The following blog is for Master’s or doctoral level students writing research dissertations in the psychological therapies fields. The pointers are only recommendations—different trainers, supervisors, and examiners may see things very differently.

Many thanks to Jasmine Childs-Fegredo, Mark Donati, and Edith Steffen for comments and suggestions.

***

For doctoral students, the viva is the endpoint of your academic journey, and can be the most dreaded part. So what is it, and what should you do to make it go as well as possible?

The Set Up

Typically, you’ll have two examiners: an ‘internal’ (someone based at your university), and an ‘external’ (someone based at another university). The external usually carries more weight, and may have more influence on the final decision. You may also have a ‘Chair’ (normally someone based at your university as well), but their role will just be to manage the viva examination. They don’t have a role in assessing you.

Often, you can choose whether or not to have your supervisors present at the viva, though they won’t be able to say anything. This can feel like moral support, and they can take notes on what might need to be revised. However, you may also feel more pressure having additional people in the room.

Typically, a viva lasts for about 90-120 minutes, though that can vary a lot. If longer, you’ll normally get a short break.

What viva examiners often do is to go through your thesis chapter by chapter, asking questions and discussing with you aspects of your work along the way. Sometimes your examiners will take it turns to ask questions, or the external may take more of a lead. However, this can depend on the examiners’ areas of expertise. For example, if your external knows more about your methods, and your internal more about your content area, they may divide the questions up in that way.

Prior to the viva, both of your examiners will have read through your thesis, and written an independent report of what they make of it, and approximately what outcome they think you should be awarded. In the vast majority of cases, this will be either ‘minor amendments’ (for instance, adding more on reflexivity, discussing the limitations in more depth) or ‘major amendments’ (for instance, restructuring the literature review, revising the analysis). In a small number of cases, they may also feel that you need to collect more data—a very major amendment. It’s also possible that they’ll feel the thesis should fail but, thankfully, that’s very rare, and something that your supervisors would normally alert you to before you submit. Equally rare is that the examiners will just pass your thesis without wanting to see any changes at all, so it may be best to go into the viva assuming that the examiners will ask you to make revisions to some degree—even if it’s just correcting typos. Before they meet you, your examiners will also have met with each other and shared their views on your thesis, coming up with a list of questions to structure the viva by.

Your examiners may start by telling you their overall assessment of your thesis, or they may not. If this doesn’t happen, don’t read anything into it—some examiners just prefer not to do so.

After they’ve talked your thesis through with you, the examiners will ask you to leave the room (for 30 minutes or so), and then they’ll discuss with each other what they think the outcome should be and what changes they think you should make. Then they’ll invite you back in and share the result with you. If, as normal, they’re asking for some amendments, they’ll go through them with you but you won’t need to write them down, as you’ll be sent the feedback in writing soon after the viva.

What’s it For?

As an external examiner, what I’m wanting from the viva is three things. First, I want to make sure that the student has really written their thesis, and not got someone else in to do it for them. So that means I’m looking to see that they can talk about their work in a fairly fluent and knowledgeable way. Second, although I’ll come into the viva with an outcome in mind and some idea of the kinds of amendments that I might want to see, I’m also open to revising that, depending on how the candidate talks about their work. For instance, I might feel that they should have conduct a systematic literature review rather than a narrative one, but if they present a convincing argument for why they did the latter, then I may be happy to let that go. Third, I might want to convey—and explain—to the student why I think they should make certain changes to their thesis, and what those changes are.

Remember that your examiners, like your supervisors, will almost certainly want to see you get through. No one wants to fail anyone—we all know how much work a thesis takes. But we also will want to make sure things are fair: if it feels like you haven’t got your head around certain things, or done the work that you’ve needed to do, then it wouldn’t feel right to pass you alongside others. And we’re also aware that your thesis will be lodged publicly, for all to access and read. So we want to see it in the best shape possible: something you can be proud of and that reflects the best of your abilities.

How to Prepare

Before the viva, have a really good few read throughs of your thesis so that you know it well. You may have completed it several months before the viva, so it’s important to re-familiarise yourself with it—particularly the more tricky or complex parts.

Practice vivas are essential. Your supervisor(s) will often be willing to do this with you. If not, or as well as, do practice vivas with your peers or friends. Get them to ask you questions about your thesis—particularly the more difficult bits (like epistemology, or your choice of methods, or any statistical tests) so you can get practised at talking these elements through. Talk to your friends, your family, your cat about your thesis (as much as they can bear it) so that you’re really familiar with what you did and why.

What to Take to the Viva?

One of my personal bugbears, as an examiner, is when students come to a viva without a copy of their own thesis, and then have to borrow mine to answer questions. So make sure you bring yours along, with sections clearly marked so you can find your way around it when asked about different parts. It’s fine also to bring a notepad so you can write down questions.

Nerves

It can be really scary doing a viva, and your examiners should be well aware of that and sensitive to it—bear in mind that they will have gone through one of their own. So if you get really nervous at the start or during the viva, it’s normally fine to ask for just a bit of time to compose yourself—there’s no rush. You may even want to let the Chair or examiners know at the start, if you think that will help.

What Will They Ask Me?

