A video based on this blog filmed with Rory at Counselling Tutor

Aims

The purpose of a literature review is to bring together what is known, so far, in relation to the question(s) being asked. So, for a decent literature review, the first thing is to be really clear about its aims and the questions you are asking (see Research aims and questions: Some pointers).

A literature review is not an essay. When people write an essay, what they generally do is to draw together various bits of theory and research to try and make one (or several) points. An essay is about constructing an argument and then justifying it. But a literature review is different. You’re not trying to make a point in it or prove something you already believe in. Rather, you’re asking a question and then trying to answer it by searching out all the relevant literature in relation to that question. If you know the answer to your question(s) before you’ve done your literature review then something is not quite right. A literature review, as with all research, should be based on answering a question you don’t know the answer to.

The Scope of a literature review

From degree level to Master’s level to doctoral level (Levels 6, 7, and 8, respectively, in the QAA Frameworks for Higher Education Qualifications), a literature review should demonstrate a systematic understanding of some element of a particular field. In addition, from Master’s to doctoral level, this should be increasingly at the forefront of a discipline and creating original knowledge; and, at doctoral level, meriting journal publication. To achieve all this, it means that your research question(s) needs to be focused and narrow enough to allow for a systematic understanding. If there’s too much literature on your question to know it all, your question is probably too broad—try narrowing it down.

Ask yourself, ‘What might I feel confident in saying that I systematically understand, that I can be a leading expert on?’ If that feels way above what you can achieve, narrow your focus down until it’s really possible for you to believe you’re a leading expert in it. So, for instance, if you’re asking a question like, ‘What is the relationship between empathy and therapeutic outcomes?’ you’ll soon find out that it’s going to take a lifetime to lead expertise here: there’s hundreds of research papers on it. But the relationship between self-disclosure and therapeutic outcomes in person-centred therapy—there’s maybe a dozen or so key papers here that means that some level of leading expertise is within your grasp.

Remember—particularly for Master’s and doctoral level—you also need to be at the forefront of a field. Not what was talked about 20 years ago, but what is being discussed and debated now. If you find most of your references are back in the 1980s and 1990s, think about why there’s nothing more current. Is it that people have stopped being interested in this question? Is it that you’ve missed the latest research?

At Master’s level, you need to demonstrate mastery of a field. That is, not just that you know the literature, but that you can do things with it: e.g., evaluate the reliability of different sources of evidence, compare, and contrast ideas. At doctoral level, you should be able to demonstrate, not only mastery, but an ability to do things with the literature in independent and original ways: e.g., come up with new interpretations and perspectives. So at both Master’s and doctoral level, you need to be able to go beyond simply describing relevant literature or findings, towards producing a synthesised understanding of the current state of knowledge in relation to your research questions.

Be critical. This doesn’t mean insulting or attacking specific pieces of work—e.g., ‘What a tw*t Smith (2007) is for saying…’—and it doesn’t mean finding flaws in research for the sake of it. What it means is being able to extract from the literature what is relevant to your own research question(s), and to evaluate its importance to you. That might mean, for instance, saying that the participants in a particular study were all White, so the findings may not be generalisable to people of other ethnicities; or that the use of quantitative methods means that we don’t really understand the mechanisms of change.

It’s not the end of the world if there’s one or two or papers that you’ve missed. Everyone misses things, and your examiners/assessors are likely to understand. But try to avoid having big gaps in your review, where whole areas of literature have been overlooked. That’s where systematic reviews can really come in handy.

doing a literature review systematically

Systematic literature reviews are reviews of the literature that have a series of explicitly-stated stages. This might include specifying your search terms, reporting on your ‘hits’, and systematically analysing your findings. They also focus on answering an explicitly-stated question. Different teaching programmes have different requirements about whether a literature review should be ‘systematic’ or not but, often, it’s an indication of higher quality, robustness, and transparency. However, there’s not one form of a systematic literature review and, in general, it can be considered on a spectrum: from highly systematic reviews (including, for instance, multiple coders, see below), to reviews with some systematic elements (such as an explicitly-articulated search strategy). A literature review may also have one or more systematic sections, rather than being a systematic literature review in its entirety. For instance, you might start a literature review by exploring a particular area, identify a question that seems of importance, and then go on to conduct a systematic review of what is known in relation to that question.

