This article—published in 2009 as Cooper, M. (2009). Welcoming the Other: Actualising the humanistic ethic at the core of counselling psychology practice. Counselling Psychology Review, 24(3&4), 119-129—strives to articulate the ethical principles at the heart of counselling psychology. A pdf of this paper is available here.

***

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the question of how counselling psychology might move forward into the future. It argues that, for many counselling psychologists, the defining feature of our profession lies in a humanistic value-base; and that, to move forward, we need to look at how that could be more fully actualised. The paper argues that this value-base is most succinctly expressed in Levinas’s concept of ‘welcoming the Other,’ and it proposes five ways in which this ethic might be taken forward: developing our capacity to see beyond diagnoses, enhancing our responsiveness, focusing more fully on our client’s intelligibility, taking a lead in giving psychology away, and developing our evidence base. The paper concludes by suggesting that the key issue is not the survival of counselling psychology as a profession; but the survival, development and proliferation of this value-base.

KEYWORDS

Counselling psychology, humanism, humanistic psychology, ethics, social responsibility

***

There is no doubt that counselling psychology – and the psychological therapies more generally – are at a time of great turbulence and change. Regulation by the Health Professions council has arrived; the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Programme is rolling out across the UK; and Skills for Health competences and National Occupational Standards have been developed for the principal therapeutic modalities. While counselling psychology in the UK, then, has considered its identity and future for many years (e.g., Spinelli, 2001); it is no surprise that the last few years has seen a particularly intensive period of self-reflection (see, in particular, the special edition of Counselling Psychology Review (24: 1, March 2009): Counselling Psychology – The Next 10 Years).

For some in the field, the expectation is that counselling psychology will slowly become amalgamated with, or subsumed by, clinical psychology (Anonymous, 2009; Giddings, 2009; Turpin, 2009). Peter Kinderman, Professor of Clinical Psychology and chair of the BPS’s Standing Committee for Psychologists in Health and Social Care writes: ‘I think that any distinctions between counselling and clinical psychology are becoming nugatory [of little value]…. So… in ten years time… I suspect there will no longer be many people registered with the HPC as “counselling psychologists”’ (2009, p. 20).

The aim of this paper is to examine how counselling psychology might move forward into the future. To do so, the paper beings with the question, ‘What is the core of counselling psychology?’ and argues, as others have done (e.g., Kanellakis, 2009), that it lies in a set of humanistic values and ethics. It then goes on to try and articulate the essence of these values, locating it in Levinas’s (1969) concept of ‘welcoming the Other.’ The paper then outlines five ways in which counselling psychology might more fully actualise this essence: developing our capacity to see beyond diagnoses, enhancing our responsiveness, focusing more fully on the intelligibility of our clients, taking a lead in giving psychology away, and developing our evidence base. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implications of such developments for the identity and future of counselling psychology.

THE ESSENTIAL VALUES OF COUNSELLING PSYCHOLOGY

For many counselling psychologists, the essence of our profession, what makes it distinct from other psychological professions, is that it is embedded in a particular set of values and ethics (e.g., Walsh & Frankland, 2009; Woolfe, 1996). Ralph Goldstein (2009, p. 36), for instance, writes: ‘Counselling psychology is unique in that its competencies are founded upon a philosophically-orientated and explicit statement of values.’ More than that, though, it might be argued that counselling psychology is not only grounded in a set of values – as all professions might be held to be (Koehn, 1994) – but that it is, in its essence, the application of those values. In other words, ‘our respect for our client’s autonomy, our trustworthiness, our commitment to maintaining confidentiality are not just corollaries of our work – they are the essence of what we do’ (Cooper, 2009): counselling psychology is ‘ethics-in-action.’

What are these essential values? Across a range of core counselling psychology texts (British Psychological Society Qualifications Office, 2008; Gillon, 2007; Orlans & Van Scoyoc, 2008; Woolfe, 1996), six key principles can be identified:

A prioritisation of the client’s subjective, and intersubjective, experiencing (versus a prioritisation of the therapist’s observations, or ‘objective’ measures).

A focus on facilitating growth and the actualisation of potential (versus a focus on treating pathology).

An orientation towards empowering clients (versus viewing empowerment as an adjunct to an absence of mental illness).

A commitment to a democratic, non-hierarchical client—therapist relationship (versus a stance of therapist-as-expert).

An appreciation of the client as a unique being (versus viewing the client as an instance of universal laws).

An understanding of the client as a socially- and relationally-embedded being, including an awareness that the client may be experiencing discrimination and prejudice (versus a wholly intrapsychic focus).

Within the literature, these principles are often associated with humanistic psychology, such that counselling psychology is frequently defined as having a ‘humanistic value-base’ (Joseph, 2008; Orlans & Van Scoyoc, 2008; Walsh & Frankland, 2009; Woolfe, 1996). This is evident when one considers the core values of humanistic psychology, which overlap, to a great extent, those of the counselling psychology field:

Human beings, as human, supersede the sum of their parts. They cannot be reduced to components.

Human beings have their existence in a uniquely human context, as well as in a cosmic ecology.

Human beings are aware and aware of being aware – i.e., they are conscious. Human consciousness always includes an awareness of oneself in the context of other people.

