have the potential to inform therapeutic practice, different individuals, training programmes, or services may place emphasis on very different layers. For instance, in the IAPT model (Improving Access to Psychological Therapies, now NHS talking therapies), based on NICE guidelines, practice is nearly-exclusively drawn from evidence at Layer 3 (in particular, diagnoses-specific evidence), with little consideration for other layers (see Figure 5). Even responsiveness to the needs and wants to the individual client, during IAPT practice, tends to be subsumed to manualised, ‘evidence-based’ guidance.

NHS/IAPT Emphasis on Diagnosis-Specific Evidence

On the other hand, in approaches like Scott Miller’s feedback-informed therapy, there is a particular reliance on the most proximal evidence: the client’s immediate feedback through ROM (Layer 5), as well as a responsiveness to the particular client in the particular moment (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Feedback-Informed Emphasis on Proximal Data

In contrast to Layer 1, Layers 2 to 5 provide opportunities for therapists to enhance their practice (Figure 7). This is in two respects. First, at a basic level, skills and competences can be developed in practices that have been shown to lead to beneficial outcomes. This is particularly Layer 2 general relationship factors (e.g., enhancing levels of empathy) and technique factors (e.g., developing skills in two-chair work). In addition, at a more meta-level, knowledge and competences can be developed in tailoring practices to group- (Layer 3), individual- (Layer 4), and therapy- (Layer 5) specific evidence. For instance, at Layer 5, trainees can be taught how to use ROM data to monitor and enhance therapeutic outcomes, particularly with ‘not on track’ clients. Such training may be based on informal guidance and feedback (e.g., through supervision) or, itself, may be evidence based: using data to feed back to trainees how they are doing on particular competences. A supervisor, for instance, might rate segments of their supervisee’s audio recordings, across multiple time points, on a practice adherence measure like the Person-Centred and Experiential Psychotherapy Rating Scale (PCEPS). This moves us into the realm of ‘deliberate practice’ and, indeed, a separate pyramid could be developed for the use of research in training: from the most general evidence about factors that improve practice to therapist-specific data on what an individual practitioner might do to improve their outcomes.

Figure 7. Opportunities to Develop Therapist Competences and Meta-Competences

In fact, Layer 1 probably does also offer opportunities for enhancing the beneficial effects of therapeutic work—perhaps to a great extent—though this is rarely the focus of study or training. Here, emphasis is on how clients might be empowered or enabled to develop skills in using therapy most effectively. A good example would be the ‘resource activation’ work of Christoph Flückiger and colleagues, which invites clients to draw on their own strengths and resources to ‘drive’ the therapeutic process. In addition, this is the layer at which therapists might be developing competences in social and political advocacy practices. Developing the ability, for instance, to challenge unjust organisational policies might help to address the psychological distress brought about by racial discrimination.