Ideally, the stages of a systematic literature review are set out before you start as a written protocol. You can see an example of one here, which we developed to examine the factors that facilitated and inhibited integration in child mental health services (see published paper here). This protocol covers such areas as:

Aims

Eligibility criteria for studies (i.e., which studies you’ll accept for review)

Study characteristics (e.g., only empirical studies, only studies of young people)

Report characteristics (e.g., only studies after 1990, only English language)

Information sources (i.e., where you’ll look for studies, see below)

Study selection procedures

Planned method of analysis

Feel free to use the headings from our protocol for your own review.

There’s a very well-established set of guidelines that set out standards and expectations for reviews (particularly quantitative ones), the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). All the elements detailed here aren’t normally considered necessary for a Master’s or doctoral level review, but even if you don’t do a full systematic review, you may want to draw on certain parts (such as a ‘flow chart’ of the references you used, see below).

At minimum, for any kind of literature review, it is generally useful to show how you went about ensuring that you identified relevant literature in your area. For instance, you could include your search terms, and information about the databases searched, in your Appendix). Probably what’s most important is to show that your literature search, and write-up, weren’t just ad hoc. That is, that you didn’t just ‘cherry pick’ certain bits of literature, or arbitrarily select the papers from a five minute search of Google Scholar. However, you do it, you want to make it clear that you conducted a systematic, comprehensive, and meaningful review of the field: one that gave you the best chance of answering your own research question(s) to the fullest.

Study selection procedures

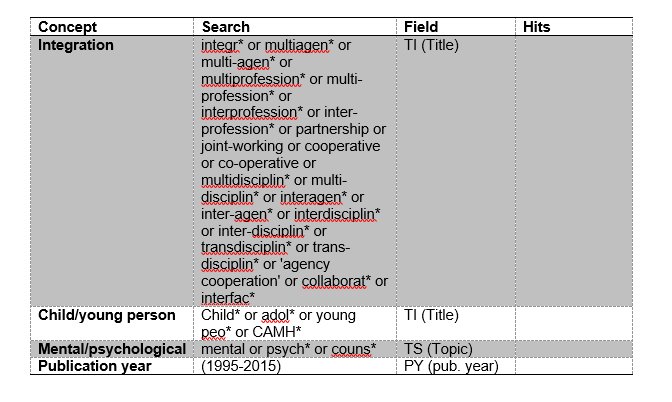

Generally, the best way to start finding articles for review is by setting out the different concepts within your study (for instance, as a table), and then brainstorming all the different terms that might be used to cover those concepts. For instance, if you were doing a review of research on person-centred therapy and autism, you might develop one set of terms for research (e.g., ‘empirical’, ‘study’, ‘evidence’…), one set for person-centred therapy (e.g., ‘person-centred’, ‘client-centred’, ‘client-centered’…), and one set for autism (e.g., ‘autism’, ‘asperger’s’, autistic…). To begin with, try and generate as many relevant terms as possible, and don’t forget that you want to include US-spelling as well as UK-spelling (like ‘person-centred’ and ‘person-centered’). Different search engines have different ‘wild cards’ that you can use (like * or $), which is where you specify just part of the word. For instance, if you want to search texts with ‘counselling’, ‘counsellor’, ‘counseling’, ‘counselor’, ‘counselled’, etc., you may be able to just use ‘counsel*’ (check the help sites on the specific search you are using). Importantly, you’ll also need to select the field that you want to search in. For instance, do you want to find sources with this term in the title, the abstract, or anywhere in the text—different field selections will give very different sets of results.

Below is an example of the search strategy that we used for our paper on interagency collaboration in child mental health services. You can see that we searched for terms about integration, and then also about children/young people, and mental issues. They needed to be post-1995 (and the study was conducted in 2015). The asterixes are wild cards that we used to ensure we didn’t miss terms with slightly different endings.

Example search strategy for review of integration in child mental health services

Although, ideally, this search strategy is set out before you do your search, it is inevitably going to be an iterative process: moving between testing out particular strategies, seeing how many hits you get, then revising the strategy to either broaden or narrow down the number of hits. For instance, you might start with a search that has ‘child*’ anywhere in the text, but because you get tens of thousands of hits, you revise this to require ‘child*’ to be in the title. As you start to see your hits, you may also want to include additional search terms for your concepts.

