The concept of non-directivity emerged in Carl Rogers’s work in the 1930s and 1940s as an alternative to the therapist-led counselling of his day. There, the clinician defined the interview situation, asked questions, diagnosed, and proposed particular activities (if you’re interested in its origins, do get hold of a copy of Rogers’s early work, Counseling and Psychotherapy). Rogers’s ‘non-directive’ approach was a radical innovation, which aimed to put the client’s own goals and understandings at the very centre of the therapeutic work. Underlying this was a humanistic ethic that placed ‘a high value on the right of every individual to be psychologically independent and to maintain his [or her] psychological integrity’ (p. 127).

Looked at today, it seems to me that there is still enormous value in emphasising the client’s right to direct their own therapy. Just as one example, for instance, when I’ve analysed interviews with young people in person-centred school counselling, it is clear that some really value not being told what to do by the counsellor. They say things like, ‘The counsellor asked me questions, but she didn’t push me. That felt calm and relaxed (and much better than the person I had before who was just talking all the time/getting me to do things).’ ‘Non-directivity’, then, can clearly be helpful for at least some clients some of the time; and, even without that, there would be an ethical argument for starting therapy with the client’s own directions. That’s why, perhaps, a ‘person-centred’ approach is becoming increasingly dominant in the health and social care fields. That doesn’t mean a strictly Rogerian practice, but one that aims to put the client right at the heart of the decision-making process. Health Education England, for instance, write:

Being person-centred is about focusing care on the needs of individual. Ensuring that people's preferences, needs and values guide clinical decisions, and providing care that is respectful of and responsive to them.

So, in that sense, Rogers’s basic principle of ‘non-directivity’ has been accepted as a starting point for the whole care field, and is, in many ways, incontrovertible. I think that’s great. I also think that it’s really important that, on counselling and psychotherapy training courses (pretty much of any orientation), trainees are taught the discipline of being able to recognise their own particular directions and agendas, and to try and de-prioritise these in favour of the client’s.

However, it’s worth noting the change in terminology — from ‘non-directivity’ to ‘person-centred’ — and to a great extent that is evident in Rogers’s work too. In his later books he uses the term ‘non-directive’ a lot less: indeed, it’s not even there in the index of his 1961 classic: On becoming a person. Personally, I think that’s a good thing: for me, while the ethos of non-directivity is incredibly important, the term is problematic for a few inter-related reasons.

First, from an intersubjective standpoint, it doesn’t make much sense to talk about being ‘non-directive’. Intersubjectivity is the philosophy that human beings only exist in relation to each other; and, if that’s the case, then simply being in the room with another person will have some influence on them. Here, then, we can never not direct another, and that’s what comes through in the research. For instance, some of the young people whose interviews I’ve looked at find it really awkward when the counsellor doesn’t say much, and particularly when there’s silence. I’m sure the counsellors, here, are trying to be non-directive and not leading but, actually, it has a very powerful effect on the client. So there’s no ‘neutral’ when it comes to counselling, no pure reflection; and it’s probably important that therapist know that so that they can think about the impact that their behaviours are having, whatever they do. If they try to direct, it will influence the client in certain ways; but if they try not to direct, it will also influence the client in certain ways. The term ‘non-directive’ seems to imply that we can act without influence, and that, I think, occludes rather than clarifies what happens in the counselling room.

Second, I think that the term ‘non-directivity’ can lead to a particularly passive understanding of person-centred practices — especially for trainees who are new to the field. What we see with young people is that, although most do really love their counselling, there is a significant minority (maybe 15% or so) who experience their person-centred counsellor as too passive: too quiet, too purely reflective — not offering enough input or advice. Again and again, too, when I ask my adult clients about their previous therapies I hear things like, ‘She was really nice, but she just didn’t do anything, and I am not sure I got much out of it.’ So I think that person-centred therapists need to be wary about ‘sitting back’ too much — at least with some clients. Person-centred therapy, per se, can be incredibly active and dynamic — the therapist fully present and immediate in the room. But I think the term ‘non-directive’, all too easily, points away from that: it infers not-doing, not-acting, not-taking initiative. ‘Person-centred’ or ‘client-centred’ or ‘client-oriented’ seem much better terms to me: that emphasise that the therapy is based around the client but don’t position the therapist as, inherently, non-active in that.