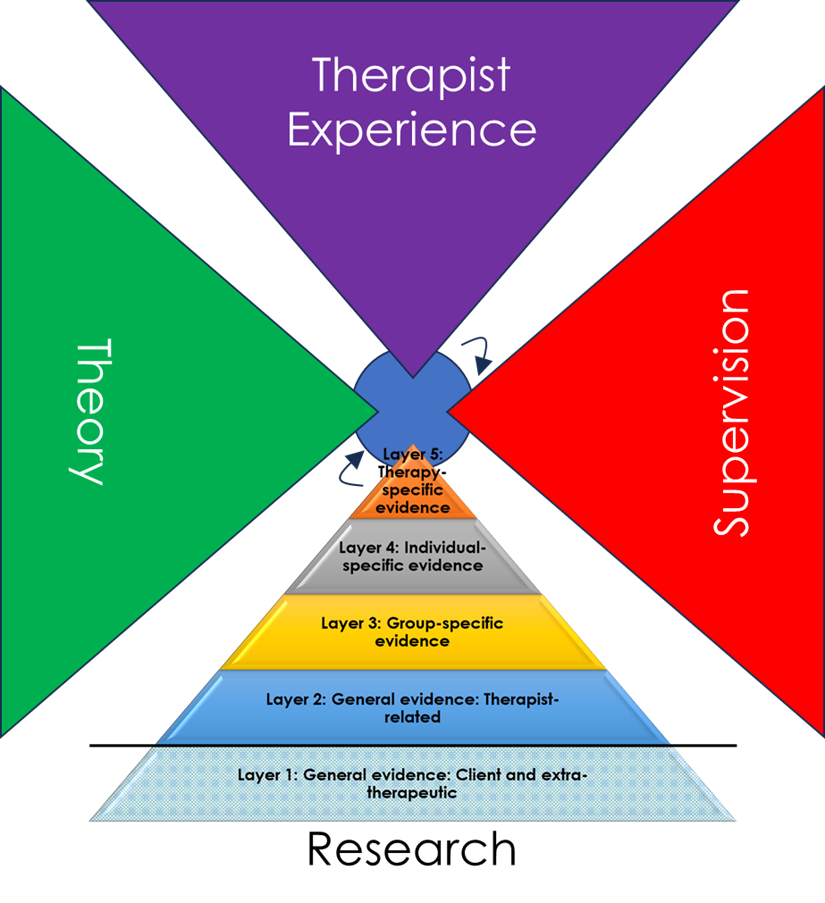

Of course, research evidence is not the only sources of guidance on how to practice. Therapists may also draw, for instance, from theory, their own experiences, and from their supervision work. These sources are likely to be interlinked in complex ways, but for simplicity sake we can present them as per Figure 8.

Figure 8. Multiple Sources of Guidance on Practice

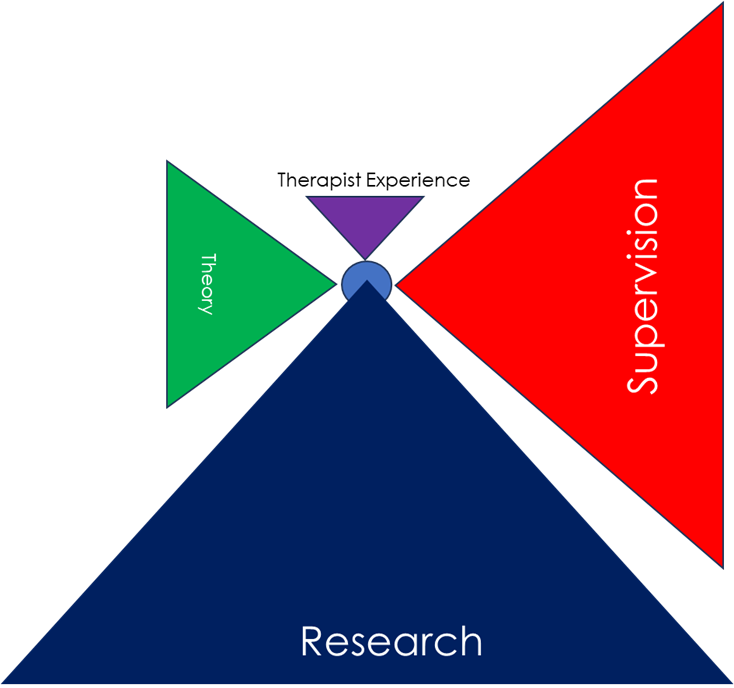

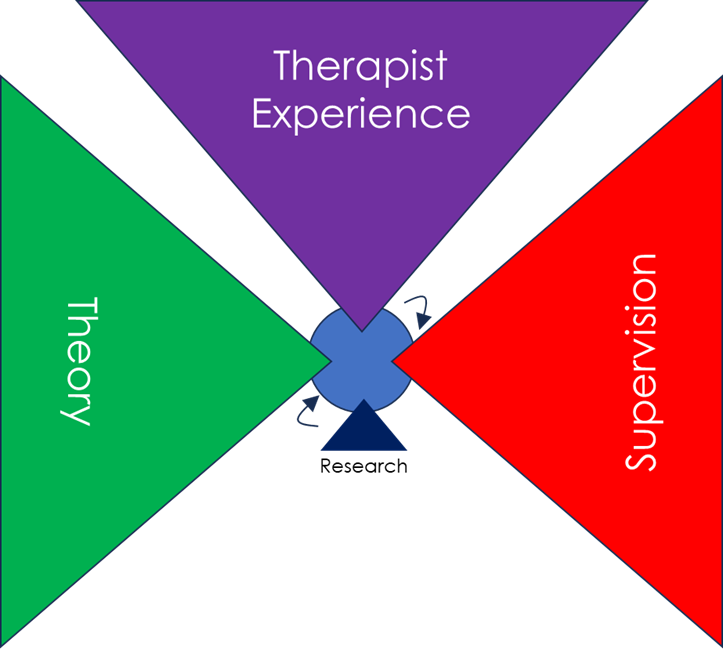

And, as with the layers of evidence, different individuals, training programmes, or services may place emphasis on very different sources to guide practice. In NHS Talking Therapies, for instance, practice is primarily based on research evidence (Layer 3, diagnosis-specific) (see Figure 9). By contrast, in much of the counselling field, practice is primarily guided by theory, supervision, and the therapist’s own personal experiences—as well as responsiveness in the specific moment—with research evidence playing only a very minor role (Figure 10).

