From a person-centred standpoint, advice is very much a no-no. Indeed, it’s virtually a taboo in the person-centred field: the first thing you learn when you learn about practising non-directively. That’s not surprising given where Carl Rogers, its founder, came from. He wanted to counteract the expert-led tendency of the therapies of his day (the 1930s and 1940s), which involved the therapist telling the client how to solve their problems. It assumed that the clinician knew: about the client’s life, about the best way forward for them, about how they should live their life. Rogers reacted, and many of us still baulk today for these same reasons: who gives the clinician the right to think they know better than the client about the client’s own life?

Given that advice-giving is so intrinsic to how many us learn to ‘help’ others, it seems essential to me that counselling trainings should start with learning how not to give advice: to bracket that need and to learn to just be with clients so that they can develop their own skills in problem solving. If we just ‘leap in’ all the time, we may really get in the way of that. It’s also important for trainees to recognise that, in many cases, giving advice can be more about the ‘kick’ we get from being smart and showing that we know things, rather than coming from a genuine desire to help the other. Amongst the many different forms of therapy responses, research shows that advice is rated as one of the least helpful.

I know that for myself, as a client. If a therapist tries to give me advice, I nearly always feel patronised, directed, belittled. It makes me feel like, ‘Why the hell do you think you can tell me what to do, after years of me trying to sort it out for myself.’

But sometimes, actually, I have found it helpful. One of the most helpful things a therapist ever said to me, and actually probably one of the least humanistic, was this: ‘Why don’t you think of what a “normal” person would do in those circumstances and try and do that.’ On pretty much every index that’s a ghastly intervention, but actually it was incredibly helpful for me and something that supported me through a lot. And I think the danger in dismissing all forms of advice is that we may actually then not see when it can be helpful—as us pluralists say—for different clients at different points in time. So there is another side to this.

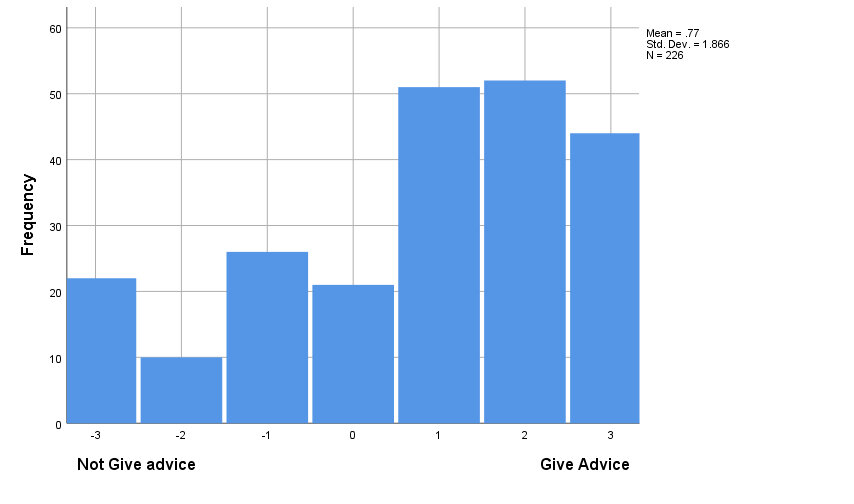

For a start, we’ve found in our research with young people in school counselling that, again and again, they say that they value the advice that they get from the counsellor (and you can see a great review of the evidence here). And this is kids in person-centred counselling. Of course, I’m sure sometimes what they are calling advice is actually the therapist reflecting back to them what they, themselves, worked out; but the point is that they see it as advice, and they love it. Along similar lines, we’ve found in our surveys on therapy preferences that about two-thirds of individuals want a therapist to give them advice, against about a quarter who don’t (see chart below). You could say, ‘Well, that’s because they don’t really know what therapy is or what’s really going to help them’; but then, paradoxically, that’s the essence of a therapist-expertise stance: saying what clients really need even if clients are saying something different.