Mostly, the questions that your examiners will ask will be specific to your particular thesis. As indicated above, typically, they’ll go through it chapter by chapter, and ask you to explain, or elaborate on, specific aspects of your work. The questions will often be on the areas that they feel might need further work. However, if they feel that really not much needs to be changed, they may just be asking about particular areas of interest to discuss them with you. After they’ve asked you about a particular area of issue, they may follow this up with further questions or prompts. Questions may be fairly general (for instance, ‘Can you explain your choice of analytical method?’) or very specific (for instance, ‘On page 125, you indicate that the p-value was .004, but on page 123 you write that the regression analysis wasn’t significant, can you explain that please’). There’s also some standard questions that examiners may ask, for instance:

Why did you choose to do this study?

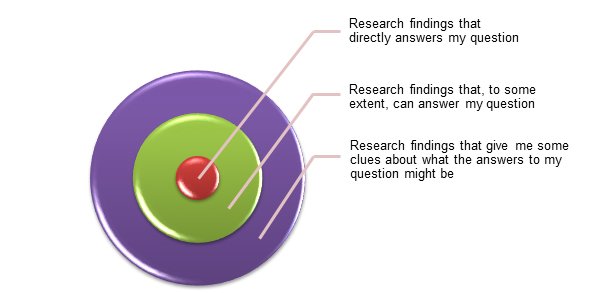

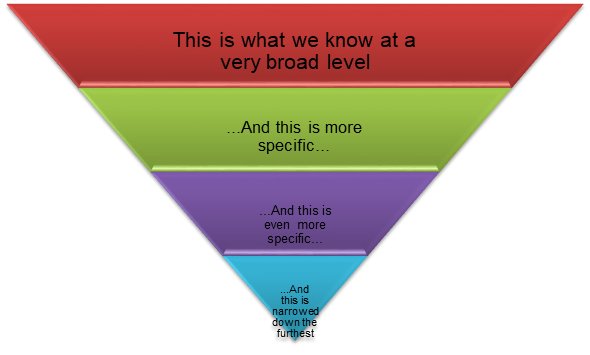

How did you go about choosing what literature to look at?

What was the underlying epistemology for your research?

What was the rationale for your sample?

Why did you choose this particular method? Why not xxx method?

What are the implications for counselling/psychotherapy/counselling psychology practice of your thesis?

What does your research add to the field?

What are the limitations of your study?

What was the impact of your personal perspective on the study? Biases?

What did you personally learn from the study?

Elaborate, Elaborate, Elaborate

In terms of the actual viva, the main bit of advice I would give candidates is to make sure you really elaborate on your answers. Of course, you want to stay on track with the particular question you’ve been asked, but don’t be too short or pithy in how you respond. For a typical viva, the examiners may have prepared, say, 10 questions or so, so you need to talk on each area for, perhaps, 10 minutes; and you don’t want a situation where your examiners are constantly having to pump you for answers. This is your chance to show your depth and breadth of thinking so, for instance, reflect with the examiners on why you made the choices you did, show how you weighed up different possibilities, talk about the details of what you considered and what you found. Ultimately, what your examiners want to see is that you can think deeply and richly and complexly about things—rather than that you have reached any single definitive conclusions. So it’s less about getting it ‘right’, and more about showing all the thinking that has been going on.

Don’t be Defensive

The other main thing I would say is not to be too defensive when you respond to the examiners’ questions and prompts. As indicated above, they’ll have a view on what they may want you to revise in your thesis, and while you may be able to change their minds to some extent, you don’t want to come across as too rigid or stubborn in your thinking. If, when they point something out to you, you think, ‘Actually, they’re probably right,’ that should be fine to say, and better than trying to defend something that you can clearly see is in need of adjustment. Of course, if you think you’re right, do say it and say why, but you don’t have to defend to the bitter end every element of your work. Better to show, like all of us, that you can sometimes get things wrong and that you’re open to learning and improving.

Be the Expert You Are

As Mark Donati, Director on our Doctorate in Counselling Psychology at the University of Roehampton suggests, don’t be afraid to express your opinion and say what you really think. Of course, it’s best if this is based on the available evidence; but sometimes the evidence just isn’t available, and then the examiners may be really interested in your ‘best guess’ of what’s going on. Remember that you are the expert in the area now. That’s right, you are. And the examiners may be really excited to hear from you what the view is from the leading edge of the field.

Don’t Shame your Examiners

That might sound strange to say, but bear in mind that your examiners are also in a social situation, and may be experiencing their own pressures to ‘perform’. Dr X, for instance, has come down from University Y, and it’s the first time they’ve met your internal examiner Professor Z, whose work they’ve always admired, as well as Chair W, who they don’t know very well but who seems an important figure. So Dr X wants to show that they’ve got a good understanding of your work, with some intelligent questions to ask, and some good insights about the field. What that means is, if you want to keep your examiners ‘on side’, treat them with respect and show an interest in what they’re saying and the questions they asked. You really don’t want to respond to Dr X in a way that may make them feel foolish in front of Professor Z, or like they have to defend themselves. What this also means is that some of what goes on in the room may not be about you, but also about the dynamics between the rest of them.

Enjoy

It’s easier said than done, but if you can enjoy your viva (and many students do end up doing so) then that’s great. Think of it this way: you’ve got a captive audience for two hours who you can talk to about all the work you’ve been doing for the last few years. And now you’re the expert, so make the most of it: tell them about what you’ve been really thinking, and about some of the complex challenges doing the thesis, and about all your ideas about where the research should go for the future. It’s your chance to shine, and if you can really connect with your energy and enthusiasm for your work, your examiners are sure to appreciate that—and so might you.