Very approximately, you want to find a search strategy that gets you, initially, something like 200 to 2000 hits. More than that becomes unmanageable. Less than that and you’re possibly missing some key articles. What you then do is to go through all the titles, or maybe the titles and abstracts, and identify just those that seem relevant to your review. Inevitably you’ll reject the majority of your hits: for instance, they might not be empirical papers, or they might use the term ‘person-centred’ to mean something entirely different from what you are looking at. That will then leave you with a smaller number of articles where you then might read through the whole paper to see if the article is relevant. Again, when you do that you’ll end up excluding a lot of your papers.

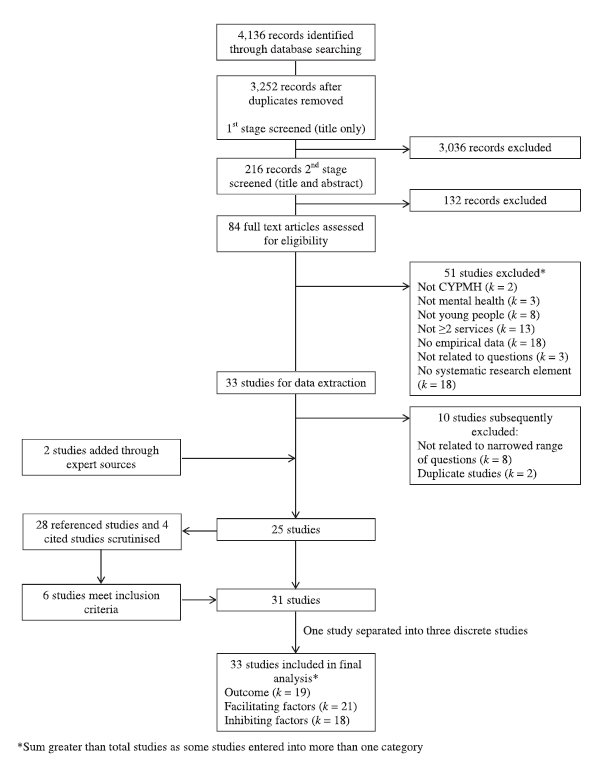

Ideally, particularly at Master’s and doctoral level, you should be keeping track of all the hits/articles you are reviewing and selecting/excluding at each stage. The ideal way to present that is through a Study flow diagram. Below is an example of such a diagram from our study of integration in child mental health services. You’ll see that there were a number of stages, and we explicitly state why we excluded certain papers. This level of detail may only be needed for doctoral or journal publishing level, but at any level you can use even a simple flow diagram to show key elements in the study selection process.

Example study flow diagram for review of integration in child mental health services

Just to add, at publishable level (and, ideally, at doctoral level), it’s good to be able to show some degree of ‘inter-rater reliability’ in the study selection process. What this means is that the selections made were not just down to the particularities of the individual researcher, but would be replicable across different researchers. The way that you do this is to have someone else (say a course colleague) do some of the selection process to, and then see how much similarity there was across selections. For instance, based on reading the full papers, what proportion of papers that you identified as eligible did a colleague also identify as eligible? If that’s less than, say, 50% or so, it suggests that there’s a lot of individual variation in what would be considered eligible for your review, and the criteria may need some tightening up.

If you know there are papers that are relevant to your review but aren’t coming up through your search strategy, that means there’s something wrong with the strategy. Have a look at why it’s not picking up those key papers and revise the strategy accordingly: if it’s missing those papers, it’s also possibly missing other papers that are important to your review. At the end of the day, saying ‘Well, I excluded Papers X and Y because they didn’t come up in my search strategy,’ isn’t enough. Your search strategy should be a tool for finding relevant texts, not the criteria, per se, of what is or is not relevant.

