Why bother?

Let’s say this, up front: it’s hard work getting your research published. It’s rarely just a case of cutting and pasting a few bits of your thesis, or reformatting an SPSS table or two, and then sending it off to the BMJ for their feature article. So before you do anything, you really need to think, ‘Have I got the energy to do it?’ ‘Do I really want to see this in print?’ And being clear about your reasons may give you the motivation to keep going when every part of you would rather give up. So here’s five reasons why you might want to publish your research.

If you want to get into academia, it’s pretty much essential. It’s often, now, the first thing that an appointment panel will look at: how many publications you have, and in what journals.

Even if your focus is primarily on practice, a publication can be great in terms of supporting your career development. It can look very impressive on your CV—particularly if it’s in an area you’re wanting to develop specialist expertise in. Indeed, having that publication out there establishes you as a specialist in that field, and that can be great in terms of being invited to do trainings, or teaching on courses, or consultancy.

It’s a way of making a contribution to your field—and that’s the very definition of doctoral level work. You’ve done your research, you’ve found out something important, so let people know about it. If you’ve written a thesis, it may just about be accessible to people somewhere in your university library, but they’re going to have to look pretty hard. If it’s in a journal, online, you’re speaking to the world.

…And that means you’re part of the professional dialogue. It’s not just you, sitting in your room, talking to your cat: you’re exchanging ideas and evidence with the best in the field—learning, as well as being learnt from.

You owe it to your participants. For me, that’s the most important reason of all. Your participants gave you their time, they shared with you their experiences—sometimes very deeply. So what are you going to do with that? Are you just going to use it to get your award—for your own private knowledge and development; or are you going to use it to help improve the lives of the people that your participants represent? In this sense, publishing your work can be seen as an ethical responsibility.

Is IT good enough?

Yes. Almost certainly. If it’s been passed, at Master’s level and especially at doctoral, it means, by definition, that it’s at a good enough standard for publication somewhere. It’s totally understandable to feel insecure or uncertain about your work—we all can have those feelings—but the ‘objective’ reality is that it’s almost certainly got something of originality, significance, and rigour to contribute to the public domain.

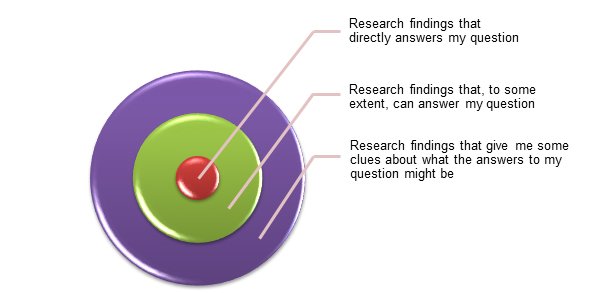

Focus

If you’ve written a thesis—and particularly a doctoral one—you may have been covering several different research questions. So being clear about what you want to focus on in your publication, or publications, may be an important next step. Get clear question(s), and be clear about the particular methods and parts of your thesis that answer them. That means that some of your thesis has to go. Yup, that’s right: some of that hard fought, painful, agonised-over-every-word-at-four-in-the-morning will have to be the mercy of your Delete key. That can be one of the hardest parts of converting your thesis to a publication—it’s a grieving process—but it’s essential to having something in digestible form for the outside world.

And, of course, you may want to try and do more than one publication. For instance, you might report half of your themes in one paper, and then the other half in another paper; or, if you did a mixed methods study, you could split it into quant. and qual. Or you might divide your literature review off into a separate paper, or do a focused paper on your methodology. ‘Salami slicing’ your thesis too much can end up leaving each bit just too thin, but if there’s two or more meaningful chunks that can come of your work, why not?

Finding the right journal

This is one of the most important parts of writing up for publication, and easily overlooked. Novice researchers tend to think that, first, you do all your research, write it up for publication, and then only at the end do you think about who’s going to publish it. But different journals have different requirements, different audiences, and publish different kinds of research; so it’s really important to have some sense of where you might submit it to long before you get to finishing off your paper. That means you should have a look at different journal website, and see what kinds of papers they publish and who they’re targeted towards—and take that into account when you draft your article.