Human beings have some choice and, with that, responsibility.

Human beings are intentional, aim at goals, are aware that they cause future events, and seek meaning, value, and creativity. (Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 2009)

But what is the essence of these counselling/humanistic psychology values? What links them, underpins them, is the rationale for why they exist in the way that they do? Cooper (2007, p. 11) argues that the core ethical commitment underlying humanistic practices is one of ‘humanisation’: ‘a commitment to conceptualizing, and engaging with people in a deeply valuing and respectful way.’ That is, practitioners from a humanistic value-base strive to engage with their clients, first and foremost, as agentic human subjectivities who can not be reduced to, or treated as, objects of natural scientific inquiry.

This humanizing ethic is eloquently articulated in Buber’s (1958) concept of the ‘I-Thou’ attitude. From this stance, we behold, accept and confirm the Other as a unique, un-classifiable and un-analysable totality: a freely-choosing flux of human experiencing. Buber contrasts this with the ‘I-It’ attitude, in which the Other is experienced as a thing-like, determined object: an entity that can be systematised, analysed and broken down into universal parts.

LEVINAS: WELCOMING THE OTHER

Perhaps a more contemporary, simpler and, in some ways, more fundamental expression of this underlying humanistic ethic, however, lies in Levinas’s (1969) notion of ‘welcoming the Other.’ Levinas is not normally associated with humanism and, indeed, argued that it should be ‘denounced,’ but only on the grounds that it is not ‘sufficiently human’ (Davis, 1996, p. 84). For Levinas, the humanism of man as an autonomous, self-creating source needed to be replaced with a ‘humanism of the Other’ (Levinas, 2003), in which the ‘Thou’ – ‘the stranger, the widow, the orphan, to whom I am obligated’ (Levinas, 1969, p. 215) – is given precedence over the I.

But what does Levinas (1969) mean by welcoming the Other? Here, he is referring to something much more than a friendly hospitality. For at the heart of Levinas’s (1969) ‘ethical metaphysics’ is an emphasis on honouring the Other, in all their otherness. The Other, writes Levinas, is ‘infinitely transcendent,’ ‘infinitely foreign,’ ‘infinitely distant,’ ‘irreducibly strange.’ He or she always overflows and transcends my idea of him or her, is impossible to reconcile to the Same, is always more than – and outstrips – the finite form that I may afford him or her. So, for Levinas, a welcoming of the Other means a deeply challenging willingness to let the Other be in all their Otherness. It is a ‘non-allergic reaction with alterity’ (Levinas, 1969, p. 47), in which the self does not attempt to neutralise the Other and reduce it down to a familiar theme or object. Rather, it is a recognition and acknowledgement of the Other in their fundamental unknowability: a privileging of the unique, human ‘face’ of the Other over ‘psychagogic rhetoric’ (i.e., psychological theories, assumptions and dogma). It is also, as Levinas (2003) writes, an acknowledgement of the ‘inexpressible irreversibility’ of the Other: that the essence of the Other is not something that can be intervened in or changed.

The contention in this paper, then, is that this stance of welcoming the Other is an articulation of the essential ethic and politic that, for many of us, underlies counselling psychology. It is through this desire to respect and validate the Other in the totality of their being that we start with their unique subjective experiencing; relate to them as beings who have the capacity to grow; and understand them in terms of the social, economic and cultural limitations that they might face.

Moreover, as suggested earlier, this ethic of welcoming the Other is not just a corollary to our therapeutic practice; it is its very essence. Through a welcoming of our clients, the hope is that they will come to feel more welcoming of themselves and their own ‘self-otherness’ (Cooper & Hermans, 2007) and to feel more integrated into the human community. There may also be a hope that they will come to develop a more welcoming attitude to Others and otherness in their own lives. As Cohen (2002, p. 48) writes, ‘The road from mental illness to mental health is…to regain one’s obligations, one’s responsibilities to and for the other.’ The gentleness of the word ‘welcoming,’ then, belies its capacity to profoundly challenge clients. It is a deep, radical welcoming, with the potential to evoke dramatic transformations in clients’ lives: to challenge shame, self-hatred, repression, isolation, blame and other forces of intra- and interpersonal dis-ease.

SEEING BEYOND DIAGNOSES

So how would counselling psychology develop if we attempted to actualise this ethical commitment more fully? First, it might lead us to find ways of holding on to, and deepening, our understanding of clients as ‘trans-diagnostic’ beings (i.e., beyond any particular label or category). This is not to suggest that diagnoses and tests cannot be helpful in the practice of counselling psychology. This issue has been extensively debated in the field (see, for instance, Sequeira & Van Scoyoc, 2001, and special edition on Counselling Psychology and Psychological Testing, Counselling Psychology Review, 19: 4, November 2004), and it is clear that diagnostic and testing procedures can be experienced by some clients as helpful, reassuring and empowering, particularly when used in a collaborative way (Fischer, 1970). But when the diagnosis is put before the ‘face’ of the client, when the client is seen as their diagnosis -- ‘the depressive,’ ‘the borderline patient’ – then there is a clear ‘thingification’ (Levinas, 2003) of the Other: an attempt to reduce their complex, unknowable Otherness to the familiar and the Same.