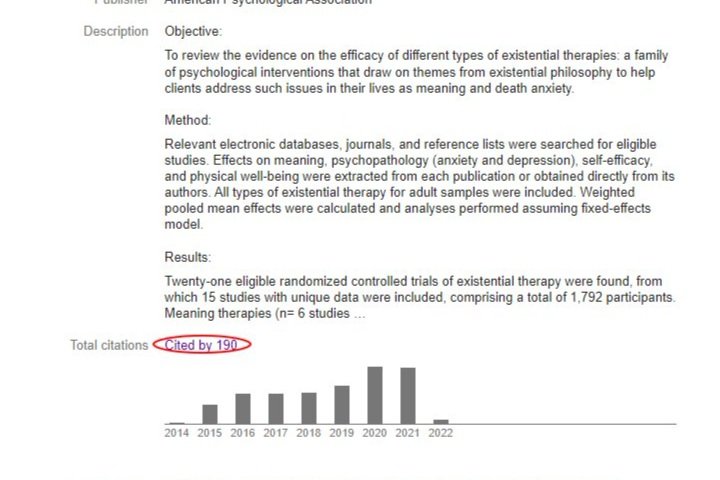

As well as using search engines, a key source to draw on is the reference list in the articles that you have found. Citation searches reverse that process, and can also be extremely helpful. In a citation search, you take key articles and then look at the subsequent articles that have referenced that article. That way, you find the very latest research related to that work. To do a citation search, you simply find the key article on a database and then click on the ‘citations’ link (or in Google Scholar, ‘Cited by…’). You can see this circled in red on the screenshot below:

Example ‘Cited by’ hyperlink in Google Scholar

By the end of this study selection process, you want to end up with somewhere between about five and 30-40 papers for inclusion in your review. More than that and you may well struggle to meaningfully integrate the findings. Less than that and your review is going to be more and more simply a re-statement of what the papers found. But if you’ve asked a really important, meaningful question, conducted a really thorough search, and then just found there isn’t anything out there—or only one or two studies—that can be a meaningful outcome in itself. Importantly, too, don’t take it as a sign of personal failure if you haven’t found any literature out there. The reality is, on a lot of counselling- and psychotherapy-related questions, there just isn’t much research. But identifying that can be really helpful in letting the field know areas to focus on for future.

Information sources

This may depend on the databases that your institution has access to. At minimum, you would ideally want to search Web of Science and PsychInfo, two of the principal sources for psychology-related papers. Google Scholar makes a useful addition to this: it can help you identify a different range of papers, more of the ‘grey’ literature. Don’t worry too much about your university or college library: that’s inevitably going to have a relatively limited array of books and journals.

How do I make my case?

As emphasised earlier, if you’re thinking, ‘How do I construct an argument so that I can show that I’ve got some good ideas here?’ you may be asking the wrong question for a literature review. That’s fine for an introductory section of a thesis—showing why your question is of importance and relevance—but, as above, the aim of a literature review is to provide a balanced review of what we know so far in relation to a particular question, not to convince the reader of something. So if the structure of your literature review goes something like, ‘Well x is really important, and so is y, and that means z is likely [and so I’m going to do some research now to show it is]’ you may need to backtrack. Remember, ask yourself, ‘What is it that I don’t know that I am trying to find out?’ Trying to prove a point is never a great basis for a piece of research.

Format of the write-up

In most cases in the counselling and psychotherapy field, reviews will be of a qualitative nature (i.e., written up in words)—and that’s what I’ll address here. There are also reviews that mathematically combine data, known as meta-analysis. These have their own particular methods (see, for instance, Practical meta-analysis) and are best conducted using dedicated software, such as Comprehensive Meta-analysis.

Use headings and subheadings in each of the sections to keep a clear structure to the paper, and make sure that the hierarchy of these headings is clear to the reader: i.e., make the higher level headings bigger, bolder, etc. as compared with lower order headings. Some pointers on formatting and presenting your work are available here.

You will probably want to start your literature review with a short section detailing the method by which you went about your literature search. Even if you didn’t use a systematic method throughout, it’s worth saying something of how you searched the literature, so that the reader has a sense of what you might have found—and missed.