Importantly, each journal site will have ‘Author Guidelines’ (see, for instance, here) and these are essential to consult before you submit to that journal. To be clear, these aren’t a loose set of recommendations for how they’d like you to prepare your manuscript. They’re generally a very strict and precise set of instructions for the ways that they want you to set it out (for instance, line spacing, length of abstract), and if you don’t follow them, you’re likely to just get your manuscript returned with an irritated note from the publishing team. Particularly important here is the length of article they’ll accept. This really varies across journals, and is sometimes by number of pages (typically 35 pages in the US journals), sometimes by number of words (generally around 5-6,000 words)—and may be inclusive of references and tables, etc., or not. So that’s really important to find out before you submit anywhere, as you may find out that you’re thousands of words over the journal’s particularly limit. Bear in mind that, particularly with the higher impact journals (see below), they’re often looking for reasons to reject papers. They’re inundated: rejecting, maybe, 80% of the papers submitted to them. So if they don’t think you’ve bothered to even look at their author guidelines, they may be pretty swift in rejecting your work.

So which journals should you consider? There’s hundreds out there and it can feel pretty overwhelming knowing where to start. One of the first choices is whether to go with a general psychotherapy and counselling research journal, or whether something more specific to the field you’re looking at. For instance, if your research was on the experiences of clients with eating disorders in CBT, you could go for a specialised eating disorders journal, or a specialised CBT journal, or a more general counselling/psychotherapy publication. This can be a hard call, and generally you’re best off looking at the journal sites, as above, to see what kind of articles they carry and whether your research would fit in.

Note, a lot of psychotherapy and mental health journals don’t publish qualitative research, or only the most positivist manifestations of it (i.e., large Ns, rigorous auditing procedures, etc.). It’s unfortunate, but if you look at a journal’s past issues (on their site) and don’t see a single qualitative paper, you may be wasting your time with a qualitative submission: particularly if it’s underlying epistemology is right at the constructionist end of the spectrum. And, if you’re aiming to get your qualitative research published in one of the bigger journals, it’s something you may want to factor in right at the start of your project: for instance, with a larger number of participants, or more rigorous procedures for auditing your analysis.

You should also ask your supervisor, if you have one, or other experienced people in the field, where they think you should consider submitting to. If they’ve worked in that area for some time, they should have some good ideas.