Somewhere in the realm of the psychological professions there needs to be practitioners who can welcome – and work with – the richness and vastness of clients beyond their diagnoses. To give an example: Daryn was a slight, 30-year-old man of Afro-Caribbean origin who came to therapy with me wanting to find out ‘Who he really was’ (see Cooper, 2008b for full case illustration). About seven years previously, Daryn had been hospitalized following a period of severe disorientation, and had spent six years moving in and out of psychiatric institutions, diagnosed with a variety of mental illnesses and treated with a range of anti-depressant and anti-psychotic medications. Daryn described this time as ‘horrific’: like a nightmare that he still could not believe had really happened. He said that he had found the psychiatric system dehumanizing, impersonal and painful, and talked about a number of instances in which he had felt deeply humiliated by the psychiatric staff. As we started to work together, what became quickly apparent was that Daryn, more than anything else, just needed to be heard: about his experiences in hospital, about the factors that brought him to the point of breakdown, about his feelings of helplessness, about the thoughts and fantasies that ricocheted around his head and, increasingly, about his strengths and abilities. Daryn needed to come to know himself outside of medical and diagnostic contexts and, as he did so, so his confidence and sense of wellbeing improved.

For Daryn, the essence of what worked – what he described as ‘life saving’ – was a willingness to validate, and support, the Daryn-beyond-the-label. This was not just about putting any diagnoses temporarily to one side, it was about radically, transformatively encountering Daryn as a person, in all his uniqueness and potentiality. This would not have been possible had Dayrn been met, first and foremost, as a ‘schizophrenic in remission,’ as a ‘manic depressive,’ or as a representative of any other psychodiagnostic class.

Daryn, of course, is not representative of all clients; but his antipathy to diagnosis and labelling is not unique. There are many, perhaps a majority of, clients in clinical settings that want to be engaged with as distinct individuals, with a depth and complexity that far exceeds their diagnoses. Professionals are needed who can engage with people in this way, who can hold labels lightly and meet people, first and foremost, as people. Many, if not all, counselling psychologists already adopt such a stance, but it is a mode of relating that we can hold on to and, where possible, advance. Even if we are working within such diagnostic-based treatment programmes as IAPT, we can still work to ensure that our clients feel understood and embraced in the totality of who they are, and not just in the diagnosis around which their treatment is based. This is a distinctive contribution that counselling psychology can, and can continue to, bring to the psychological field.

ENHANCING OUR RESPONSIVENESS

At the heart of a welcoming attitude to the Other is a willingness to attune, and be responsive, to his or her unique needs and wants. If we welcomed a guest into our home with a drink, we would find out what he or she, specifically, wants – we would not offer every guest coffee, two sugars, no milk. A welcoming attitude also means being responsive to the changing needs or wants of the Other. Stiles and colleagues (Stiles, Honos-Webb, & Surko, 1998, p. 440) contrast a responsive stance with one of ‘ballistic action,’ where behaviour is ‘determined as its inception and carries through regardless of external events’ (think of throwing a ball which, once released, carries along its trajectory).