Participants preference for advice vs not advice from a therapist, using the C-NIP form

Part of the issue, I think, is that the word ‘advice’ tends to be used in a very generic and non-specific sense, when actually it can cover a whole spectrum of different responses to clients. It’s one thing to say to a client, ‘You really ought to be kinder to your mum and, if you aren’t, you should feel ashamed of yourself’ (which, of course, no therapist would ever say); and quite another to say something like, ‘I wonder if you have ever thought about telling your mum how you’re feeling.’ So while the first kind of pressuring, very rigid advice might be unhelpful for nearly all clients; something much softer and more tentative may be of greater therapeutic value, and not have the effect of pressuring the client in any one way. So we need to nuance what we mean by ‘advice’.

Closely related to that is the fact that we are always influencing our clients—just by being there in the room with them—so there isn’t really any such hard division between ‘influence’ vs. ‘non-influence’. Rather, there’s different degrees of influence and some of the most powerful ways may be the most implicit. For instance, if we smile when a client tells us about their feelings we are implicitly conveying to them that they are doing something of value. Or, if we encourage them to think about their genuine needs, we are conveying that it’s good to be authentic. That maybe isn’t explicit advice but it is a valuing of one particular way of being, and can have, effectively, pretty much the same impact. Indeed, you could argue that, by being implicit, it’s actually more coercive—perhaps giving direct advice is more congruent and transparent.

There’s also good reasons why clients might value advice. Sometimes, as I’ve argued in my latest book, we’re just don’t know the things we need to do to get to where we want to be. If my car breaks down, I need someone to tell me how to fix it. I don’t have some inner organismic sense of what I need to do. And, similarly, clients may need some guidance on how to make friends, or overcome anxieties, or give up alcohol. That’s not such a terrible thing to acknowledge, is it? The positive effects of psycho-educational approaches like social skills trainings show that clients can really gain a lot from such direct education.

Conclusion

I think there’s some very good reasons why therapists should be trained out of automatically giving advice; and it’s certainly not a response mode we should use more than sparingly—unless a client has specifically signed up for a psychoeducational approach. Helping people work things out for themselves is, I’m sure, generally a more sustainable form of learning. It’s also important that, if we’re giving advice, we’re skilled and knowledgeable about what we are saying: none of us want to be telling clients to do things that just aren’t helpful. So just to be really clear, I’m not saying in any way that we should just break with our training and start advising our clients, willy-nilly, on how to live their lives, what to do, what they should wear, etc. But I am saying that, in the person-centred and humanistic therapies, I think we have tended to get a bit ‘phobic’ about advice; and turned something that was a counteraction to some over-directive practices into a rigid ‘law’ about what we can and cannot do. From a pluralistic standpoint, and based on the evidence, advice can be helpful for some clients some of the time. And perhaps it would be better to be working out when it might be helpful, and what are the best ways of giving it at those times. For instance, I’m sure that tentative ways of advising, rather than impositional ones, are of greatest value to most clients. And asking clients whether they’d like advice or not is also, probably, a helpful practice so that clients don’t feel imposed upon. There’s also the question of what kind of advice is most beneficial? For instance, from our research with young people, we’re finding that it tends to be in two areas—social skills and coping behaviours—and developing knowledges in such areas may be very helpful in terms of optimising the value of advice-type responses.

Perhaps the question we always need to ask, as Teresa Cleary notes in her comments below, is whether our responses is in the best interests of the client, or whether it’s to meet some personal need or agenda. The problem with giving advice is that it is, indeed, often more the latter than the former; but not giving advice can also be so—if, for instance, it’s about conforming to some inner set of ‘shoulds’ about how counsellors behave. So there’s no easy answers. It’s complex. And while having some basic rule about ‘not giving advice’ is a great starting point in training, like all skills and competencies, it is something that can get nuanced and developed over time.