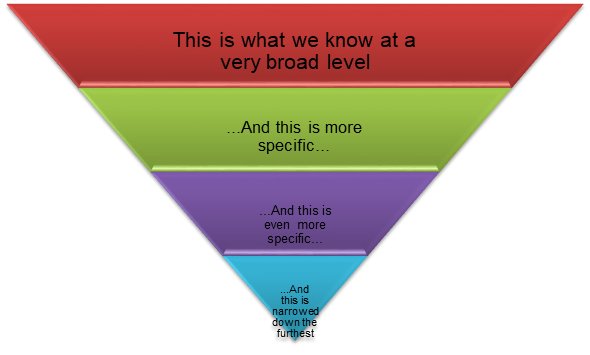

Impact factor

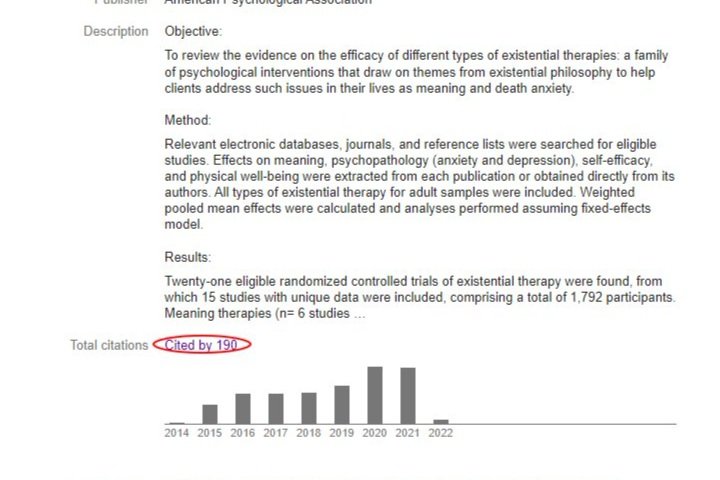

Another important consideration is the journal’s impact factor. This is a number from zero upwards indicating, essentially, how prestigious the journal is. There’s an ‘official’ one from the organisation Clarivate; but these days most journals will provide their own, self-calculated impact factor if they do not have an official one. You can normally find the impact factor displayed on the journal’s website (the key one is the ‘two year’ impact factor—sometimes just called the ‘impact factor’—as against the five year impact factor). To be technical, the impact factor is the amount of times that the average article in that journal is cited by other articles over a particular period: normally two years. So the bigger the journal’s impact factor, the more that articles in that journal are getting referenced in the wider academic field—i.e., impact. The biggest international journals in the psychotherapy and counselling field will have an impact factor of 4 or 5, and ones of 2 or 3 are still strong international publications. Journals with an impact factor around 1 may tend towards a national rather than international reach, and/or be at lower levels of prestige, but still carrying many valuable articles. And some good journals may not have an official impact factor at all: journals have to apply for an official one and in some cases the allocation process can seem somewhat arbitrary.

Of course, the higher the journal’s impact factor, the harder it is to get published there, because there’s more people wanting to get in. So if you’re new to the research field, it’s a great thing to get published in a journal with any impact factor at all; and you shouldn’t worry about avoiding a journal just because it doesn’t have an impact factor, or if it’s fairly low. At the same time, if you can get into a journal with an impact factor of 1 or above that’s a great achievement, and something that’s likely to make your supervisor(s), if they’re co-authors on the paper (see below), very happy. For more specific pointers on publishing in higher impact journals, see here.

These days, the impact of a journal may also be reported in terms of its quartile: so from Q1 to Q4. Essentially Q1 journals are those with impact factors within the top 25% of the subject area, and down to Q4 journals which are in the lowest 25%.

In thinking about impact factor, a key question to ask yourself is also this: Do I want to (a) just get something out there with the minimum of additional effort, or (b) try and get something into the best possible journal, even if it takes a fair bit of extra work. There’s no right answers here: if you have got the time, it’s great if you can commit to (b), but if that’s not realistic and/or you’re just sick and tired of your thesis, then going for (a) is far better than not getting anything out at all.

General counselling and psychotherapy research journals

If you’re thinking of publishing in a general therapy research journal, one of the most accessible to get published in is Counselling Psychology Review – particularly if your work is specific to counselling psychology. The word limit is pretty restrictive though. There’s also the European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy, which is specifically tailored for the publication of doctoral or Master’s research, and aims to ‘provide an accessible forum for research that advances the theory and practice of psychotherapy and supports practitioner-orientated research’. If you’re coming from a more constructionist perspective, a journal like the European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling might also be a good first step, which publishes a wide range of papers and perspectives.

For UK based researchers, two journals that are also pretty accessible are Counselling and Psychotherapy Research (CPR) and the British Journal of Guidance and Counselling (BJGC). Both are very open to qualitative, as well as quantitative studies; and value constructionist starting points as well as more positivist ones. The editors there are also supportive of new writers, and know the British counselling and psychotherapy field very well. See here for an example of a recent doctoral research project published in the BJGC (Helpful aspects of counselling for young people who have experienced bullying: a thematic analysis), and here for one in CPR (Helpful and unhelpful elements of synchronous text‐based therapy: A thematic analysis).

Another good choice, though a step up in terms of getting accepted, is Counselling Psychology Quarterly. It doesn’t have an official impact factor, but it has a very rigorous review process and publishes some excellent articles: again, both qualitative and quantitative.

Then there’s the more challenging international journals, like Journal of Clinical Psychology, Psychotherapy Research, Psychotherapy, and Journal of Counseling Psychology, with impact factors around 3 to 5 (in approximate ascending order). They’re all US-based psychotherapy journals, fairly quantitative and positivist in mindset (though they do publish qualitative research at times), and if you can get your research published in there you’re doing fantastically. Like a lot of the journals in the field, they’re religiously APA in their formatting requirements, so make sure you stick tightly to the guidelines set out in the APA 7th Publication Manual. A UK-based equivalent of these journals, and open-ish to qualitative research (albeit within a fairly positivist frame), is Psychology and Psychotherapy, published by the BPS.