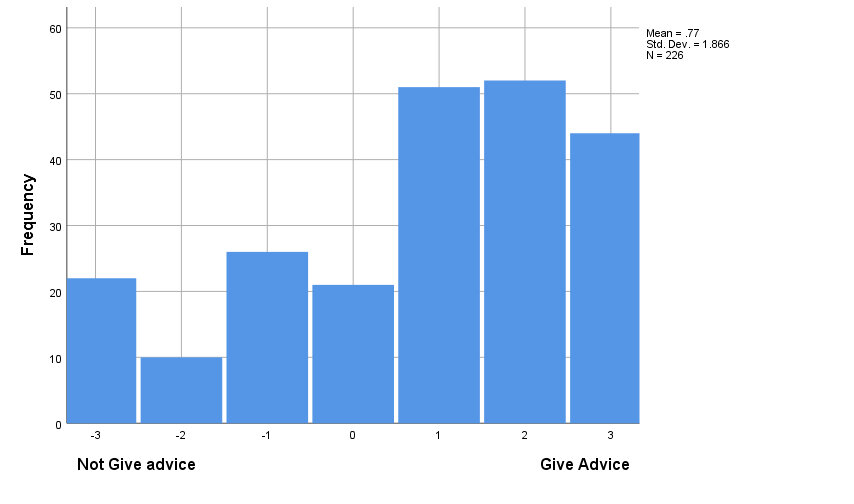

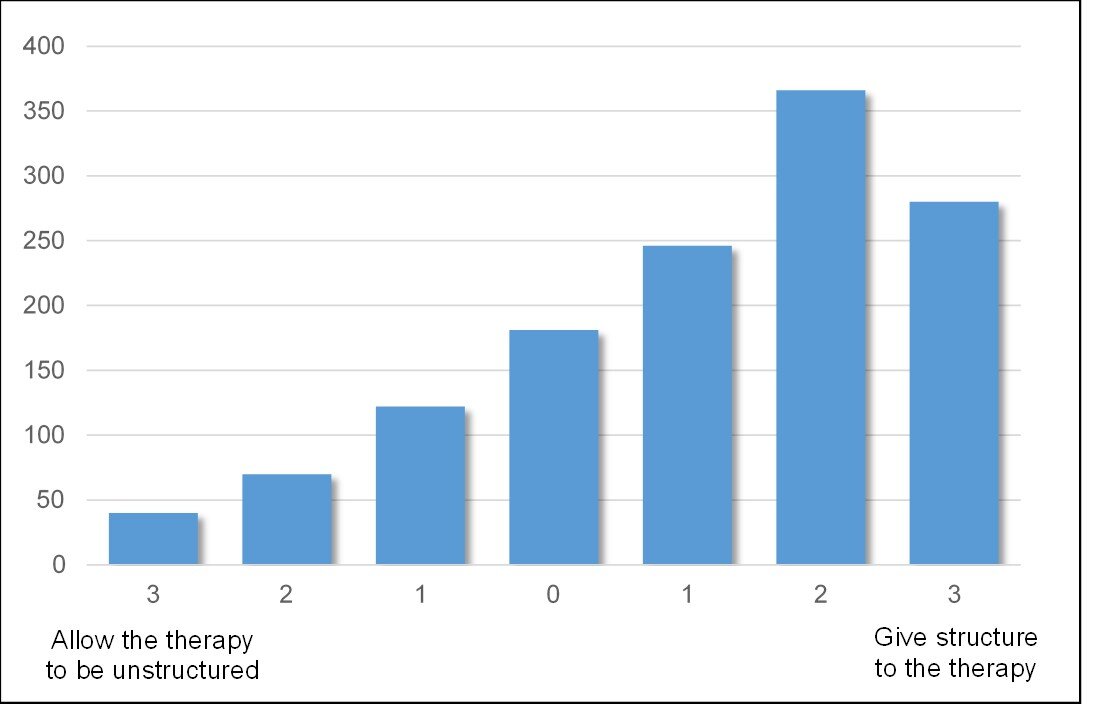

In this respect, a second way of deepening a stance of welcoming towards clients is by looking at ways in which we might be more fully responsive to their unique wants and needs. In the pluralistic framework for counselling and counselling psychology, for instance, being developed by Cooper and McLeod (2007), there is a particular emphasis on dialogue around the goals and tasks of therapy: talking with clients, from the very inception of the psychological work, about what it is that they want, and how they think that might be achieved. Researchers in this field have also been looking towards the development of a ‘Therapy Feedback Form,’ in which clients can indicate on a series of dimensions how they think therapy might be improved: for instance, ‘more structured – less structured,’ ‘more exploration of the past – more focus on the present.’ Such work is based on the assumption that, as therapists, we are often very poor at knowing what clients want from therapy or how they experience it (Cooper, 2008a), such that the best route towards understanding the clients’ wants and needs is generally through asking them.

Of course, clients are not always able to articulate what they want from therapy, but a discussion of their hopes, fears, preferences and understandings nearly always elicits some valuable anchors around which the work can be orientated. As an example, Marcel was a young man who was referred to me with social anxiety: in particular, fears of speaking in public. He had had a previous episode of counselling, and much of that work was focused around some experiences of abuse he had suffered as a boy. In our first two sessions, we also talked about this abuse, but in the third session, when I asked Marcel how he was finding the therapy, he said that he was really not sure whether he wanted to go into the abuse again: as far as he was concerned, it was pretty much resolved. ‘Do I really have to discuss it again?’ he asked.

In response, I said to Marcel, ‘I guess part of the question is how much is it related to the problems that you are experiencing at the moment,’ and we went on to explore the various factors that may have led him to experience his social anxiety: the abuse; perhaps some humiliation that he experienced at school; or maybe a cycle that he had got into of avoiding talking in public, such that those situations then felt more and more terrifying.

‘I’m just thinking about those: it could be a pattern of behaviour I’ve just got into…’ Marcel said. Over the next 10 sessions, the principal focus of the work then became this withdrawal and avoidance cycle. Marcel left therapy with a significantly reduced level of social anxiety.

In this work with Marcel, I did not start with a specific formulation of Marcel’s difficulties, or a plan for treating them. Rather, the focus of the work emerged through dialogue with Marcel about the psychological roots of his problems, and how he believed that they could be addressed most effectively.

In this case illustration with Marcel, what is also apparent is that a commitment to a humanistic ethic does not necessarily entail the implementation of a specifically humanistic form of therapeutic practice (such as client-centred or gestalt therapy). What is clear from the psychotherapy research is that some clients prefer a cognitive behavioural approach to a humanistic one (King et al., 2000); and that some clients (such as those who tend to externalise and who have low levels of resistance) do do better in the former approach as compared with the latter (and vice-versa, Cooper, 2008a). So to ‘impose’ a humanistic form of practice on every client – even if it is through implicitly conveying to them that ‘this is how therapy is done’ – could be considered profoundly ‘un-humanistic.’ In this respect, it may be useful to distinguish between humanism as an ethic underlying psychological practice, and as a specific family of therapeutic interventions (Cooper, 2007). It is this distinction that allows us to resolve the paradox that, while counselling psychology is a humanistic discipline, it does not have to just involve the practice of humanistic therapies (Gillon, 2007). As Stephen Joseph (2008) argues, it is quite possible to practice CBT from a person-centred philosophical base.