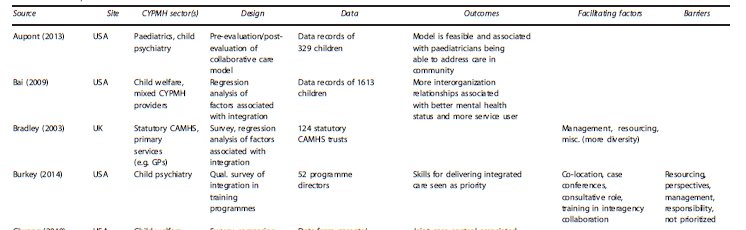

A table of the final articles that you included in your review can be really helpful, either at the start of the review or as an appendix. Each paper can be a row, and then you can have various key features in the columns, such as the location of the study, the number of participants, key findings, etc. An example—the first few rows from our review of integration in child mental health services—is below.

Example table of studies for review of integration in child mental health services

Try to avoid ‘laundry list’ reviews: ‘stringing together sets of notes on relevant papers’ (McLeod, 1994, p.20) one after another. For instance:

Smith (1992) found that…..

And Brown (2011) found that…

And Jones (1996) found that…

And then Patel et al. (2001) found that…

Or narrative/historical version of a laundry list review: For instance:

First, Smith (1992) found that…..

Then Jones (1996) found that…

Then Patel et al. (2001) found that…

Then Brown (2011) found that…

Remember that, particularly at Master’s and doctoral level, a literature review is not just about précising previous research in the field: providing summaries of what lots of different studies said. It’s about drawing the research together in coherent and meaningful ways.

So wherever possible, adopt a thematic style of review. ‘This strategy involves the identification of distinct issues or questions that run through the area of research under consideration. Thematic literature reviews enable the writer to create meaningful groupings of papers in different aspects of a topic. This is therefore a highly flexible style of review, in which the complex nature of work in an area of area can be respected while at the same time bringing some degree of order and organisation to the material’ (McLeod, 1994, p.20). In a thematic review, it is likely that several different sources will be cited in one paragraph.

Some research has shown A… (Jones, 1996; Smith, 1992)

But other research has shown B (Patel et al., 2001; Jones, 1996), although there are some problems with these findings (Grey et al., 1990).

More broadly, we know that Z… (White and Brown, 2001; Yellow, 2010).

And there is also some research to suggest X (Blue, 2003; Grey, 1994).

What we know so far, then, is that A seems very likely, and that is supported by Z and X, though B raises some problems about this.

When you review the literature, you don’t need to ascribe every study equal weight and space. Indeed, if you are, it probably suggests you’re being too descriptive and not discriminating enough. Some of the studies you look at will be spot-on relevant to your own research, some only tangentially so. So if you’re extracting what’s really most meaningful to your own questions, you should be taking a lot more from some sources than others. You’re not reviewing to make all these authors feel like they’re being paid due regard. You’re reviewing to take what you need from their work to say what we currently know in relation to your question(s). If content isn’t relevant, leave it out. If it’s highly relevant, say a lot about it.

A thematic approach really allows you to show a high-level, synthesised understanding.

Whenever you make claims about how things are (for instance, ‘empathy is a key factor in therapeutic outcomes’), you must always provide some reference for this.

Make sure you explicitly state somewhere, either at the end of the literature review or in your design, what the main aims/objectives of your study are, and, if relevant, your hypothesis/hypotheses.

Wherever possible, go back to the original sources and reference those, rather than ‘cited in….’ Citations never looks great—that you haven’t bothered to consult the original sources. If you really can’t access the original source (e.g., it’s in another language, or out of publication and unavailable), that’s fine, but use citations sparingly. And be really careful not to take references from a secondary source and cite them as if you have read them: find out what the original authors really said.

EVIDENCE or theory?

Your literature review might be of evidence in relation to a particular question: for instance, ‘How do clients experience person-centred therapy?’ Alternatively, it might be of theoretical propositions: for instance, ‘What is a relational psychodynamic theory of development?’ It could also combine evidence and theory, for instance, ‘What is the relationship between alliance and outcomes for young people?’ There’s no right or wrong here—it is entirely dependent on your question.

What is important, however, is to be clear about when you’re reviewing theory and when you’re reviewing evidence. So, when you write up your review, try not to mix up theoretical statements like, ‘Rogers hypothesised that….’ with empirical statements like, ‘Greenberg et al. found that…’ What someone thinks (even if it was Carl Rogers!), and what someone actually found, are quite separate things. So if you are covering both in your review, it may be an idea to write them up as separate sections.