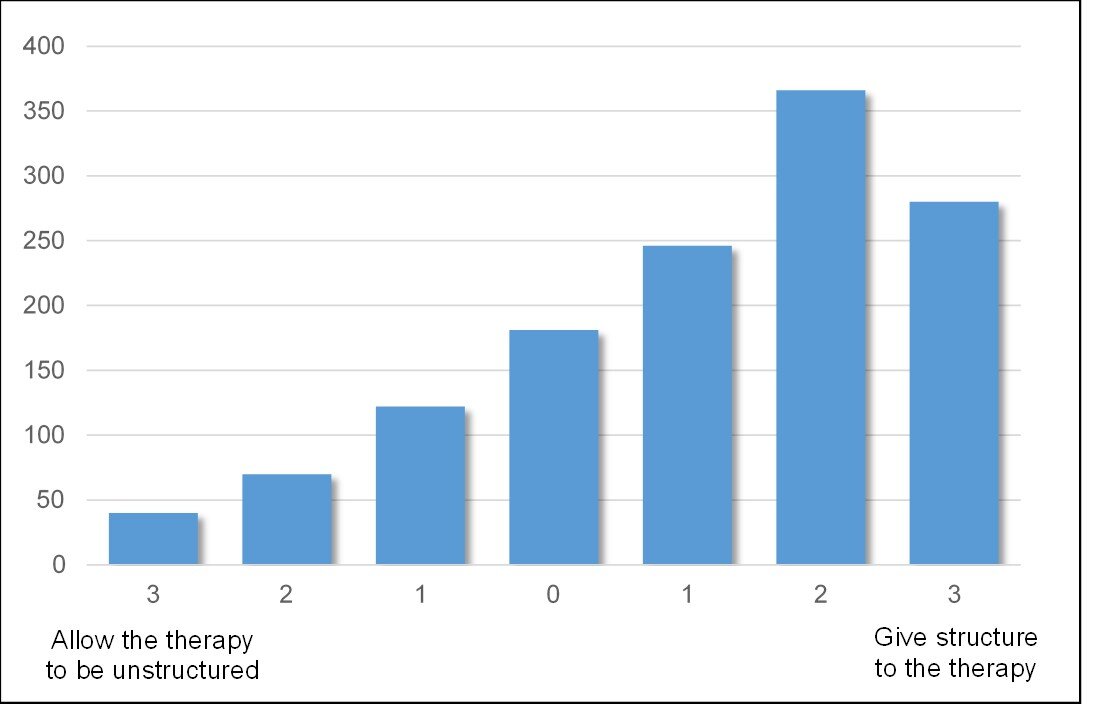

Third, the concept of ‘non-directivity’ throws up a paradox: because what does it mean to be non-directive with a client who wants direction? And it’s certainly the case that that’s what some clients wants. Take the graph below, for instance, from some research we recently conducted on individuals’ preferences for therapy. Respondents were asked to say what they would want a therapist to do, from a scale of 3 (Allow the therapy to be unstructured) to 3 in the other direction (Give structure to the therapy). Here, around 65% of respondents were saying that they wanted a structured, therapist-led approach; compared with around 15% wanting an unstructured approach: and that was similar on all our other therapist directiveness dimensions.

So, if a client is scoring a ‘3’ for wanting structure in their therapy, what is the ‘non-directive’ thing to do? You could say, ‘Well they’re asking for structure, but really they need to learn to live without structure and find their own direction,’ but that seems to be putting the therapist’s perspective before the client’s — hardly non-directive! So a more non-directive approach, it seems to me, is to try and accommodate the client’s preference and provide some structure (if we can and if we genuinely think it might be helpful for the client) — and this is what we’ve tended to advocate in pluralistic therapy (see here). But then the term ‘non-directive’ doesn’t seem to particularly fit any more. Not unless we say that being ‘non-directive’ can include such therapist-led activities as providing structure, activities, and guidance — but that’s really not what the term would seem to suggest. So, again, I think terms like ‘person-centred’ or ‘client-oriented’ are much better ways of expressing that desire to actively align ourselves with the client’s own directions: to put their wants and preferences right at the heart of the therapeutic work.

Finally, I think the term ‘non-directivity’ implies that, as therapists, we can act without directions when, actually, directions are inherent to all our actions. That’s something I’ve particularly focused on in my most recent book, which argues that ‘directionality’ is an essential quality of human being: that forward-moving, agentic thrust of being that can exist unconsciously as well as consciously. This means that, as therapists, we are never not trying to do something. We might want to be conveying empathy to our clients, or understanding them, or facilitating their own self-empowerment; but these are all directions in themselves, and recognising what these directions are is probably more important — in terms of our own self-awareness — than assuming (or hoping) that we’re acting without direction. This links to the earlier point that we’re always going to influence another, whether we like it or not.

I guess, in conclusion, what I am saying is that, although the thinking and ethics behind the term ‘non-directivity’ are of critical importance, the term, itself, is not always a helpful one. It’s good in reminding therapists to recognise, and de-prioritise, their own agenda; but it can imply an individualistic understanding of human being, and it points towards an interpretation of person-centred practice which is too passive and too non-engaged for some clients. In fact, I would say that it’s maybe time to drop the term from our training and literature, and instead to focus on being ‘client-’ or ‘person-’ centred, and what that really means. Or maybe we think about person-centred therapy as an approach which, fundamentally, strives to align itself with the direction of the client and to facilitate that. So not ‘non-directive’ but ‘client direction-centred’. Person-centred therapy, ultimately, isn’t about lack. It’s about dynamism, responsiveness, presence. And I think there are better terms that convey that deep engagement with clients. We’re not non-something. We are something. And emphasising what we are is, I think, a more constructive and positive way forward for the person-centred approach.

[Image by Agnieszka Zapart: see https://www.facebook.com/PsychoterapiaGestaltAgnieszkaZapart/ for her wonderful illustrations]