Through deepening our responsiveness to clients counselling psychologists could do much to enhance the distinctiveness of our profession. While counsellors and psychotherapists frequently ally to ‘uni-models’ (Milton et al., 2002) of therapy; clinical psychologists and implementers of high and low intensity CBT interventions are being increasingly encouraged in the direction of protocol adherence and manualisation (e.g., Pilling, 2008). No doubt, for many clients, this will be helpful; but there are also likely to be many clients who would prefer a more flexible, responsive mode of engagement. Here, then, is a virtually unique place in the landscape of psychological therapies that counselling psychologists could inhabit: practitioners with an expertise in responsiveness and the development of individually-tailored therapies.

ORIENTATING FURTHER TOWARDS CLIENT INTELLIGIBILITY

When we welcome guests to our home, we do not normally start by pointing out their flaws. Rather, we would start from the assumption that they are rational and able people, of no lesser competence than ourselves. Similarly, then, to welcome clients in to our therapeutic relationship means to start from the assumption that they are intelligent, meaning-seeking people who are striving, just as we are, to do their best in their given circumstances. A term that R. D. Laing (Laing & Esterson, 1964) uses to describe this is ‘intelligibility’: that there is a rationale and a meaning behind what people think, do and feel – however bizarre and irrational it may appear.

Such an orientation towards client intelligibility means that the focus of a welcoming psychology is less on clients’ deficits – their ‘mental illness,’ ‘pathology’ or areas of dysfunction – and more on what they are doing right, and how this can be built on.

But what would it mean for counselling psychologists to take a wellbeing orientation forward? On the one hand, it might be argued that this would take the profession further outside of the NHS, with its specific emphasis on treating psychopathological conditions. On the other hand, within both national health and wider policy circles, there are clear indications of a move towards more potentiality-based models of psychological functioning. In January 2005, for instance, the National Institute for Mental Health in England issued a Guiding Statement on ‘Recovery’ -- ‘a process of changing one’s orientation and behaviour from a negative focus on a troubling event, condition or circumstance to the positive restoration, rebuilding, reclaiming or taking control of one’s life’ – with the hope that this ‘will contribute to the development of recovery-oriented services nationwide’ (National Institute for Mental Health in England, 2005, p. 1);. Similarly, the much-publicised work of the UK Government’s Foresight Project on Mental Capacity and Wellbeing has placed the issue of ‘mental wellbeing’ at the forefront of government agendas. The executive summary of the project states: ‘Encouraging and enabling everyone to realise their potential throughout their lives with be crucial for our future prosperity and wellbeing’ (Foresight Mental Capital and Wellbeing Project, 2008, p. 9).

While it may be premature, then, for counselling psychologists to wholly abandon an understanding of psychological functioning in terms of ‘dis-ease’ and ‘pathology’; a deepened commitment to understanding clients as intelligible, wellbeing-orientated beings would make us ideally placed to take a lead in the development and implementation of recovery and wellbeing initiatives. Moreover, if, and when, a wellbeing agenda unfolds, there will be a need for psychologists with a special expertise in helping individuals – as well as organisations and communities – to achieve higher levels of fulfilment and life-satisfaction. Perhaps, in years to come, we shall see the emergence of ‘Wellbeing Psychologists’, whose specific role would be to help people attain greater levels of self-realisation, through the application of psychological theory and research.

GIVING PSYCHOLOGY AWAY

In his Presidential Address to the American Psychological Society in 1969, entitled ‘Psychology as a means of promoting human welfare,’ George Miller (1969, p. 1070) stated ‘[T]he secrets of our trade need not be reserved for highly trained specialists. Psychological facts should be passed out freely to all who need and can use them.’ He went on to say, ‘I can imagine nothing that we could do that would be more relevant to human welfare, and nothing that could pose a greater challenge to the next generation of psychologists, than to discover how best to give psychology away’ (1969, p. 1074). If counselling psychology, as a profession, strives to fully welcome our clients – supporting them to be more empowered in their lives – then finding ways of ‘gifting’ them our psychological knowledge and expertise, so that they are not dependent on us for it, should be at the heart of our psychological work.

How, as counselling psychologists, might we do this? Already, there is a burgeoning literature on self-help practices (e.g., den Boer, Wiersma, & van den Bosch, 2004), and this is something that counselling psychologists could be more actively engaged in, taking a lead in the development of ‘skilled clients’ (Nelson-Jones, 2002, 2003). An emphasis on giving psychology away could also lead counselling psychologists to become more involved at the level of community (Thatcher & Manktelow, 2007): using our knowledge and insight to help groups find ways towards improved wellbeing. For instance, we might be involved in projects to tackle prejudices and stigma in the mental health field (Galbraith & Galbraith, 2008), or supporting the development of school-based peer support and befriending programmes against bullying (Cowie, 2000).

For counselling psychologists, however, there is a particular challenge in giving away our psychological expertise. It is one thing to train clients in the self-administration of particular techniques or exercises; but what happens when one’s expertise lies in the capacity to form relationship? Is this not something that, by definition, requires our presence? Perhaps this is why humanistic and relational psychologists have been slower than those of a cognitive-behavioural orientation to find ways of giving psychology away. Yet, such a challenge is also an opportunity, and interpersonal psychotherapists have already shown how clients can be helped to develop more satisfying means of relating to others (e.g., Stuart & Robertson, 2003). Given that, as the research shows, psychological difficulties are strongly related to problems in interpersonal connections (Foresight Mental Capital and Wellbeing Project, 2008; Segrin, 2001), helping clients and communities to develop more satisfying and intimate means of relating could be a major contribution for counselling psychologists to make.