Figure 9. Sources of Practice in NHS Talking Therapies

Figure 10. Typical Sources of Practice in the Counselling Field

Again, one might argue that, in best practice, there is an openness to drawing fully from all potential sources.

This pyramidal framework for drawing on research evidence is very different from the ‘hierarchy of evidence’ as used, for instance, in NICE clinical guidelines. While the latter ranks research according to its ‘objectivity’—placing randomised clinical trials and their meta-analyses at the top and expert opinion at the bottom—the present framework makes no assumptions about the relative worth of different methodologies. Qualitative research, for instance, may be a very powerful means of understanding what particular methods or practices are particularly helpful for particular groups of clients (Layer 3). Indeed, in this framework, the data that may be of most value to particular episodes of therapy—by being most proximal—is individualised ROM data: very different from the kind of generalised RCT data prioritised in the standard hierarchy of evidence.

Conclusions

When trying to make sense of the vast body of psychotherapy research evidence, there are many different ways of organising the research:

Different factors (therapist, client, etc)

Degree of ‘independence’/rigour of the research (the IAPT/NICE approach)

Effective treatments for different problems (again, the the IAPT/NICE approach)

Evidence for different therapeutic approaches overall

The proximity of the research evidence to the actual client and session (what is being proposed here)

Of course, there is no one right way, and these different organising principles can be combined in a wide variety of ways. For instance, the evidence at each layer of the present framework could then be organised by degree of independence of the research, or by different factors. However, each of these frameworks do prioritise and emphasise, even if implicitly, different elements of the research evidence. In the present one, there is as implicit privileging of data that is most proximal to the client—the ‘top’ of the pyramid. This can be seen as emerging from my own humanistic, existential, and phenomenological ‘ontology’ (theory of being) and ethics, which tends to reject the positivist assumption that the universe acts—and can be understood as acting—according to general, underlying mechanisms and laws. Rather, there is an emphasis here on ‘otherness’ and the irreducibility of human being. That is, that human beings’ lived-experiences can be unique, and that focusing on the unique and distinctive aspects of that experiencing is an important element—both ontologically and ethically—of understanding the whole.

Having said that, as Nicola Blunden points out in her comments below, the approach presented here is therapist-centred, in that it is a framework by which therapists can use the evidence. That is consistent with the target audience of my ‘facts are friendly’ book, but it raises the question of what a client-centred, or relationship-centred framework for making sense of the research findings would look like. Perhaps that would start with a greater focus on, and nuancing of, ‘Layer 1’ evidence: What can the client do with this to maximise their therapeutic outcomes? Nicola also raises the interesting point of whether a pyramid is still too hierarchical: would a target or spiral be a better representation of the potential use of data in therapy?

The pyramidal framework presented here is a way of organising research data to inform therapeutic practice. The pyramid builds, in layers, from the most general to the most specific evidence of what works—and is working—for an individual client. This framework does not negate a more factors-based taxonomy—indeed, it can incorporate it—but emphasises, instead, the relative proximity of different data sources to the actuality of each episode of clinical practice. Perhaps what is most useful about this framework is it provides a means of segueing from general and group-level research to individual-level research—and then, even, on to responsivity in moment-by-moment practice. This may allow a greater integration of research data into practice: research, here, is not something separate from what therapists generally do, but something spread on a continuum from the most general to the most specific. This framework is also a means of representing the way different sources of evidence may be weighted in different approaches, as well as the weighting of research evidence against other sources of clinical guidance. And while this framework does not indicate which sources (research or otherwise) should be prioritised, by mapping out possibilities in this way, it hints at the potential value of all. While this framework is a work in progress, it may be a way of organising and making sense of the research evidence that encourage a broader, more encompassing, and more pluralistic conceptualisation of all its uses.