There’s even more difficult ones, like the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology with an impact factor of 4.5, and The Lancet is currently at 53.254. But the bottom line, particularly if you’re a new researcher, is to be realistic. Having said that, there’s no harm starting with some of the tougher journals, and seeing what they say. At worse, they’re going to reject your paper; and if you can get to the reviewing stage (see below), then you’ll have a really helpful set of comments on how to improve your work.

If a journal requires you to pay to publish your article, it’s possible a predatory publisher (‘counterfeit scholarly publishers that aim to trick honest researchers into thinking they are legitimate’, see APA advice here). In particular, watch out for emails, once you’ve completed your thesis, telling you how wonderful your work is and how much they want to publish it in their journal—only to find out later that they charge a fortune for it. You may also find yourself getting predatory requests to present your research at conferences, with the same underlying intent. Having said that, an increasing range of reputable journals—particularly online ones that publish papers very quickly, like Trials—do ask authors to pay Article Processing Charges (APC). Generally, you can tell the ‘kosher’ ones by their impact factor and whether they have a well-established international publisher. It’s also very rare for non-predatory journals to reach out to solicit publications. Check with a research supervisor if you’re not sure, but be very, very wary of handing over any money for publication.

Writing your paper

So you know what you’re writing and who for, now you just have to write it. But how do you take, for instance, your beautiful 30,000 word thesis and squash it down to a paltry 6,000 words?

If you’re trying to go from thesis to article, the first thing is that, as above, you can’t just cut and paste it together. You need to craft it: compiling an integrated research report that is carefully knitted together into a coherent whole. It’s an obvious thing to say, but the journal editors and reviewers won’t have seen your thesis, and they’ll care even less what’s in it. So what they’ll want is a self-contained research report that stands up in its own right—not referring back to, or in the context of, something they’ll never have time to read. That’s particularly important to bear in mind if you’re writing two or more papers from your research: each needs to be written up as a self-contained study, with its own aims, methods, findings, and discussion.

In writing your paper, try and precis the most important parts of your thesis in relation to the question(s) that you’re asking. Take the essence of what you want to say and try and convey it as succinctly and powerfully as possible. Think ‘contracting’ or ‘distilling’: reducing a grape down to a raisin, or a barley mash down to a whiskey—where you’re making it more condensed but retaining all the goodness, sweetness, and flavour. That doesn’t mean you can’t cut and paste some parts of your thesis into the paper, but really ask yourself whether they can be condensed down (for instance, do you really need such long quotes in your Results section?), and make sure you write and rewrite the paper until it seamlessly joins together.

Your Results are generally the most important and interesting part of your paper, so often the part you’ll want to keep as close to its original form as possible. So if you’ve got, say, 7,000 words for your paper, you may want your Results to be 2-3,000 of that (particularly if it’s qualitative). Then you can condense everything else down around it. Your Introduction/Literature Review may be reducible to, perhaps, 500-1,000 words. Maybe 1,000 words for your Methods and Discussion sections; 1,000 words for References.

If you’ve written a thesis, you may be able to cut some sections entirely. If you’re submitting to a more positivist journal, your reflexivity section can often just go; equally your epistemology. Sorry. If your study is qualitative, you may also find that you can cut down a lot of the longer quotes in your Results. Again, try and draw out the essence of what you are trying to say there… and just say it.

Generally, and particularly for the higher-end US journals, you’re best off following the structure of a typical research paper (and often they require this): Background, Method, Results, Discussion, References. They’re may be more latitude with the more constructionist journals but, again, check previous papers to see how research has been written up.

Make sure you write a very strong Abstract (and in the required format for the journal). It’s the first thing that the editor, and reviewers, will look at; and if it doesn’t grab their attention and interest then they may disengage with the rest. There’s some great advice on writing abstracts in the APA 7th Publication Manual as well as on the internet (for instance, here).

Supervisors and consultants

If you’ve had a supervisor, or supervisors, for your research work, there’s a question of how much you involve them in your publication, and whether you include them as co-author(s). At many institutions, there’s an expectation that, as the supervisor(s) have given intellectual input into the research, they should be included as co-author(s), though normally only as second or third in the list. An exception to the latter might be if a student feels like they don’t want to do any more work at all after they’ve submitted their thesis, in which case there might be an agreement that one of the supervisors take over as first author. Here, as with any other arrangement, the important bit is that it’s agreed up front and everyone is clear about what’s involved.