DEVELOPING THE EVIDENCE-BASE

While counselling psychologists tend to identify with the ‘scientist-practitioner’ model (Woolfe, 1996), a simple perusal of the number of research papers in Counselling Psychology Review suggests that the generation of empirical evidence – particularly of a quantitative, controlled nature – is not a high priority for many in the field. To a great extent, this is a consequence of the humanistic value-base of the profession, which questions the value of nomothetic data to an understanding of individual, unique human beings (Walsh, 2003); and which sees the essence of our clients – their complex, multifaceted totality – as lying far beyond the realms of the researchable (Rowan, 2001). Indeed, as Levinas (2003) argues, the essence of the otherness of the Other is that it is unknowable and ungraspable, and that an ethical stance requires us to let it be, rather than attempting to penetrate and expose it.

And yet, there is another way of thinking about empirical research – including studies of a highly quantitative, controlled, experimental nature – that is very consistent with a commitment to welcoming Otherness. While it is true, as argued above, that empirical research might lead us to impose nomothetic assumptions upon individual clients; the reality is that we will always come to our clients with certain assumptions about why they are the way they are and what is likely to help them. Research, then, also has the potential to challenge our pre-existing assumptions – presenting us with an ‘otherness’ that is unexpected, ‘infinitely distant,’ ‘irreducibly strange’ – and thus helping us to be more open-minded and responsive to the actual Other that we are encountering (Cooper, 2008a). Here is a personal example:

[A]s someone trained in existential psychotherapy (something I’ve defined as ‘similar to person-centred therapy… only more miserable’ (Cooper, 2003, p. 1)), my tendency in initial sessions had always been to warn clients of the limits of therapeutic effectiveness. That is not to suggest that I would start off assessment sessions by saying: ‘OK, so your life is meaningless, it has always been meaningless, you have no hope of change… and how can I help you?’ but I did tend to adopt a rather dour stance, emphasising to clients that therapy was not a magic pill and highlighting the challenges that it was likely to involve. Then I came across a research chapter by Snyder and colleagues (1999) which showed, fairly conclusively, that the more clients hoped and believed that their therapy would work the more helpful it tended to be. How did I react? Well, initially I discounted it; but once I’d had a chance to digest it and consider it in the light of some supervisory and client feedback, I came to the conclusion that, perhaps, beginning an episode of therapy with all the things that might not help was possibly not the best starting point for clients. So what do I do now? Well, I don’t tell clients everything is going to be fine the moment that they walk through the door; but I definitely spend less time taking them through all the limitations of the therapeutic enterprise; and if I think that therapy can help a client, I make sure that I tell them that. (Cooper, 2008a, p. 3)

Not only, however, do research findings present us with an otherness; but they present us with an otherness that, directly or indirectly, expresses the voice of the client. Of course, as psychologists, we may feel that we already have a good grasp of how clients feel about therapy but the evidence suggests that this is rarely the case. For example: therapists’ ratings of the quality of the therapeutic relationship tend to show only moderate agreement with clients’ ratings (e.g., Gurman, 1977; Tryon, Blackwell, & Hammel, 2007); and in just 30 to 40 per cent of instances do therapists agree with clients on what was most significant in therapy sessions (Timulak, 2008). Even the most mechanistic, experimentally controlled research, then, can help us stand back from our own beliefs about what happens in therapy and consider the process and outcomes from a more client-orientated perspective.

Developing the evidence base for counselling psychology is also essential if we are to take forward the agenda outlined in this paper. For each of the developments proposed above, there are numerous ways in which we need to develop our understanding. For instance:

Moving beyond diagnosis: How do we most fully acknowledge and validate the uniqueness of our clients? How can we draw on diagnoses and psychiatric knowledge without falling prey to it? What are ways of understanding clients if not by diagnostic nomenclature (for instance, in terms of their life-goals)?

Enhancing responsiveness: How can we be more responsive to clients? How can we find out more about what clients want and need in therapy?

Orientating towards client intelligibility: How do we help clients to draw on their own strengths and resources? How can we effectively measure actualisation of potential? How can we help people across the age ranges (and particularly older people, Foresight Mental Capital and Wellbeing Project, 2008) utilise their potential?

Giving psychology away: How can we help individuals and communities to develop relational skills?

Each of these are areas of empirical enquiry that counselling psychologists could be taking a lead in.

Also, in striving to actualise our ethical core, it would be very useful for counselling psychology to review, and perhaps redefine, its psychological knowledge base. Currently, for instance, much of the research and theory we draw on comes from the field of psychopathology – or personality, life-span development, and cognitive neuroscience (British Psychological Society Qualifications Office, 2008). But what of research, for instance, in the burgeoning field of hedonic (wellbeing) psychology (e.g., Kahneman, Diener, & Schwarz, 1999); or of the growing body of evidence on how clients contribute towards psychological change (Bohart & Tallman, 1999)? Developing our work as facilitators of psychological wellbeing could lead us to draw on a much wider body of psychological knowledge as the basis for our profession.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this paper has been to develop a vision of what counselling psychology might be if we strove to actualise the humanistic values that, for many of us, are its core. The picture that emerges is of a profession that strives to help individuals and communities develop their potentiality and wellbeing through responsive, empowering, deeply respectful ways of relating. It is also of a profession that takes an active lead in finding out more about how this can be achieved: researching, and drawing together, a psychological body of knowledge that can help people maximise satisfaction and fulfilment in their lives.