Just to note, also be careful about mixing up primary studies (e.g., specific pieces of empirical research), with reviews or ‘meta-analyses’ of the field. For instance, you may find through your search strategies a number of papers which review primary studies in relation to a particular question. That’s great, but then use that review to identify the primary studies, and include or exclude those primary studies in your review, as appropriate. You could then note the reviews papers in your introduction, and say about how your review is different. Alternatively, you could do a review of reviews in a field—if there’s a logic in bringing them together and it would be redundant to replicate the review process. But, again, don’t mix that up with a review of primary studies—do one or the other, and be clear about which it is.

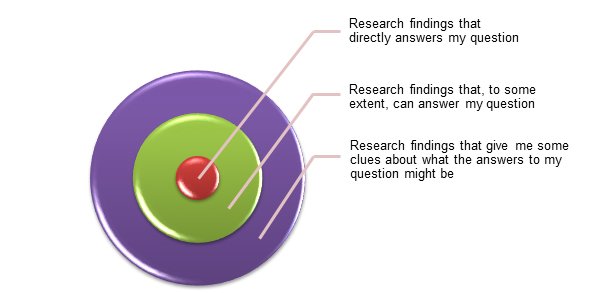

The 'target' approach to structuring your literature review

One way to think about structuring your literature review is like a ‘target’. Start with the evidence that is most relevant to your research question (and perhaps do a systematic review of it). Then what else might be most closely relevant? For instance, if you’re doing a study on negative experiences of young people in person-centred therapy, you’d want to start by looking comprehensively for everything on that specific question. But if there’s not much, then you could review the research on negative experiences of young people in other therapies, then negative experiences of adults in person-centred therapy. The more literature there is at the ‘bullseye’ of your target, the less you need to go broader. But if there’s really not much (and that’s fine), then broaden out to literature from which we might be able to extrapolate potential answers to your question(s).

Target approach to writing up a literature review

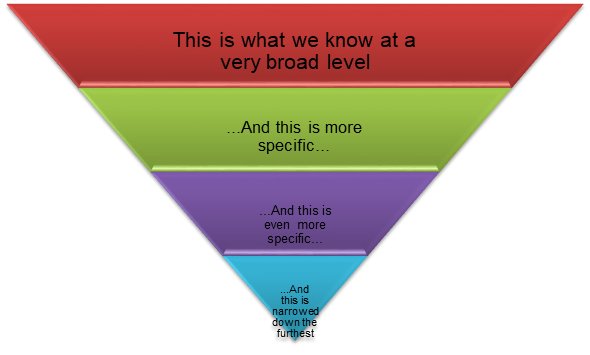

The ‘pyramid’ approach to structuring your literature review

Another common approach is the pyramid one, where you start with the broadest area of literature on your topic, and then narrow downwards to more specific knowledge leading on to your research question.

Pyramid approach to writing up a literature review

Summary

Ultimately, a literature review is not about showing that you are smart and know things, or that you can follow a pre-specified methodology. It’s about drawing on all your knowledge and skills to present your best understanding of the answers to your question(s), to date.

You are to become the master in this field. And your reader is looking to you to give them an informed, rigorous, and up to date understanding. Sometimes, the hardest bit of doing a literature review is feeling the confidence to be able to do that (see my blog on the Research mindset). But you can, providing you choose your scope and your methods wisely.

Further reading

There are several texts on how to write a literature review, relevant to the counselling and psychotherapy field. Torgerson’s Systematic reviews is a good general introduction. 7 steps to a comprehensive literature review has been recommended to me, and there is the popular Doing a literature review in health and social care. John McLeod’s classic Doing research in counselling and psychotherapy gives some excellent guidance on reading the literature (Chapter 2).

Acknowledgements

Photo by Jakirseu, CC BY-SA 4.0

Disclaimer

The information, materials, opinions, or other content (collectively Content) contained in this blog have been prepared for general information purposes. Whilst I’ve endeavoured to ensure the Content is current and accurate, the Content in this blog is not intended to constitute professional advice and should not be relied on or treated as a substitute for specific advice relevant to particular circumstances. That means that I am not responsible for, nor will be liable for any losses incurred as a result of anyone relying on the Content contained in this blog, on this website, or any external internet sites referenced in or linked in this blog.