Just to add, as a student, you should never be pressurised by a supervisor into letting them take the first author role. I’ve never seen this actually happen, but have heard stories of it; and if you feel under any coercion at all then do talk to your Course Director or another academic you trust.

The advantage of keeping your supervisor(s) involved is that they can then help you with writing up for publication, and that can be a major boost if they know the field and the targeted journal well. So use them: probably, the best way of getting an article published in a journal is by co-authoring it with someone who’s already published there. A way that it might work, for instance, is that you have a first go at cutting down your thesis into about the right size, and then the supervisor(s) work through the article, tidying it up and highlighting particular areas for development and cutting. Then it comes back to you for more work, then back to your supervisor(s) for checking, then back to you for a final edit before you submit.

One final thing to add here: even though you may be working with people more senior and experienced to you, if you are first author on the paper, you need to make sure you ‘drive’ the process of writing and revising, so that it moves forward in a timely manner. So, for instance, if one of your supervisors is taking a while to get back to you, email them to follow up and see what’s happening; and make sure you always have a sense of the process as a whole. This can be tough to do, given the power relationship that would have existed if you were their supervisee; but, in my experience, the most common reason that efforts at publication fizzle out are because there’s no one really ‘holding’ or driving the process: no one making sure it does happen. Things fall through gaps: a supervisor doesn’t respond for a month or two, no one follows them up, the other supervisor wanders off, the student gets on with other things… So spend a bit of time, at the start, agreeing who’s going to be in charge of the process as a whole (normally the first author) and what roles other authors are going to have. And, if it’s agreed that you are in the driving seat, you’ve got both the right and the responsibility to follow up on people to make sure it all gets done.

How do you submit?

That takes us to the process of submitting to a journal. So how does it work? Nearly all journals now have an online submission portal so, again, go to the journal website and that will normally take you through what you need to do. Submission generally involves registering on the site, then cutting and pasting your title and abstract into a submission box, entering the details of the author(s) and other key information, and uploading your papers. The APA 7th Manual has some great advice on how to prepare your manuscript so that it’s all ready for uploading (or see here), and if you follow that closely you should be ok for most journals.

You also normally need to upload a covering letter when you submit, which gives brief details of the paper to the Editor. This can also cover more ‘technical’ issues, like whether you have any conflicts of interest (have you evaluated, for instance, an organisation that you’re employed by?), and confirmation of ethical approval. If you’ve submitted, or published, related papers that’s also something you can disclose here. Generally, it’s fine to submit multiple papers on different aspects of your thesis, but they should be different; and it’s always good just to let the editor know so that it doesn’t come as a surprise to them later.

Note, you definitely mustn’t submit the same paper (or similar papers) to more than one journal at any one time. That’s a real no-no. Of course, if your paper gets rejected it’s fine to try somewhere else (see below), but you could get into a horrible mess if you submitted to more than one journal in parallel (for instance, what happens if they both accept it?). So most journals ask you, on submission, to confirm that that’s the only place you’ve sent it to and that’s really important to abide by.

What happens then?

The first thing that normally happens is that a publishing assistant will then have a quick look over your article to check that it’s in the right format. As above, they can be pretty pernickety here, and if you’re over the word limit, or not doing the right paragraph spacing, or even indenting your paragraphs when you shouldn’t, you can find your article coming back to you asking for formatting changes before it can be considered. So try and get it right first time.

Then, when it’s through that, it’s normally reviewed by the journal editor, or a deputised ‘action editor’. Here, they’re just getting a sense of whether the article is right for the journal, and at about the required level. Often papers will get rejected at that point (a desk rejection), with a standard email saying that they get a lot of submissions, they can’t review everything, it’s no comment on the quality of the paper, etc., etc. Pretty disappointing—and generally not much more feedback than that. Ugh!