Does this vision bear any reality to the actual, concrete practice of counselling psychologists today? Certainly, it is idealistic, and there is no doubt, as Peter Martin (2006) writes, that such changes will not be easy to bring about. However, there is no rush and, as Moscovici and colleagues (1969) have demonstrated, minorities can have considerable impact if they remain consistent and unwavering in their intent. For counselling psychologists working in IAPT and other NHS settings, trans-diagnostic and highly responsive practices may be discouraged; but the essence of a deeply humanising and welcoming stance towards clients can always be carried through. Moreover, there is clear evidence within health and policy circles of a move towards a more potentiality- and recovery-based understanding of psychological functioning. This is something that counselling psychologists should not only be feeling encouraged by; but should be taking an active lead in championing and contributing towards. As those of us from an existential perspective would argue, there is no set future: as counselling psychologists, we can choose to try and create a more welcoming future for our clients, or we can choose to wait and hope it will happen. The one thing we cannot choose is not to choose!

Finally, what are the implications of this analysis in terms of a merger with clinical psychology? For those who are committed to the humanistic ethic outlined in this paper, the issue is probably much more the survival and the promotion of this particular set of values, than with the survival and promotion of counselling psychology, per se. As Walsh and Frankland (2009) point out, other professions may be moving in a more humanistic direction and, were clinical psychology to put a welcoming of the Other at its core, I would see no reason for counselling psychology to maintain a separate identity. But if merger means merger into a pathology-orientated, thingifying psychology, it would seem essential that some branch of psychology is maintained which works with clients from a humanising stance. Perhaps, then, as Walsh and Frankland (2009) suggest, the field of counselling psychology will split, with those prioritising humanistic values remaining a small, but potentially vocal, force within psychology; and those with a more strictly clinical interest merging with the wider applied psychology field. Whatever happens, though, that voice for humanisation and for welcoming the Other will always have a critical role to play in the psychological field, calling us back from tendencies that are virtually intrinsic to the psychological project – thematisation and it-ification of human experiencing – and reminding us that nurturing, and treasuring, the uniqueness, diversity and otherness of clients must always remain central to our work.

REFERENCES

Anonymous. (2009). Counselling Psychology and the next 10 years: Some questions and answers. Counselling Psychology Review, 24(1), 34.

Bohart, A. C., & Tallman, K. (1999). How Clients Make Therapy Work: The Process of Active Self-Healing. Washington: American Psychological Association.

British Psychological Society Qualifications Office. (2008). Qualification in Counselling Psychology: Candidate Handbook. Leicester: British Psychological Society.

Buber, M. (1958). I and Thou (R. G. Smith, Trans. 2nd ed.). Edinburgh: T & T Clark Ltd.

Cohen, R. A. (2002). Maternal Psyche. In E. E. Gantt & R. N. Williams (Eds.), Psychology for the Other: Levinas, Ethics and the Practice of Psychology (pp. 32-64). Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Cooper, M. (2003). Existential Therapies. London: Sage.

Cooper, M. (2007). Humanizing psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 37(1), 11-16.

Cooper, M. (2008a). Essential Research Findings in Counselling and Psychotherapy: The Facts are Friendly. London: Sage.

Cooper, M. (2008b). Existential psychotherapy. In J. LeBow (Ed.), Twenty-First Century Psychotherapies: Contemporary Approaches to Theory and Practice (pp. 237-276). London: Wiley.

Cooper, M. (2009). Foreword. In T. Bond (Ed.), Standards and Ethics in Counselling in Action. London: Sage.

Cooper, M., & Hermans, H. (2007). Honouring Self-otherness: Alterity and the Intrapersonal. In L. M. Simão & J. Valsiner (Eds.), Otherness in Question: Labyrinths of the Self (pp. 305-315). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Cooper, M., & McLeod, J. (2007). A pluralistic framework for counselling and psychotherapy: Implications for research. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 7(3), 135-143.

Cowie, H. (2000). Peer support against bullying. Counselling Psychology Review, 15(4), 8-12.

Davis, C. (1996). Levinas: An Introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press.

den Boer, P., Wiersma, D., & van den Bosch, R. J. (2004). Why is self-help neglected in the treatment of emotional disorders? A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 34(6), 959-971.

Fischer, C. T. (1970). The testee as co-evaluator. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 17(1), 70-76.

Foresight Mental Capital and Wellbeing Project. (2008). Final Project report – Executive summary. London: The Government Office for Science.

Galbraith, V. E., & Galbraith, N. D. (2008). Should we be doing more to reduce stigma. Counselling Psychology Review, 23(4), 53-61.

Giddings, D. (2009). Counselling Psychology and the next 10 years: Some questions and answers. Counselling Psychology Review, 24(1), 10.

Gillon, E. (2007). Person-centred Counselling Psychology: An Introduction. London: Sage.

Goldstein, R. (2009). The future of Counselling Psychology: A view from the inside. Counselling Psychology Review, 24(1), 35-37.

Gurman, A. S. (1977). The patient's perception of the therapeutic relationship. In A. S. Gurman & R. A. M (Eds.), Effective Psychotherapy: A Handbook of Research (pp. 503-543). New York: Pergamon Press.

Joseph, S. (2008). Psychotherapy's inescapable assumptions about human nature. Counselling Psychology Review, 23(1), 34-40.

Journal of Humanistic Psychology. (2009). Five basic postulates of humanistic psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 49(1), 3.

Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. (Eds.). (1999). Well-being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kanellakis, P. (2009). Counselling Psychology and the next 10 years: Some questions and answers. Counselling Psychology Review, 24(1), 22.

Kinderman, P. (2009). The future of Counselling Psychology. Counselling Psychology Review, 24(1), 16-21.

King, M., Sibbald, B., Ward, E., Bower, P., Lloyd, M., Gabbay, M., et al. (2000). Randomised controlled trial of non-directive counselling, cognitive-behaviour therapy and usual general practitioner care in the management of depression as well as mixed anxiety and depression in primary care. Health Technology Assessment, 4(19).

Koehn, D. (1994). The ground of professional ethics. London: Routledge.

Laing, R. D., & Esterson, A. (1964). Sanity, Madness and the Family. London: Penguin Books.

Levinas, E. (1969). Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority (A. Lingis, Trans.). Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Levinas, E. (2003). Humanism of the Other (N. Poller, Trans.). Chicago: University of Illinois.

Martin, P. (2006). Different, dynamic and determined: The powerful force of Counselling Psychology in the helping professions. Counselling Psychology Review, 21(3), 34-37.

Miller, G. A. (1969). Psychology as a means of promoting human welfare. American Psychologist, 24, 1063-1075.

Milton, M., Charles, L., Judd, D., O'Brien, M., Tipney, A., & Turner, A. (2002). The existential-phenomenological paradigm: the importance for psychotherapy integration. Counselling Psychology Review, 17(2), 4-20.

Moscovici, S., Lage, E., & Naffrenchoux, M. (1969). Influences of a consistent minority on the responses of a majority in a colour perception task. Sociometry, 32, 365-380.

National Institute for Mental Health in England. (2005). NIMHE Guiding Statement on Recovery. London: Department of Health.

Nelson-Jones, R. (2002). Essential Counselling and Therapy Skills: The Skilled Client Model London: Sage.

Nelson-Jones, R. (2003). Skilling the client: An important concept for counselling psychologists. Counselling Psychology Review, 18(2), 3-11.

Orlans, V., & Van Scoyoc, S. (2008). A Short Introduction to Counselling Psychology. London: Sage.

Pilling, S. (2008). NICE Guidance. Therapy Today, 19(9), 12-16.

Rowan, J. (2001). Counselling psychology and research. Counselling Psychology Review, 16(1), 7-8.

Segrin, C. (2001). Interpersonal Processes in Psychological Problems. New York: Guilford.

Sequeira, H., & Van Scoyoc, S. (2001). Division round table 2001: Should counselling psychologists oppose the use of DSM-IV and testing? Counselling Psychology Review, 16(4).

Snyder, C. R., Michael, S. T., & Cheavens, J. S. (1999). Hope as a foundation of common factors, placebos, and expectancies. In M. Hubble, B. L. Duncan & S. D. Miller (Eds.), The Heart and Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy (pp. 179-200). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Spinelli, E. (2001). Counselling psychology: A hestitant hybrid or a tantalising innovation? Counselling Psychology Review, 16(3), 3-12.

Stiles, W. B., Honos-Webb, L., & Surko, M. (1998). Responsiveness in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice, 5(4), 439-458.

Stuart, S., & Robertson, M. (2003). Interpersonal Psychotherapy: A Clinician's Guide. London: Arnold.

Thatcher, M., & Manktelow, K. (2007). The cost of individualism. Counselling Psychology Review, 27(4), 31-43.

Timulak, L. (2008). Significant events in psychotherapy: An update of research findings. Paper presented at the ScotCon/SPR Seminars, Glasgow.

Tryon, G. S., Blackwell, S. C., & Hammel, E. F. (2007). A meta-analytic examination of client-therapist perspectives of the working alliance. Psychotherapy Research, 17(6), 629-642.

Turpin, G. (2009). The future world of psychological therapies: Implications for counselling and clinical psychologists. Counselling Psychology Review, 24(1), 23-33.

Walsh, Y. (2003). Testing the way the wind blows: Innovation and a sound theoretical base. Counselling Psychology Review, 18(3), 29-34.

Walsh, Y., & Frankland, A. (2009). The next 10 years: Some reflections on earlier predictions for Counselling Psychology. Counselling Psychology Review, 24(1), 38-43.

Woolfe, R. (1996). The nature of counselling psychology. In R. Woolfe, W. Dryden & S. Strawbridge (Eds.), Handbook of Counselling Psychology (2nd ed., pp. 3-20). London: Sage.