If you don’t hear from the journal a week or so after submission, it generally means it’s then got through to the next stage, which is the review process. Here, the editor will invite between about two and four experts in the field to read the paper, and give their comments on it. This process is usually ‘blind’ so they won’t know who you are and you won’t know who they are. In theory, this helps to keep the process more ‘objective’: the reviewers aren’t biased by knowing who you actually are, and they don’t have to worry about ‘come back’ if they give you a bad review.

The review process can take anything between about three weeks and three months. You can normally check progress on the journal submission website, where it will say something like ‘Under review.’ If it gets beyond three months or so, it’s not unreasonable to write to the journal and ask them (politely) how things are going. But there’s no relationship between the length of the time of the review and the eventual outcome—it’s normally just that one of the reviewers is taking too long getting back to them, and they may have had to look elsewhere. Note, even if it is taking a long time and you’re getting frustrated, you can’t send the paper off somewhere else until things are concluded with that first journal. You could withdraw the paper, but that’s fairly unusual and mostly people wait until the reviews are eventually back.

The ‘decision letter’

Assuming the paper has gone off for review, you’ll get a decision letter email from the editor. This is the most exciting—but also the most potentially heartbreaking part—of the publication process: a bit like opening the envelope with your A-level results in. Generally, this email gives you the overall decision about acceptance/rejection, a summary from the editor of comments on your paper, and then the specific text of the reviewers’ comments.

In terms of the decision itself, the best case scenario is that they just accept it as it is. But this is so rare, particularly in the better journals, that if you ever got one (and I never have), you’d probably worry that something had gone wrong with the submission and review process.

Next best is that they tell you they’re going to accept the paper, but want some revisions. Here, the editor will usually flag up the key points that they want you to address, and then you’ll have the more specific comments from the reviewers. Sometimes, journals will refer to these as ‘minor revisions’, as opposed to more ‘major revisions’, but often they don’t use this nomenclature and just say what they’d like to see changed. Frequently, they don’t even say whether the paper has been accepted or not—just that they’d like to see changes before it can be accepted—and that can be frustrating in terms of knowing exactly where you stand. Generally, though, if they don’t explicitly use the ‘r’ word (‘reject’), it’s looking good.

Then you can get a ‘reject and resubmit’. Here, the editor will say something like, ‘While we can’t accept/have to reject this version of the paper, due to some fairly serious issues or reservations, we’d like to invite you to resubmit a revision addressing the points that the reviewers have raised’. In my experience, about 60% of the time when you resubmit a rejected paper you eventually get it through, and about 40% of the time they subsequently reject it anyway. The latter is pretty frustrating when you’ve done all that extra work, but at least you’ve had a chance to rework the paper for a submission elsewhere.

Then, there’s a straight rejection, where the editor says something fairly definitive like, ‘…. your paper will not be published in our journal.’ That’s pretty demoralising but, at least, if you’ve got to this stage, you’ve nearly always got some very helpful feedback from experts in this field to help you improve your work.

Emotionally, the editorial and reviewing feedback can be pretty bruising, especially when it’s a rejection. Reviewers don’t tend to pull punches: they say what they think—particularly, perhaps, because they’re under the cover of anonymity. So you do need to grow a fairly thick skin to stick with it. Having said that, a good reviewer should never be diminishing, personal, or nasty. Even when rejecting a submission, they’ll be able to highlight strengths as well as limitations, and to encourage the author to consider particular issues and pursue particular lines of enquiry, to make the best of their work and their own academic growth. So if something a reviewer says is really hurtful, it’s probably less about the quality of your work, and more about the fact that they’re being an a*$e (at least, that’s what I tell myself!).

Most journals do have some kind of appeal process if you’re really unhappy with the decision made. But you need a good, procedural argument for why you think the editorial decision was wrong (for instance, that it was totally out of step with the actual reviews, or that the reviewers hadn’t actually read your paper) and, in my experience, appeals don’t tend to get too far. However, I have heard of one or two instances of successful outcomes.

By the way, sometimes, quite quickly after you’ve started to submit papers (and possibly even before), you may be asked to review for the journal yourself. That can be a great way of getting to know the reviewing process better—from the other side. It’s also part of giving back to the academic community: if people are spending time looking at your work, it’s only fair you do the same. So do take up that opportunity if you can. There’s some very helpful reviewer guidelines here.

Revising and resubmitting

If you’re asked to make revisions, journals will generally give you six months or so—less if they’re relatively minor. Here, it’s important to address every point raised by each of the reviewers. That doesn’t mean you have to do everything they ask for, but you do have to consider each point seriously, and if you disagree with what they’re saying, you need to have a good reason for it. Generally, you want to show an openness to feedback and criticism, rather than a defensive or a closed-minded attitude. If the editor feels like they’re going to have to fight with you on each point, they might just reject the paper on resubmission.

As well as sending back the revised papers, you’ll need to compile a covering letter indicating how you addressed each of the points that the reviewers’ raised. You may want to do this as a table as you go along: copy-pasting each of the reviewers’ points, and then giving a clear account of how you did—or why you did not—respond to that issue.

Pay particular attention to any points flagged up by the editor. Ultimately it will be their decision whether or not to accept your paper, so if they’re asking you to attend to some particular issues, make sure you do so.

Resubmissions go back through the online portal. If the changes required are relatively minor, it may just be the editor looking over them; anything more substantive and they’ll go back to the reviewers again for comment. Bear in mind that the reviewers are often the original ones who looked at your paper, so ignore their comments at your peril.

It’s not unusual to have three or four rounds of this review process: moving, for instance, from a ‘revise and resubmit’ to ‘major revisions’ to ‘minor changes’. At worst, it can feel petty and irritating; but, at best, and far more often, it can feel like a genuine attempt by your reviewers to help you improve the paper as much as possible. The main thing here is just to be patient and accept that the process can be a lengthy one. If you’re in a rush and just desperate to get something out whatever it’s quality, you’re likely to be profoundly frustrated—unless you’re prepared to accept publication in a journal of much lower quality.

Once it’s accepted

Yay! You got there! That’s it… not quite. It’s brilliant to have that final acceptance letter from the journal telling you that they’ll now go ahead and publish your paper, but there is still a little more to do. A few weeks after the acceptance email, they’ll send you a link to a proof of the paper, where there’ll be various, relatively minor copy-editing corrections and queries. For instance, they may suggest alternate wording for sentences they think could be improved, or ask you to provide the full details for a reference. Sometimes, this may be in two stages: with, first, a copy-edited draft of your manuscript, and then a fully formatted proof). Note, at this point, they really don’t like you to make any substantive changes, so anything you want to see in the final published article should be there in your final submitted draft.

Then that it is. Normally the paper will be out, online, a week or so after that. And once it is, you can finally celebrate, but do also make sure you let people know about the paper, and give everyone the link via social media. The journal, itself, are unlikely to do any specific promotion of the article, so it’s up to you to tell colleagues about it and encourage them to let others in the field know.

Open Access?

Although it’s great you’ve got your paper out, the final pdf version may only be available to people who have access to the journal. So students at higher education institutes are likely to be fine, as are colleagues working for large organisations like the NHS, but what about counsellors or psychotherapists who don’t have online access, and where the cost of purchasing single articles are often prohibitively high? One possibility is that you (or the institution you are affiliated to) can pay to make your article ‘open access’. However, this can cost £1000s (unless the University has a pre-established agreement with the publisher) and is not something most of us can afford.

Fortunately, journals normally allow you to post either your original submission to the journal (an ‘author’s original manuscript’, or ‘preprint’ version of your article), or your final submission (a ‘prepublication’, ‘author final’, ‘postprint’, or ‘author accepted manuscript’ version of your article) on an online research depository, such as ResearchGate. Policies vary, so check the specific policies for the journal that published your paper:

This version of your paper won’t be the exact article that you published, and it won’t have the correct pagination etc., but if you prepare it well (see an example, here), then it means that those who don’t have access to journal sites can still find, read, and cite your research. Different journals do have different policies on this, though, so make sure you check with the specific publisher of your journal before making any version of your paper publicly available. Generally, what the publishers are very vigilant about is the making available, in a public place, of the final formatted pdf of your paper (unless, as above, it’s specifically open access).

Trying elsewhere

If your paper gets rejected, your choices are (a) just to give up, (b) resend the paper as is it somewhere else, or (c) make revisions based on the feedback and then resubmit elsewhere. There’s also, of course, a lot of grey areas between (a) and (b) depending on how many changes you feel willing—and able—to make. Generally, if you can learn from the feedback and revise your paper that’s not a bad thing, and can help form a stronger submission for next time. Of course, it is always possible that the next set of reviewers will see things in a very different way; and sometimes changes made to address one set of concerns will then be picked on by the next set of reviewers as problems in themselves. As for (a), well, I promise you this: if the research is half-decent, then you can always get it published somewhere. Bear in mind that, as above, if you’ve been awarded a doctorate for your research (and, to some extent, a Master’s), it’s publishable by definition.

Generally, when people get their papers rejected, they move slowly down the impact hierarchy: so to journals that might be more tolerant of the ‘imperfections’ in your paper. But there’s no harm in trying journals at a similar level of impact when you’re trying somewhere else or even higher up—particularly when you really don’t agree with the rejecting journal’s feedback.

Ultimately, it’s about persistence. To repeat: if you want to get something published, and it’s passed at doctoral (or, often, Master’s) level, you will. But it needs resilience, responsiveness, and a willing to put up with a lot of knockbacks.

Other pathways to impacts

Journals aren’t the only place where you can get your research out to a wider audience and make an impact. For instance, you could write a synopsis of your thesis and post it online: such as on Researchgate. You won’t get as big a readership as in an established journal, but at least it will be more accessible than your university library, and you can tell people about it via social media. Or you could do a short blog about your research, or make a video, or talk to practitioners and other stakeholders about your work. If you want to make your research findings widely accessible to practitioners, you could also write about them for one of the counselling and psychotherapy magazines, like BACP’s Therapy Today or BPS’s The Psychologist.

There’s also many different conferences that you can go to to present your findings: as an oral paper, or simply as a poster. Two of the best, for general counselling and psychotherapy research in the UK, are the annual research conference of the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP), and the annual conference of the BPS Division of Counselling Psychology (DCoP). Both are very friendly, encouraging, and supportive; and you’ll almost certainly receive a very warm welcome just for having the courage to present your work. At a more international level is the annual conference of the Society for Psychotherapy Research (SPR). That’s a great place to meet many of the leading lights in the psychotherapy research world, and is still a very friendly and supportive event.

You can also think about ways in which you might want your work to have a wider social and political impact. Would it make sense, for instance, to send a summary to government bodies, or commissioners, or something to talk to your local MP about?

Of course, this could all be in addition to having a publication (rather than instead of it), but the main point here is that, if you want your research to have impact, it doesn’t just have to be through journal papers.

To conclude…

When you’ve finished a piece of research—and particularly a long thesis—often the last thing you’ll want to be doing is reworking it into one or more publications. You can’t stand the sight of it, never want to think about it again—let alone take the research through a slow and laborious publication process. But the reality is, as people often say, the longer you leave it the harder it gets: you move away from the subject area, lose interest; and if you do want to publish at a later date, you’ll have to familiarise yourself with all the latest research (and possibly without a library resource to do so). So why not just get on with it, get it out there; and then you can have your work, properly, in the public domain, and people can use it and learn from it, and improve what they do and how they do it. And then, instead of spending the next few decades wishing you had done something with all that research, you can really, truly, have the luxury of never having to think about it again.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Jasmine Childs-Fegredo, Mark Donati, Edith Steffen, and trainees on the University of Roehampton Practitioner Doctorate in Counselling Psychology for comments and suggestions.

Further Resources

There is a great, short video here from former University of Roehampton student, Dr Jane Halsall, talking about her own experience of going from thesis to published journal paper. Jane concludes, ‘You’re doing something for the field, and you’re doing something for the people who have actually taken the time out to participate. So be encouraged, and do do it.’

An accessible set of tips on publishing in scholarly is also available from the APA:

Disclaimer

The information, materials, opinions or other content (collectively Content) contained in this blog have been prepared for general information purposes. Whilst I’ve endeavoured to ensure the Content is current and accurate, the Content in this blog is not intended to constitute professional advice and should not be relied on or treated as a substitute for specific advice relevant to particular circumstances. That means that I am not responsible for, nor will be liable for any losses incurred as a result of anyone relying on the Content contained in this blog, on this website, or any external internet sites referenced in or linked in this blog.